Gildersome’s First National School by Andrew Bedford © 2019

James Thomas Brudenell in a more familiar pose.

James Thomas Brudenell in a more familiar pose.

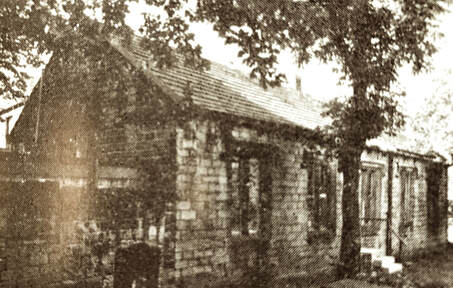

The building above, now part of St Peter’s Church, has served a variety of purposes since its erection in the 1830s. During the course of my lifetime, it has been used as a youth club, a venue for night school classes and as an annex for a Morley secondary school. Around 1900 it was Gildersome’s Conservative Club and during World War Two it was apparently used by Air Raid Wardens. Originally, however, it was Gildersome’s first National School.

On the 24th of March 1840, an indenture of lease and release was signed by the Right Honourable James Thomas Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan (of Light Brigade fame). Other signatories included Andrew Guyse Kinsman, perpetual curate of Gildersome, along with churchwardens Thomas Stephenson and Isaac Mitchell. This indenture granted a parcel of land upon which the buildings erected thereon may forever hereafter be used for the purpose of a school to be united into the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in England and Wales. (1) Thus, Gildersome’s first National School was formally inaugurated.

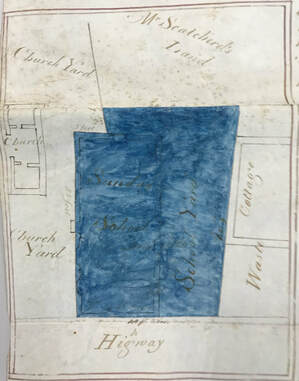

However, there is a strong possibility that the school was already in use in some capacity by 1837 (probably as the church Sunday school) and may have been in commission as early as 1834. The outline plan affixed to the indenture shows a school building already in situ at the time the indenture was signed. This appears to confirm that the school building was already in place before 1840. If this is the case, then reasons for the apparent delay in drawing up the indenture need to be considered. It seems to me very plausible that the death of Robert Brudenell, 6th Earl of Cardigan, in 1837, might have necessitated the postponement. It is not beyond possibility that some form of agreement had been reached prior to the 6th Earl’s death and that the legal formalities had been delayed by the constitutional complexities associated with succession and inheritance. Consequently, when the 7th Earl signed the indenture, the school had already been established.

On the 24th of March 1840, an indenture of lease and release was signed by the Right Honourable James Thomas Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan (of Light Brigade fame). Other signatories included Andrew Guyse Kinsman, perpetual curate of Gildersome, along with churchwardens Thomas Stephenson and Isaac Mitchell. This indenture granted a parcel of land upon which the buildings erected thereon may forever hereafter be used for the purpose of a school to be united into the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in England and Wales. (1) Thus, Gildersome’s first National School was formally inaugurated.

However, there is a strong possibility that the school was already in use in some capacity by 1837 (probably as the church Sunday school) and may have been in commission as early as 1834. The outline plan affixed to the indenture shows a school building already in situ at the time the indenture was signed. This appears to confirm that the school building was already in place before 1840. If this is the case, then reasons for the apparent delay in drawing up the indenture need to be considered. It seems to me very plausible that the death of Robert Brudenell, 6th Earl of Cardigan, in 1837, might have necessitated the postponement. It is not beyond possibility that some form of agreement had been reached prior to the 6th Earl’s death and that the legal formalities had been delayed by the constitutional complexities associated with succession and inheritance. Consequently, when the 7th Earl signed the indenture, the school had already been established.

What can be said with certainty, however, is that on the 24th of May 1840, the school at Gildersome was awarded a grant from the Lords of the Treasury amounting to £73, effectively confirming its status as a National School. The timing of the award (just two months after the indenture was signed) suggests that the school had been waiting for the appropriate legal documentation in order to support its application for the award. This also supports the suggestion that the school might have been operating, in some form or other, before 1840.

