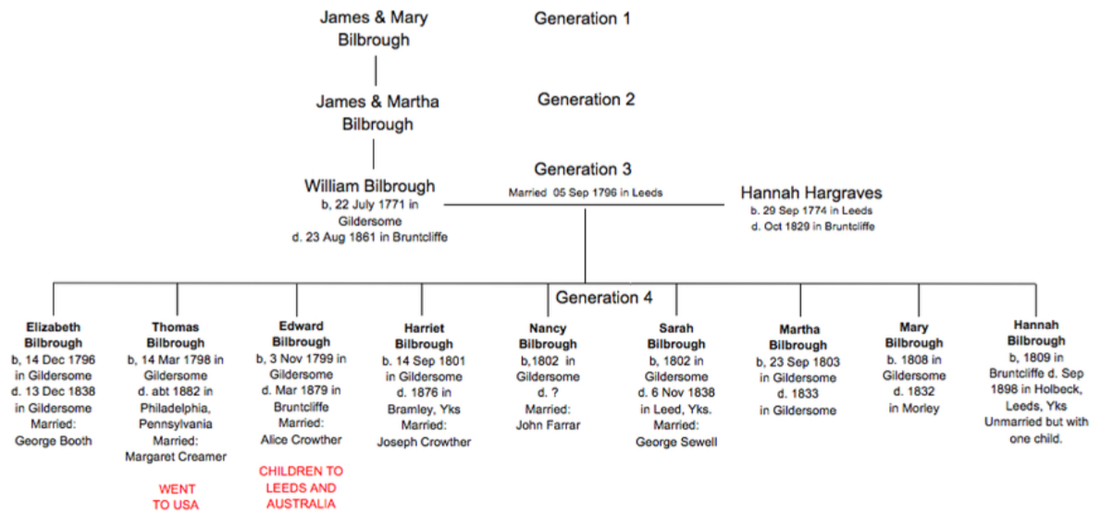

The Bilbrough Family of Gildersome and Bruntcliffe

William Bilbrough, born 1771 and his wife Hannah Hargreaves, born 1774

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

NOTE: Unless otherwise cited, all quotes on this page are from the diaries and journals of William Booth Bilbrough, grandson of William and Hannah Bilbrough. Graciously provided by his great grand-daughter, Judith Burton nee Bilbrough. I have taken the liberty of slightly editing the content when needed.

“My grandfather’s brothers lived, one at Harthill House, one at Park House, one at Turton Hall and my Grandfather at Bruntcliffe. He was manager for his brother John in the malt kilns and on the farm. Mary Cooper, my Grandfather’s youngest sister, left him one hundred pounds which came in very nicely and paid for his cow being kept for a long time as his brother allowed him interest upon it. When his brother died, Mr. Alfred took it on and it was just exhausted when my Grandfather died. He was a grand man and I was his favorite Grandson. I have worked on the farm with him, in the garden, journeyed with him in search of barley sacks and walked (with him) through Morley Tunnel before it was opened for traffic. I have helped him dig and hoe and mend fences, clean the land of wicks and burn them. Mr. John Bilbrough praised me as a shearer of corn. My Grandfather was loved, honored and respected by all who were thoroughly in touch with him. All John’s sons looked after his tobacco, even William Radford Bilbrough would occasionally empty his tobacco pouch into Grandfather’s iron tobacco box. ........”

Below are the actual cottages, at least partially built by William Bilbrough in the 1820’s or 30’s. Called “the Old Thatched Cottage”, William lived here for thirty years or so and with him lived his youngest daughter, Hannah, and grandson William Booth Bilbrough. The photo is taken from William Smith’s book, “Morley, Ancient and Modern”

By William Radford Bilbrough from his “Chronices”:

“William, eldest son of the above James Bilbrough and uncle to my father, was brought up to the cloth trade but did not stick to it. He lived at Bruntcliffe and was employed by his brother John in his malt-kilns. He was married and his wife afterwards lost her senses and was confined in an asylum (1823 – 29). His hair never lost its’ colour but he had a nice head of brown hair when he died. On his 90th birthday he went to see his daughter Harriet, then Mrs. Jos. Crowther who lived in Gildersome St., this was his last visit. His daughter Harriet’s husband’s funeral was preached and published by Rev. J. Haslam as a tract. He was buried in Morley Chapel yard in the same grave as his father. Edward his 2nd son lived at Bruntcliffe . Thomas, the eldest, went to America in 1821, there he married (he visited this country in 1874). His youngest daughter lived with her father in the old straw thatched farm house, with very small windows, till his death.”

As the eldest child of James and Martha, to William fell the disagreeable task of nanny to sisters Hannah, Sarah and brother John. The household demands and financial situation left his mother with little choice. Eventually the task passed to his sister Hannah. It was then decided that William would be sent to a clothier in Birstall to become an apprentice in the cloth trade. William had an aunt who married a clothier of Birstall named Stockwell and it was probably with him to whom he was apprenticed. The experience was not a happy one.

"I have heard my Grandfather say that they used to starve their apprentices. They had to eat, at the same time as their master and no longer, and his wife prudently cooled her husband’s food before calling him to the meal, while she carefully placed before the apprentices food brought up to as near 212 degrees as she knew how to make it, so you can imagine the difference in dispatch. “David Copperfield and his keeper” would furnish but a poor illustration. Grandfather also spoke of a good serving woman who always put a nice quantity of currants into the yorkshire pudding in a particular place. This came under the observation of one of the apprentices who perceived the Lady of the House always secured the prize. So, one day he turned round the pudding tin and met his reward, and the disappointed Lady said, “where are my currants?” ............ He (William) was noted for being a strong person, when 18 years of age, he could get a twenty stone bag of flour upon his back and carry it up three flights of stairs, a thing none of the other apprentices could do. Now I suppose not living far from Gildersome, he would see his parents and they would be glad to see their well developed son. Upon one of those occasions, perhaps near Christmas, when sliding or skating upon Mr. Turton’s dam, and at the time I refer to it was very deep, the ice broke and let him in but he manager to prevent himself from getting under the ice. When one piece broke off, he took hold of that in advance and kept his head out till a rope was procured, and that rope he always maintained was the means of his salvation.”

Right: In this 1830’s map portion, circled in red: in Gildersome, is Harthill House and Sharp’s House, and in Bruntcliffe is “Bilbrough’s Corner”.

As James and Martha Bilbrough’s fortunes improved, so diminished the need to send their sons away to learn a trade. Instead, they were sent to the new Quaker school over the rise of Hart Hill and less than ten minutes walking distance from home. There, Quaker Ellis provided a quality and practical education, the kind that added polish and the persona of the gentleman professional to the Bilbrough brothers. William missed out on most of this defining education. That he could read and write, I have no doubt. It has been suggested by William Radford Bilbrough that William was slow and lazy, but I don’t believe this is so, his siblings, nieces and nephews always held him in the highest and warmest regard. William seemed to prefer an out of doors and vigorous life and may have lacked the temperament necessary to remain slumped over a dimly lit desk, writing bills, receipts and doing sums.

I’m certain that William was expected to take over the family’s clothier business and impart what he had learned to his brothers. In Yorkshire, times were tough for those in the wool trade. In the eighteenth century, the wool business had relied increasingly upon foreign markets but the War for American Independence, the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic Wars produced a boom and bust economy and bankruptcies were common. Gildersome and vicinity was not immune and neither were the Bilbroughs.

“His father appears to have required his services, what with the malt kiln, Public House and farm. Plenty of work could be found for him and as cloth making was not in so flourishing a condition at that particular time, and his father did not feel disposed to lend William even a small capital in a hazardous enterprise which offered only slow returns, he favoured the alternative of employing his athletic son at other tasks.”

To think that William had no degree of success as a clothier would not be accurate. In most of the Batley Parish records for the birth of his children, he is listed as a clothier. He probably maintained that profession until he moved to Bruntcliffe in 1808 when his son’s Thomas and Edward began to take over. Some of his success can be judged by the following, written by Philip Henry Booth in his “History of Gildersome”, it demonstrates that William had money to invest in a health insurance plan. “In the year 1798 a Sick Club was formed in the Township, to which Members contributed quarterly, and from the funds of which allowances were made to members in case of sickness, and to widows or representatives in case of death. The Society was flourishing at one time and had accumulated funds to the extent of ₤1,200, but as other Clubs were started, and young men ceased to enter, it was ultimately wound up about the year 1854. On the first page of the book I find the following members enrolled: ................

.............. 1789 Oct. 17th Bilbrough, William aged 26 Clothier..........”

“Now, when he had finished his apprenticeship, he saw and admired a soldier’s daughter of the name of Hargraves. How it all came about I am unable to describe. His apprenticeship must have been completed some four years before this period. William and wife moved into the house of small dimensions and situate near to the bottom of the avenue leading up to Harthill House, on the left hand side. At the time of this writing, 1906, it must have been demolished more than 40 years, he entered that house in 1795.”

As a clothier he probably traveled to Leeds on some market days to sell his wares. It must have been on one of these trips that William met Hannah Hargraves (or Hargreaves), whose father may have operated a booth at one of the “cloth halls”. Best indications are that Hannah was Hannah Robinson Hargreaves b. 29 Sep 1774 in Holbeck, a district of Leeds. And that her parents were Joshua Hargreaves and Mary Askee. They were married in September of 1796 in Leeds, in order to be close to the bride’s family, but the happy couple decided to live at Sharp House adjacent to his parent’s Harthill House. Their first child, Elizabeth, was born there two months later (in those days, couples were often married when the bride was pregnanant). The couple continued to live in Gildersome where they had seven more children, many of which seem to have been named after Hannah’s brothers and sisters.

“John Wheater took Hannah’s sister, Sarah, for his wife, he resided I think at New Wortley but at that period the fields hardly knew a house. My Grandfather’s brother-in-law Wheater always used to speak of Hargraves the manufacturer as his cousin, lately the firm has been known as “Hargraves and Nussey” of Low Wortley. John Wheater often came to our house and he would recount the acts of his brother, Willie, who was for a time with Pablo’s, that famous circus which often visited Leeds, thus connected, he would often get in free. Willie used to be advertised in papers and placard upon the walls as “Willie Wheater the Yorkshire Leaper”

As the years passed at Harthill House, James Bilbrough’s sons took over more of his operations. John, took over the farming and malting probably with help from James. William ran the cloth making processes with Joseph and Samuel, first as apprentices and then as assistants. When their father died in 1805, the Bilbrough brothers continued to stick together and maintained their prior arrangements. James’ Will left all property and money to his wife, Martha, and it appears that she invested money in her son’s various business schemes. Deeds and documents indicate that William, James and John, as partners, were buying and some properties in Gildersome to enlarge the farming business. While Joseph and Samuel had dreams of exporting cloth to the now prosperous American markets and eventually took over the clothing business.

Right, circa 1900, the “Old Stone Cottage” later called Rose Cottage is on the left. The attached buildings left of that is the Angel Inn. The tall building behind is Bruntcliffe Mill sitting on the location of Plantation House and the Maltkiln Yard. Picture courtesy of the Morley Archives

In 1808, William and Hannah’s family had grown to six children with another on the way. Though the youngest four girls were able to double up, the small Sharp’s House could no longer hold such a large family. The decision was made to move to Bruntcliffe and into the Bilbrough’s ancestral home, the “Old Stone Cottage”, built by William’s grandfather around 1740. Their mother, Martha, held the leasehold to the cottage and at the time of her husband’s death it was occupied by a tenant who, I believe, moved out in 1808. That corner of Bruntcliffe I call “Bilbrough’s Corner”. William’s Uncle and Aunt, John and Elizabeth Bilbrough, lived with Benjamin and Martha Mitchell at the Mitchell House (see map), Martha was their daughter. The Mitchells carried on the Cloth Dressing business of the elder John Bilbrough. The Angel Inn, built by William’s Uncle John circa 1780, was run and occupied by Thomas and Ann Helliwell, Ann was another of Uncle John’s daughters. And the fields behind the Mitchell House were owned by Joseph Asquith, one of William’s uncles.