Left, the plan from the 1840 Cardigan grant. (click to expand) The outline of the school can be seen in the left of the blue shaded area, indicating that the building was in place at the time the of the agreement.

What can be said with certainty, however, is that on the 24th of May 1840, the school at Gildersome was awarded a grant from the Lords of the Treasury amounting to £73, effectively confirming its status as a National School. The timing of the award (just two months after the indenture was signed) suggests that the school had been waiting for the appropriate legal documentation in order to support its application for the award. This also supports the suggestion that the school might have been operating, in some form or other, before 1840.

Left, the plan from the 1840 Cardigan grant. (click to expand) The outline of the school can be seen in the left of the blue shaded area, indicating that the building was in place at the time the of the agreement.

Documents confirm that the grant awarded could have been used for any of the following purposes: building, enlargement, improvement or fixtures. (2) Given that a similarly sized school building had been erected on the Town Green some thirty years previously at a cost of around £200, it seems very unlikely that the grant would have covered building costs. It appears to me that the most likely explanation is that the grant was used to provide lavatories. There is no evidence of a lavatory building in the schoolyard on the 1840 indenture plan, though the photograph below shows a small, flat roofed building at the rear of the school. We can also say with certainty that by 1846, as will be seen below, the school’s lavatories were in place and attracting the disapproval of school inspectors.

In 1844, the school made a further application for a grant to provide desks and seating. It appears, however, that this application proved unsuccessful, as no award appears to have been recorded in that year. However, the school did receive a grant of £10 in 1846 and a further £6 10s in 1847. From a contextual perspective, the significance of this financial support cannot be underestimated, given the economic circumstances of the period. The 1840s are often referred to as the “hungry forties” so not only is it likely that government funding would be difficult to secure, the financial burden of establishing a school for children unable to pay for their education must have been considerable.

Right, The National School photographed from within the Churchyard. Note the flat roofed building partially hidden by a wall at the rear: probably lavatories added after the original building work had been completed.

Aside from monies provided by government, National Schools were established by the Church of England and were expected to be partially supported at a local level by the parish. It is evident from the 1840 indenture that this had been the case at Gildersome. The document confirms that the cost of building the school had been met by funds held by the curate, Andrew Guyse Kinsman, and churchwardens of Gildersome; the accumulation of which must have been a considerable effort given the economic context. In 1847, we are told that the annual cost of running the school amounted to £31. This was met by a yearly endowment of £6, along with school pence (nominal charges made to parents) amounting to £15 and £10 from other sources (probably some form of public subscription). (3)

The endowment alluded to above was the Bolton Hargrave charity that had previously supported the Old Town School (4) by providing funding to enable ten poor boys to read the Bible and repeat the Church Catechism. The Old Town School stood on what is now Church Street, nearly opposite the New Inn. It occupied a space close to three cottages, the rents from which constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity and provided a yearly endowment for the education of ten poor children at the school. That the National School came to be supported by the same endowment suggests that the Old Town School had been abandoned before 1840. It is evident that the two establishments shared the same underpinning values. Schools operating under the National system were also expected to focus on the scriptures, liturgy and catechism of the Church of England and required the superintendence of a clergyman. It was also stipulated that any masters and mistresses employed at a National School had to be members of the Church of England.

Another condition of membership was the imposition of a yearly inspection. Mr Watkins’ inspection report of 1844 (5) states that the schoolroom at Gildersome was being utilised on Sundays only, remaining unused during the week due to lack of sufficient funds, another indicator, perhaps, of the economic climate. The report goes on to explain that Gildersome’s clergyman (6) was unable to raise a salary for a master. By 1846, however, the inspector was able to report that the school was operating full time. Unfortunately, the quality of provision appears to have been less than satisfactory and the inspector’s report more than a little critical. The report states somewhat pointedly that ‘there are four classes (so called) of boys and girls together, under an untrained and ignorant master, who seems to know little about his duties’ and that ‘the outbuildings (i.e. lavatories) are in a most filthy state.’ In the following year the school appears to have made little by way of improvement with the inspector again confirming that ‘this is a mixed school of boys and girls, in a very poor state of discipline, and making little progress.’ (7) The inspector concludes by stating that ‘the master is 73 years old [and] was formerly a clothier, [who] took to schooling.’ By 1868, there are signs of moderate improvement. Mr Pickard’s General Report states that ‘the children of this school read passably, but very few, even in the first class, can write from dictation, and only six in the whole school can work simple sums in arithmetic. The lowest class knew nothing of the creation or the birth of Christ [and] the upper classes knew very little of either Old or New Testament history.’ (8) It is perhaps encouraging to note that while academic improvement appears to have been marginal, the situation with the lavatories seems to have been rectified to the inspector’s satisfaction.