BRUNTCLIFFE CROSSROADS CIRCA 1814 (left)

made for Lord Dartmouth Map courtesy of the Morley Archives 1. Helliwell’s Angel Inn. and “Old Stone Cottage

2. The Mitchell House

3. (red circle) Lister’s Prospect House & Property.

4. Location of the “Old Thatched Cottage”

5. Helliwell’s Brewhouse

6. Plot, recently purchased by John Bilbrough.

7. Shoulder of Mutton Inn, still in business today.

8. Darthmouth’s Quarry9. Parcels for sale, “New Morley Enclosure Act”

A few years later, in 1813, his brother John married Elizabeth Priestley and received a large dowery and annuity, John was ready to invest. John and William, as partners leased the eight acre Lister parcel behind the Angel Inn (see map), described in the deed of lease as, “Dwelling House with the Maltkiln Barn Stable Pigeon Cote and Summer House and other Out Buildings Garden Orchard and Appurtenances”. Immediately after their marriage, John and his bride moved into Prospect House, behind Rose Cottage. John continued to purchase and lease more property in Bruntcliffe until eventually the size of his acreage totaled 35 to 40 acres. William was a partner in the Lister parcel but whether he had a share in any of the others is not known. John, without William, also purchased more land in Gildersome. The years that followed, up to the early 1820’s was an expansion period for the Malting business. Enlisting William’s sons, Thomas and Edward, they built a second malt kiln in Gildersome, attached to Harthill House and a second one at Listers. 1814 saw the birth of Joseph Brooks Bilbrough, son to John and Elizabeth at Plantation House. Elizabeth Priestley Bilbrough did not care for life at Bruntcliffe and longed to be closer to her sister at Gildersome, Ellen Bilbrough who married James. They packed up and moved into Sharp’s house where William and family had lived a few years prior. John, with his newly gotten wealth was now clearly in charge of their farming and malting business and worked out an agreement whereby William would manage operations at Bruntcliffe and John would do the same at Gildersome.

Life at Bruntcliffe between 1808 and 1822 was good. William and Hannah’s last child, Hannah Bilbrough was born in Rose Cottage. William oversaw the expansion of his business, that included the new farmland and extra Kiln. He directed the malt production and kept up his clothier business during the colder months and saw to the crop yield during the planting and harvesting months. He did not lack for a labor force, by 1820, the extended Bilbrough family living at the corner, including Helliwells and Mitchells, totaled over 25 souls. His sons, Thomas and Edward, helped in all aspects of William’s endeavors but seemed particularly interested in cloth manufacturing and had dreams of becoming wool merchants and exporters. They put together a shipment of woolen blankets and Thomas, in 1821, followed it to Philadelphia. There, he lived for a time with his first cousin once removed, John Bilbrough, son of William’s Uncle John. Edward sent a few more shipments to Thomas but the venture fizzled out. Edward remained in Bruntcliffe as a cloth maker but Thomas never saw his parents again. During this same period, daughters Elizabeth and Harriet went to live at Gildersome as housekeepers to their grandmother, Martha, and nannies to the children of Aunt Elizabeth.

Hannah, William’s wife, developed a high fever for some length of time and after the fever broke, she was described as, “...physically and mentally incapacitated...”. It fell to the youngest daughter, Hannah, to look after and nurse her poor mother. Around 1823, she became too ill for home care and required institutionalization at a hospital in Wakefield. The financial burden of Hannah’s debility must have been terrific and caused William to spend down most of what he had saved. He sold out his percentage in the partnerships he had with his brothers, mostly John. He still remained as manager at Bruntcliffe but as a salaried employee. His mother had died in 1827 and her estate was divided between her children into equal shares. William received the leasehold to Rose Cottage but any other property or money seems to have been used up for the care of Hannah. Two years later, Hannah died.

The same period saw the marriages of Edward, Elizabeth, Harriet, Nancy and Sarah. The daughters moved in with their husbands but Edward remained in Bruntcliffe. When Edward married, William left Rose Cottage to the him and his wife and moved into the “Old Thatched Cottage” across the street from the Angel (see map of Bruntcliffe). John had leased this corner of the intersection from Lord Dartmouth and it contained a small cottage that probably was a portion of the Old Thorn Inn. When looking at the photo of the “Old Thatched Cottage” above, one can see that it was composed of two separate units, like a duplex. William, nearing 60 years, added on to the small cottage, probably about 1830, and moved in with his daughter Hannah. They both lived at this cottage until William’s death in 1861. In the book, “Morley, Ancient and Modern”, author William Smith devotes quite a bit of a chapter describing this very cottage and what life was like in it fifty years prior to his writing (about 1880). The Chapter starts with a full page photo of the “Old Thatched Cottage” that can be seen at the top of this page. The sketch above is also from the same chapter and depicts the interior of how the cottage may have appeared, one can easily imagine daughter Hannah ironing at the table. Smith also makes the following observation, when referring to walking down the Bradford/Wakefield Rd. just after the Angel Inn, “Sauntering along the “Street’ in the direction of Stump Cross, we have on our left the residences of the Bilbroughs, the Crowthers and the Mitchells, whose ancestors have nestled here for more generations than we dare guess at”.

A double tragedy visited the Thatched Cottage in and about 1832 and 1833. Daughter Mary was a servant to a physician in Leeds when she became ill and had to leave for home. Hannah, her sister, nursed her at that time. Then, sister Martha, who worked as servant to two “maiden”sisters, was about to depart for London, with them, when she first visited her sick sister at Bruntcliffe. There, she contracted the same illness and became bedridden also. Hannah cared for them both but in August of 1832, Mary died and Martha lingered until May of 1833. Around the same time, Yorkshire was ravaged by a cholera epidemic, daughters Mary and Martha appear to have been its victim.

Hannah led a life of service. When 10 to 12 years of age, she lived at Harthill House as servant to her grandmother, Martha Bilbrough. As a teenager at Rose Cottage in Bruntcliffe, she nursed her sick mother. Then at the Thatched Cottage, she nursed her dying sisters and provided for her father’s needs for almost another thirty years. Her sister Elizabeth (Betty), who was married to George Booth and living in Gildersome, fell ill in 1838. Hannah went to nurse her and help with the families five children. Betty died in December of that year and Hannah remained to continue her help to the family. While there, she fell in love with James Booth, George’s brother. The couple agreed to marry but James fell ill and was not expected to live. Hannah discovered she was bearing James’ child and when she could not hide the fact any longer she told her father. On May 30, 1839, Hannah bore a son, she named him William. James Booth recovered after the birth but it was decided that Hannah should remain unmarried. Her son, William Bilbrough, is the same William “Booth” Bilbrough that wrote the journals and dairies that I have used as a source for these pages. The middle name, Booth, I have given to him to help in identifying him from all the other William Bilbroughs, the most popular name in the Bilbrough family. William Booth lived with his grandfather for 22 years.

Left: William Booth Bilbrough courtesy of his great-great granddaughter, Judith Burton nee Bilbrough. Again, William Booth Bilbrough:

"My grandfather left the little house where he led his loving wife and in 1808, went to reside in Bruntcliffe in a more commodious house. His brother John appears to have been the principle director of the business. At that time, my Grandfather was to receive for his services, 21 shillings per week to be rent free and to have a cow kept. These were, at the time, considered to be good terms. My Grandfather looked after the farm that was rented of Lord Dartmouth consisting of eight fields, five of them were pasture lands, and the three lower down were used for growing oats, wheat, turnips and Potatoes. In those fields I have spent thousands of hours. I am of the opinion that John Bilbrough perhaps rented the malt kilns of the company and afterwards bought them. If that be so, another farm of about the same size would have to be added to the one I have before described, making a farm of about 80 acres in the malt making process. There were two cisterns in which to steep the barley, two low floors and two drying kilns, a large one and a small one, one with four fires and one with 2 fires. I will describe some of the particulars respecting the large Drying Kiln. Cinders were used of good quality, the furnaces were arched over on each side of the respective fires and the further end from the stoker, there were apertures, 4 on each side and 2 at the end of each of the fires, in order that the heat might radiate in uniformity underneath the perforated plates or tiles upon which the Baptizes Barley, after being three days in the crock, and made a pilgrimage of about 12 stages along the lower ?????? floor, it was pitched by a large wooden shovel into the “torrid zone” and after having taken into its constitution a certain defined quantity of heat, it assumes another name, that of Malt. These remarks are for the uninitiated. My Grandfather once took me to see this larger Drying Place when I was about 5 years old but there were but two fires that I could see, but to our right there was a dark passage, my guardian invited me to follow him which I did. This was to me unexplored geography, having traveled the passage, I found to my surprise, it led to another stoke room, but more comfortable and more retired with arched roof from which there was suspended a lamp to defuse the light. Its fires looked red and inviting and immediately in front and on one side were two seats fixed, here it did seem to me to be a rallying place to spend a few quite hours when the labours of the day were finished and the stoker would be glad of their company and conversation. Perhaps here, Mr. John, the Master and my grandfather, would discuss every conceivable subject relating to the customers, the malt process, the farm, and the cattle.

Customers would try to keep on courteous terms with my Grandsire for he kept the key of the beer cellar in the large house in which I believe John Bilbrough resided for a short time, but his wife I think did not care for Bruntcliffe but wished to be down in Gildersome near to her sister. Now the Beer Cellar approached from the outside, and no doubt they would occasionally get round my Grandfather, who was good natured, and get some of the special Beer. This beer was brewed mainly for customers who came for Malt, as kind of a recommendation, it was made very good, it was not such as they sell in public houses now. My mother used to brew 3 strokes and 1 peck, that was the malt used, and she did not make a large quantity, so you will see it was a treat to those who liked beer."

Left: Bruntcliffe from an 1854 Army Survey

"Let me tell the story of the good dog Peroe. This dog had an excellent reputation, good, kind, quiet but with respect to rats, he knew what was expected of him and he courageously did his duty. I have heard my Grandfather speak of his achievements and I will recount one of his performances; in one of the cisterns when empty of water there were 4 big rats looking out, I suppose, for any barley that might be left. Peroe’s attention was drawn to the scene of operation with alacrity, he did jump in amongst them, pick them up and shake them and break the backbone of each of them, and then he got upon the edge of the cistern, looked at my Grandfather, and if he had known the English language and could have spoken, perhaps he would have said, “That’s the way to polish them off”, and if he got a few pats upon the back and a tender stroke of the head, he considered himself amply rewarded. We must admit that to attack the rats, he put himself into some danger, for rats when they are pinned will combine and make common cause against the enemy. What is wanted in a dog for this work is courage, precision and dispatch. Those who read these writings of mine will observe that I have made a digression, but still some very valuable information has been rendered."

When William’s grandson wrote above, about visiting the malt kilns when he was 5 years old, William was 73. His brother John was 62 at the same time, and was retiring from his malt and farming operations. John groomed his son Alfred to take over, who was in his early 20’s and more active. During the 1840’s John sold about half of his holdings in Bruntcliffe but retained the leaseholds to the malt yard and the farm across Bruntcliffe Lane including the Old Thatched Cottage where William resided. William Radford Bilbrough, writing about 1900, stated that when John, died in 1850, Alfred continued the lease of the farm and thatched cottage, at a loss, just to provide William with a place to live. Alfred gave up the lease to the malt yard and soon Prospect Mills was erected on the spot, operated by Thomas Stephenson. Prospect Mill later became known as Bruntcliffe Mill and can be seen in the photo above behind the Old Angel Inn. Again from “Morley, Ancient and Modern”, “Prospect Mill, Bruntcliffe, stands on the site of the extensive malt-kilns, formerly in the occupation of the Bilboroughs, a name like Crowther, indigenous to Bruntcliffe. The kilns were converted into a woolen mill about thirty years ago.”

William was also looked after in the Wills of many of his brothers and sisters and so was able to maintain a comfortable life until the end. In the 1841 census, William, aged 70, was living with Hannah, her son William (2 yrs old) and grandson Thomas, Edward’s son; William’s occupation is noted as “Maltster”. The 1851 census finds 80 year old William, a “Retired Maltster”, occupying the same home with daughter Hannah and her son William. 1861. At age 90, the census that year, lists William as “Farmer”, Hannah and William are again co-occupants. A few months after the 1861 census recorded his presence, William died, he was 90 years old. he had lived at least 30 years at the “Old Thatched Cottage”, sharing it at times with his unwed daughters and various grandchildren. His daughter Hannah remained to care for him as he aged.