In 1844, the school made a further application for a grant to provide desks and seating. It appears, however, that this application proved unsuccessful, as no award appears to have been recorded in that year. However, the school did receive a grant of £10 in 1846 and a further £6 10s in 1847. From a contextual perspective, the significance of this financial support cannot be underestimated, given the economic circumstances of the period. The 1840s are often referred to as the “hungry forties” so not only is it likely that government funding would be difficult to secure, the financial burden of establishing a school for children unable to pay for their education must have been considerable.

Right, The National School photographed from within the Churchyard. Note the flat roofed building partially hidden by a wall at the rear: probably lavatories added after the original building work had been completed.

Aside from monies provided by government, National Schools were established by the Church of England and were expected to be partially supported at a local level by the parish. It is evident from the 1840 indenture that this had been the case at Gildersome. The document confirms that the cost of building the school had been met by funds held by the curate, Andrew Guyse Kinsman, and churchwardens of Gildersome; the accumulation of which must have been a considerable effort given the economic context. In 1847, we are told that the annual cost of running the school amounted to £31. This was met by a yearly endowment of £6, along with school pence (nominal charges made to parents) amounting to £15 and £10 from other sources (probably some form of public subscription). (3)

The endowment alluded to above was the Bolton Hargrave charity that had previously supported the Old Town School (4) by providing funding to enable ten poor boys to read the Bible and repeat the Church Catechism. The Old Town School stood on what is now Church Street, nearly opposite the New Inn. It occupied a space close to three cottages, the rents from which constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity and provided a yearly endowment for the education of ten poor children at the school. That the National School came to be supported by the same endowment suggests that the Old Town School had been abandoned before 1840. It is evident that the two establishments shared the same underpinning values. Schools operating under the National system were also expected to focus on the scriptures, liturgy and catechism of the Church of England and required the superintendence of a clergyman. It was also stipulated that any masters and mistresses employed at a National School had to be members of the Church of England.

Another condition of membership was the imposition of a yearly inspection. Mr Watkins’ inspection report of 1844 (5) states that the schoolroom at Gildersome was being utilised on Sundays only, remaining unused during the week due to lack of sufficient funds, another indicator, perhaps, of the economic climate. The report goes on to explain that Gildersome’s clergyman (6) was unable to raise a salary for a master. By 1846, however, the inspector was able to report that the school was operating full time. Unfortunately, the quality of provision appears to have been less than satisfactory and the inspector’s report more than a little critical. The report states somewhat pointedly that ‘there are four classes (so called) of boys and girls together, under an untrained and ignorant master, who seems to know little about his duties’ and that ‘the outbuildings (i.e. lavatories) are in a most filthy state.’ In the following year the school appears to have made little by way of improvement with the inspector again confirming that ‘this is a mixed school of boys and girls, in a very poor state of discipline, and making little progress.’ (7) The inspector concludes by stating that ‘the master is 73 years old [and] was formerly a clothier, [who] took to schooling.’ By 1868, there are signs of moderate improvement. Mr Pickard’s General Report states that ‘the children of this school read passably, but very few, even in the first class, can write from dictation, and only six in the whole school can work simple sums in arithmetic. The lowest class knew nothing of the creation or the birth of Christ [and] the upper classes knew very little of either Old or New Testament history.’ (8) It is perhaps encouraging to note that while academic improvement appears to have been marginal, the situation with the lavatories seems to have been rectified to the inspector’s satisfaction.