Above is the registered death entry for William. The “James Bilbrough in attendance” was William’s grandson James born 1838, he was Edward’s son.

William Radford Bilbrough, wrote this in his diary:

“Feb. 13 1858 This afternoon Pa & I went to Morley by train and walked to Bruntcliff and saw Old Uncle William and looked round the garden.” “Aug 22, 1861 Thr. Old Uncle William died aged 90.”

After William’s death, Alfred gave up the leasehold to the farm and cottage to the Helliwells. Hannah and her son William were invited to move into the old part of Harthill House in Gildersome and remained there for some time. Edward, having some success in the cloth business, purchased Rose Cottage from Lord Dartmouth. His descendants continued to live there until about 1905, it was torn down in the 1960’s after about 200 years of occupation by the Bilbroughs.

NOTE: Unless otherwise cited, all quotes on this page are from the diaries and journals of William Booth Bilbrough, grandson of William and Hannah Bilbrough. Graciously provided by his great grand-daughter, Judith Burton nee Bilbrough. I have taken the liberty of slightly editing the content when needed.

“My grandfather’s brothers lived, one at Harthill House, one at Park House, one at Turton Hall and my Grandfather at Bruntcliffe. He was manager for his brother John in the malt kilns and on the farm. Mary Cooper, my Grandfather’s youngest sister, left him one hundred pounds which came in very nicely and paid for his cow being kept for a long time as his brother allowed him interest upon it. When his brother died, Mr. Alfred took it on and it was just exhausted when my Grandfather died. He was a grand man and I was his favorite Grandson. I have worked on the farm with him, in the garden, journeyed with him in search of barley sacks and walked (with him) through Morley Tunnel before it was opened for traffic. I have helped him dig and hoe and mend fences, clean the land of wicks and burn them. Mr. John Bilbrough praised me as a shearer of corn. My Grandfather was loved, honored and respected by all who were thoroughly in touch with him. All John’s sons looked after his tobacco, even William Radford Bilbrough would occasionally empty his tobacco pouch into Grandfather’s iron tobacco box. ........”

Below are the actual cottages, at least partially built by William Bilbrough in the 1820’s or 30’s. Called “the Old Thatched Cottage”, William lived here for thirty years or so and with him lived his youngest daughter, Hannah, and grandson William Booth Bilbrough. The photo is taken from William Smith’s book, “Morley, Ancient and Modern”

By William Radford Bilbrough from his “Chronices”:

“William, eldest son of the above James Bilbrough and uncle to my father, was brought up to the cloth trade but did not stick to it. He lived at Bruntcliffe and was employed by his brother John in his malt-kilns. He was married and his wife afterwards lost her senses and was confined in an asylum (1823 – 29). His hair never lost its’ colour but he had a nice head of brown hair when he died. On his 90th birthday he went to see his daughter Harriet, then Mrs. Jos. Crowther who lived in Gildersome St., this was his last visit. His daughter Harriet’s husband’s funeral was preached and published by Rev. J. Haslam as a tract. He was buried in Morley Chapel yard in the same grave as his father. Edward his 2nd son lived at Bruntcliffe . Thomas, the eldest, went to America in 1821, there he married (he visited this country in 1874). His youngest daughter lived with her father in the old straw thatched farm house, with very small windows, till his death.”

As the eldest child of James and Martha, to William fell the disagreeable task of nanny to sisters Hannah, Sarah and brother John. The household demands and financial situation left his mother with little choice. Eventually the task passed to his sister Hannah. It was then decided that William would be sent to a clothier in Birstall to become an apprentice in the cloth trade. William had an aunt who married a clothier of Birstall named Stockwell and it was probably with him to whom he was apprenticed. The experience was not a happy one.

"I have heard my Grandfather say that they used to starve their apprentices. They had to eat, at the same time as their master and no longer, and his wife prudently cooled her husband’s food before calling him to the meal, while she carefully placed before the apprentices food brought up to as near 212 degrees as she knew how to make it, so you can imagine the difference in dispatch. “David Copperfield and his keeper” would furnish but a poor illustration. Grandfather also spoke of a good serving woman who always put a nice quantity of currants into the yorkshire pudding in a particular place. This came under the observation of one of the apprentices who perceived the Lady of the House always secured the prize. So, one day he turned round the pudding tin and met his reward, and the disappointed Lady said, “where are my currants?” ............ He (William) was noted for being a strong person, when 18 years of age, he could get a twenty stone bag of flour upon his back and carry it up three flights of stairs, a thing none of the other apprentices could do. Now I suppose not living far from Gildersome, he would see his parents and they would be glad to see their well developed son. Upon one of those occasions, perhaps near Christmas, when sliding or skating upon Mr. Turton’s dam, and at the time I refer to it was very deep, the ice broke and let him in but he manager to prevent himself from getting under the ice. When one piece broke off, he took hold of that in advance and kept his head out till a rope was procured, and that rope he always maintained was the means of his salvation.”

Right: In this 1830’s map portion, circled in red: in Gildersome, is Harthill House and Sharp’s House, and in Bruntcliffe is “Bilbrough’s Corner”.

As James and Martha Bilbrough’s fortunes improved, so diminished the need to send their sons away to learn a trade. Instead, they were sent to the new Quaker school over the rise of Hart Hill and less than ten minutes walking distance from home. There, Quaker Ellis provided a quality and practical education, the kind that added polish and the persona of the gentleman professional to the Bilbrough brothers. William missed out on most of this defining education. That he could read and write, I have no doubt. It has been suggested by William Radford Bilbrough that William was slow and lazy, but I don’t believe this is so, his siblings, nieces and nephews always held him in the highest and warmest regard. William seemed to prefer an out of doors and vigorous life and may have lacked the temperament necessary to remain slumped over a dimly lit desk, writing bills, receipts and doing sums.

I’m certain that William was expected to take over the family’s clothier business and impart what he had learned to his brothers. In Yorkshire, times were tough for those in the wool trade. In the eighteenth century, the wool business had relied increasingly upon foreign markets but the War for American Independence, the French Revolution and subsequent Napoleonic Wars produced a boom and bust economy and bankruptcies were common. Gildersome and vicinity was not immune and neither were the Bilbroughs.

“His father appears to have required his services, what with the malt kiln, Public House and farm. Plenty of work could be found for him and as cloth making was not in so flourishing a condition at that particular time, and his father did not feel disposed to lend William even a small capital in a hazardous enterprise which offered only slow returns, he favoured the alternative of employing his athletic son at other tasks.”

To think that William had no degree of success as a clothier would not be accurate. In most of the Batley Parish records for the birth of his children, he is listed as a clothier. He probably maintained that profession until he moved to Bruntcliffe in 1808 when his son’s Thomas and Edward began to take over. Some of his success can be judged by the following, written by Philip Henry Booth in his “History of Gildersome”, it demonstrates that William had money to invest in a health insurance plan. “In the year 1798 a Sick Club was formed in the Township, to which Members contributed quarterly, and from the funds of which allowances were made to members in case of sickness, and to widows or representatives in case of death. The Society was flourishing at one time and had accumulated funds to the extent of ₤1,200, but as other Clubs were started, and young men ceased to enter, it was ultimately wound up about the year 1854. On the first page of the book I find the following members enrolled: ................

.............. 1789 Oct. 17th Bilbrough, William aged 26 Clothier..........”

“Now, when he had finished his apprenticeship, he saw and admired a soldier’s daughter of the name of Hargraves. How it all came about I am unable to describe. His apprenticeship must have been completed some four years before this period. William and wife moved into the house of small dimensions and situate near to the bottom of the avenue leading up to Harthill House, on the left hand side. At the time of this writing, 1906, it must have been demolished more than 40 years, he entered that house in 1795.”

As a clothier he probably traveled to Leeds on some market days to sell his wares. It must have been on one of these trips that William met Hannah Hargraves (or Hargreaves), whose father may have operated a booth at one of the “cloth halls”. Best indications are that Hannah was Hannah Robinson Hargreaves b. 29 Sep 1774 in Holbeck, a district of Leeds. And that her parents were Joshua Hargreaves and Mary Askee. They were married in September of 1796 in Leeds, in order to be close to the bride’s family, but the happy couple decided to live at Sharp House adjacent to his parent’s Harthill House. Their first child, Elizabeth, was born there two months later (in those days, couples were often married when the bride was pregnanant). The couple continued to live in Gildersome where they had seven more children, many of which seem to have been named after Hannah’s brothers and sisters.

“John Wheater took Hannah’s sister, Sarah, for his wife, he resided I think at New Wortley but at that period the fields hardly knew a house. My Grandfather’s brother-in-law Wheater always used to speak of Hargraves the manufacturer as his cousin, lately the firm has been known as “Hargraves and Nussey” of Low Wortley. John Wheater often came to our house and he would recount the acts of his brother, Willie, who was for a time with Pablo’s, that famous circus which often visited Leeds, thus connected, he would often get in free. Willie used to be advertised in papers and placard upon the walls as “Willie Wheater the Yorkshire Leaper”

As the years passed at Harthill House, James Bilbrough’s sons took over more of his operations. John, took over the farming and malting probably with help from James. William ran the cloth making processes with Joseph and Samuel, first as apprentices and then as assistants. When their father died in 1805, the Bilbrough brothers continued to stick together and maintained their prior arrangements. James’ Will left all property and money to his wife, Martha, and it appears that she invested money in her son’s various business schemes. Deeds and documents indicate that William, James and John, as partners, were buying and some properties in Gildersome to enlarge the farming business. While Joseph and Samuel had dreams of exporting cloth to the now prosperous American markets and eventually took over the clothing business.

Right, circa 1900, the “Old Stone Cottage” later called Rose Cottage is on the left. The attached buildings left of that is the Angel Inn. The tall building behind is Bruntcliffe Mill sitting on the location of Plantation House and the Maltkiln Yard. Picture courtesy of the Morley Archives

In 1808, William and Hannah’s family had grown to six children with another on the way. Though the youngest four girls were able to double up, the small Sharp’s House could no longer hold such a large family. The decision was made to move to Bruntcliffe and into the Bilbrough’s ancestral home, the “Old Stone Cottage”, built by William’s grandfather around 1740. Their mother, Martha, held the leasehold to the cottage and at the time of her husband’s death it was occupied by a tenant who, I believe, moved out in 1808. That corner of Bruntcliffe I call “Bilbrough’s Corner”. William’s Uncle and Aunt, John and Elizabeth Bilbrough, lived with Benjamin and Martha Mitchell at the Mitchell House (see map), Martha was their daughter. The Mitchells carried on the Cloth Dressing business of the elder John Bilbrough. The Angel Inn, built by William’s Uncle John circa 1780, was run and occupied by Thomas and Ann Helliwell, Ann was another of Uncle John’s daughters. And the fields behind the Mitchell House were owned by Joseph Asquith, one of William’s uncles.

BRUNTCLIFFE CROSSROADS CIRCA 1814 (left)

made for Lord Dartmouth Map courtesy of the Morley Archives 1. Helliwell’s Angel Inn. and “Old Stone Cottage

2. The Mitchell House

3. (red circle) Lister’s Prospect House & Property.

4. Location of the “Old Thatched Cottage”

5. Helliwell’s Brewhouse

6. Plot, recently purchased by John Bilbrough.

7. Shoulder of Mutton Inn, still in business today.

8. Darthmouth’s Quarry9. Parcels for sale, “New Morley Enclosure Act”

A few years later, in 1813, his brother John married Elizabeth Priestley and received a large dowery and annuity, John was ready to invest. John and William, as partners leased the eight acre Lister parcel behind the Angel Inn (see map), described in the deed of lease as, “Dwelling House with the Maltkiln Barn Stable Pigeon Cote and Summer House and other Out Buildings Garden Orchard and Appurtenances”. Immediately after their marriage, John and his bride moved into Prospect House, behind Rose Cottage. John continued to purchase and lease more property in Bruntcliffe until eventually the size of his acreage totaled 35 to 40 acres. William was a partner in the Lister parcel but whether he had a share in any of the others is not known. John, without William, also purchased more land in Gildersome. The years that followed, up to the early 1820’s was an expansion period for the Malting business. Enlisting William’s sons, Thomas and Edward, they built a second malt kiln in Gildersome, attached to Harthill House and a second one at Listers. 1814 saw the birth of Joseph Brooks Bilbrough, son to John and Elizabeth at Plantation House. Elizabeth Priestley Bilbrough did not care for life at Bruntcliffe and longed to be closer to her sister at Gildersome, Ellen Bilbrough who married James. They packed up and moved into Sharp’s house where William and family had lived a few years prior. John, with his newly gotten wealth was now clearly in charge of their farming and malting business and worked out an agreement whereby William would manage operations at Bruntcliffe and John would do the same at Gildersome.

Life at Bruntcliffe between 1808 and 1822 was good. William and Hannah’s last child, Hannah Bilbrough was born in Rose Cottage. William oversaw the expansion of his business, that included the new farmland and extra Kiln. He directed the malt production and kept up his clothier business during the colder months and saw to the crop yield during the planting and harvesting months. He did not lack for a labor force, by 1820, the extended Bilbrough family living at the corner, including Helliwells and Mitchells, totaled over 25 souls. His sons, Thomas and Edward, helped in all aspects of William’s endeavors but seemed particularly interested in cloth manufacturing and had dreams of becoming wool merchants and exporters. They put together a shipment of woolen blankets and Thomas, in 1821, followed it to Philadelphia. There, he lived for a time with his first cousin once removed, John Bilbrough, son of William’s Uncle John. Edward sent a few more shipments to Thomas but the venture fizzled out. Edward remained in Bruntcliffe as a cloth maker but Thomas never saw his parents again. During this same period, daughters Elizabeth and Harriet went to live at Gildersome as housekeepers to their grandmother, Martha, and nannies to the children of Aunt Elizabeth.

Hannah, William’s wife, developed a high fever for some length of time and after the fever broke, she was described as, “...physically and mentally incapacitated...”. It fell to the youngest daughter, Hannah, to look after and nurse her poor mother. Around 1823, she became too ill for home care and required institutionalization at a hospital in Wakefield. The financial burden of Hannah’s debility must have been terrific and caused William to spend down most of what he had saved. He sold out his percentage in the partnerships he had with his brothers, mostly John. He still remained as manager at Bruntcliffe but as a salaried employee. His mother had died in 1827 and her estate was divided between her children into equal shares. William received the leasehold to Rose Cottage but any other property or money seems to have been used up for the care of Hannah. Two years later, Hannah died.

The same period saw the marriages of Edward, Elizabeth, Harriet, Nancy and Sarah. The daughters moved in with their husbands but Edward remained in Bruntcliffe. When Edward married, William left Rose Cottage to the him and his wife and moved into the “Old Thatched Cottage” across the street from the Angel (see map of Bruntcliffe). John had leased this corner of the intersection from Lord Dartmouth and it contained a small cottage that probably was a portion of the Old Thorn Inn. When looking at the photo of the “Old Thatched Cottage” above, one can see that it was composed of two separate units, like a duplex. William, nearing 60 years, added on to the small cottage, probably about 1830, and moved in with his daughter Hannah. They both lived at this cottage until William’s death in 1861. In the book, “Morley, Ancient and Modern”, author William Smith devotes quite a bit of a chapter describing this very cottage and what life was like in it fifty years prior to his writing (about 1880). The Chapter starts with a full page photo of the “Old Thatched Cottage” that can be seen at the top of this page. The sketch above is also from the same chapter and depicts the interior of how the cottage may have appeared, one can easily imagine daughter Hannah ironing at the table. Smith also makes the following observation, when referring to walking down the Bradford/Wakefield Rd. just after the Angel Inn, “Sauntering along the “Street’ in the direction of Stump Cross, we have on our left the residences of the Bilbroughs, the Crowthers and the Mitchells, whose ancestors have nestled here for more generations than we dare guess at”.

A double tragedy visited the Thatched Cottage in and about 1832 and 1833. Daughter Mary was a servant to a physician in Leeds when she became ill and had to leave for home. Hannah, her sister, nursed her at that time. Then, sister Martha, who worked as servant to two “maiden”sisters, was about to depart for London, with them, when she first visited her sick sister at Bruntcliffe. There, she contracted the same illness and became bedridden also. Hannah cared for them both but in August of 1832, Mary died and Martha lingered until May of 1833. Around the same time, Yorkshire was ravaged by a cholera epidemic, daughters Mary and Martha appear to have been its victim.

Hannah led a life of service. When 10 to 12 years of age, she lived at Harthill House as servant to her grandmother, Martha Bilbrough. As a teenager at Rose Cottage in Bruntcliffe, she nursed her sick mother. Then at the Thatched Cottage, she nursed her dying sisters and provided for her father’s needs for almost another thirty years. Her sister Elizabeth (Betty), who was married to George Booth and living in Gildersome, fell ill in 1838. Hannah went to nurse her and help with the families five children. Betty died in December of that year and Hannah remained to continue her help to the family. While there, she fell in love with James Booth, George’s brother. The couple agreed to marry but James fell ill and was not expected to live. Hannah discovered she was bearing James’ child and when she could not hide the fact any longer she told her father. On May 30, 1839, Hannah bore a son, she named him William. James Booth recovered after the birth but it was decided that Hannah should remain unmarried. Her son, William Bilbrough, is the same William “Booth” Bilbrough that wrote the journals and dairies that I have used as a source for these pages. The middle name, Booth, I have given to him to help in identifying him from all the other William Bilbroughs, the most popular name in the Bilbrough family. William Booth lived with his grandfather for 22 years.

Left: William Booth Bilbrough courtesy of his great-great granddaughter, Judith Burton nee Bilbrough. Again, William Booth Bilbrough:

"My grandfather left the little house where he led his loving wife and in 1808, went to reside in Bruntcliffe in a more commodious house. His brother John appears to have been the principle director of the business. At that time, my Grandfather was to receive for his services, 21 shillings per week to be rent free and to have a cow kept. These were, at the time, considered to be good terms. My Grandfather looked after the farm that was rented of Lord Dartmouth consisting of eight fields, five of them were pasture lands, and the three lower down were used for growing oats, wheat, turnips and Potatoes. In those fields I have spent thousands of hours. I am of the opinion that John Bilbrough perhaps rented the malt kilns of the company and afterwards bought them. If that be so, another farm of about the same size would have to be added to the one I have before described, making a farm of about 80 acres in the malt making process. There were two cisterns in which to steep the barley, two low floors and two drying kilns, a large one and a small one, one with four fires and one with 2 fires. I will describe some of the particulars respecting the large Drying Kiln. Cinders were used of good quality, the furnaces were arched over on each side of the respective fires and the further end from the stoker, there were apertures, 4 on each side and 2 at the end of each of the fires, in order that the heat might radiate in uniformity underneath the perforated plates or tiles upon which the Baptizes Barley, after being three days in the crock, and made a pilgrimage of about 12 stages along the lower ?????? floor, it was pitched by a large wooden shovel into the “torrid zone” and after having taken into its constitution a certain defined quantity of heat, it assumes another name, that of Malt. These remarks are for the uninitiated. My Grandfather once took me to see this larger Drying Place when I was about 5 years old but there were but two fires that I could see, but to our right there was a dark passage, my guardian invited me to follow him which I did. This was to me unexplored geography, having traveled the passage, I found to my surprise, it led to another stoke room, but more comfortable and more retired with arched roof from which there was suspended a lamp to defuse the light. Its fires looked red and inviting and immediately in front and on one side were two seats fixed, here it did seem to me to be a rallying place to spend a few quite hours when the labours of the day were finished and the stoker would be glad of their company and conversation. Perhaps here, Mr. John, the Master and my grandfather, would discuss every conceivable subject relating to the customers, the malt process, the farm, and the cattle.

Customers would try to keep on courteous terms with my Grandsire for he kept the key of the beer cellar in the large house in which I believe John Bilbrough resided for a short time, but his wife I think did not care for Bruntcliffe but wished to be down in Gildersome near to her sister. Now the Beer Cellar approached from the outside, and no doubt they would occasionally get round my Grandfather, who was good natured, and get some of the special Beer. This beer was brewed mainly for customers who came for Malt, as kind of a recommendation, it was made very good, it was not such as they sell in public houses now. My mother used to brew 3 strokes and 1 peck, that was the malt used, and she did not make a large quantity, so you will see it was a treat to those who liked beer."

Left: Bruntcliffe from an 1854 Army Survey

"Let me tell the story of the good dog Peroe. This dog had an excellent reputation, good, kind, quiet but with respect to rats, he knew what was expected of him and he courageously did his duty. I have heard my Grandfather speak of his achievements and I will recount one of his performances; in one of the cisterns when empty of water there were 4 big rats looking out, I suppose, for any barley that might be left. Peroe’s attention was drawn to the scene of operation with alacrity, he did jump in amongst them, pick them up and shake them and break the backbone of each of them, and then he got upon the edge of the cistern, looked at my Grandfather, and if he had known the English language and could have spoken, perhaps he would have said, “That’s the way to polish them off”, and if he got a few pats upon the back and a tender stroke of the head, he considered himself amply rewarded. We must admit that to attack the rats, he put himself into some danger, for rats when they are pinned will combine and make common cause against the enemy. What is wanted in a dog for this work is courage, precision and dispatch. Those who read these writings of mine will observe that I have made a digression, but still some very valuable information has been rendered."

When William’s grandson wrote above, about visiting the malt kilns when he was 5 years old, William was 73. His brother John was 62 at the same time, and was retiring from his malt and farming operations. John groomed his son Alfred to take over, who was in his early 20’s and more active. During the 1840’s John sold about half of his holdings in Bruntcliffe but retained the leaseholds to the malt yard and the farm across Bruntcliffe Lane including the Old Thatched Cottage where William resided. William Radford Bilbrough, writing about 1900, stated that when John, died in 1850, Alfred continued the lease of the farm and thatched cottage, at a loss, just to provide William with a place to live. Alfred gave up the lease to the malt yard and soon Prospect Mills was erected on the spot, operated by Thomas Stephenson. Prospect Mill later became known as Bruntcliffe Mill and can be seen in the photo above behind the Old Angel Inn. Again from “Morley, Ancient and Modern”, “Prospect Mill, Bruntcliffe, stands on the site of the extensive malt-kilns, formerly in the occupation of the Bilboroughs, a name like Crowther, indigenous to Bruntcliffe. The kilns were converted into a woolen mill about thirty years ago.”

William was also looked after in the Wills of many of his brothers and sisters and so was able to maintain a comfortable life until the end. In the 1841 census, William, aged 70, was living with Hannah, her son William (2 yrs old) and grandson Thomas, Edward’s son; William’s occupation is noted as “Maltster”. The 1851 census finds 80 year old William, a “Retired Maltster”, occupying the same home with daughter Hannah and her son William. 1861. At age 90, the census that year, lists William as “Farmer”, Hannah and William are again co-occupants. A few months after the 1861 census recorded his presence, William died, he was 90 years old. he had lived at least 30 years at the “Old Thatched Cottage”, sharing it at times with his unwed daughters and various grandchildren. His daughter Hannah remained to care for him as he aged.

Above is the registered death entry for William. The “James Bilbrough in attendance” was William’s grandson James born 1838, he was Edward’s son.

William Radford Bilbrough, wrote this in his diary:

“Feb. 13 1858 This afternoon Pa & I went to Morley by train and walked to Bruntcliff and saw Old Uncle William and looked round the garden.” “Aug 22, 1861 Thr. Old Uncle William died aged 90.”

After William’s death, Alfred gave up the leasehold to the farm and cottage to the Helliwells. Hannah and her son William were invited to move into the old part of Harthill House in Gildersome and remained there for some time. Edward, having some success in the cloth business, purchased Rose Cottage from Lord Dartmouth. His descendants continued to live there until about 1905, it was torn down in the 1960’s after about 200 years of occupation by the Bilbroughs.