When the 1st St Peter's was destroyed by fire in 1874, the Church School was untouched.

When the 1st St Peter's was destroyed by fire in 1874, the Church School was untouched.

The inspector’s report for 1847 shows that the number of children attending the school regularly amounted to thirty, with forty children present at examinations. (9) These figures are perhaps indicative of an underlying resistance to education and the economic pressures on families dependant on the supplementary earnings of their children. In 1847, the children who attended the school were taught by a single teacher. Unfortunately, there is little documented evidence of the teachers employed at Gildersome’s first National School and the evidence that does remain is somewhat sketchy. A directory dated 1841 confirms that Samuel Firth was conducting a school in Gildersome at the time of publication. (10) Firth had previously been at the centre of an unseemly dispute between the churchwardens and nonconformists at another school in the township. Firth had conducted a daily school at the New Sunday School on the Town Green during the 1830s. Having sided with the churchmen in that confrontation, it is not beyond possibility that Firth might have taken the position of master at the new church school at its inception. However, if this is so, the appointment must have been short lived. As we have seen above, by 1844 there was no master in place. In a directory published in 1847, James Webster is listed as running one of three academies in Gildersome: Hannah Marsden and Caleb Peat running the others. (11) As Webster’s school is distinguished from the other two as being “free of charge”, there is a strong possibility that this was the National School. According to census information, Webster would have been aged around 70 in 1847, which also aligns to some degree with the inspector’s comments above.

It is also evident that the post of teacher at the school was perhaps a little transient. Joseph Crossland occupied the post between 1869 and 1870, followed by Samuel Turner 1870 to 1872. A period of stability was presided over by Annie Otter who occupied the position between 1872 and 1894. Miss Otter was followed by Mary Elizabeth Douthwaite 1894 to 1896 and Henry Holgreaves 1889 to 1898. (12)

It is also evident that the post of teacher at the school was perhaps a little transient. Joseph Crossland occupied the post between 1869 and 1870, followed by Samuel Turner 1870 to 1872. A period of stability was presided over by Annie Otter who occupied the position between 1872 and 1894. Miss Otter was followed by Mary Elizabeth Douthwaite 1894 to 1896 and Henry Holgreaves 1889 to 1898. (12)

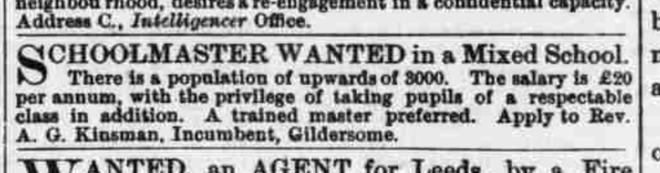

The advert above from 1866 provides an insight into the terms and conditions offered to schoolmasters by the National School and the financial constraints under which the school was operating. A salary of £20 per year is offered, with an additional opportunity to supplement this income with private tuition. The perceived necessity to augment the master’s wages in this way suggests that the salary offered would be unlikely to attract qualified candidates. The fact that a “trained master [was] preferred” underlines the point by suggesting that unqualified applicants would at least be considered. That Kinsman chose to describe fee-paying scholars as “pupils of a respectable class” is perhaps indicative of deep-seated social prejudice that would have placed further constraints on the education of Gildersome’s poor.

Despite financial restrictions and a series of uncertain beginnings, the first National School continued to operate on the same site until it was replaced, in 1897, by a more commodious building a little further along Church Street. This was the site previously occupied by three cottages, the rents from which had constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity. That a project to educate children from poor families was conceived and delivered during what is generally regarded as the worst economic depression of the nineteenth century is perhaps testimony to the tenacity of Andrew Guyse Kinsman, Gildersome’s perpetual curate, and his churchwardens. It might also be suggested that the fact that the same building is still playing a part in the local community is reflective of the value of Kinsman’s legacy.

Despite financial restrictions and a series of uncertain beginnings, the first National School continued to operate on the same site until it was replaced, in 1897, by a more commodious building a little further along Church Street. This was the site previously occupied by three cottages, the rents from which had constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity. That a project to educate children from poor families was conceived and delivered during what is generally regarded as the worst economic depression of the nineteenth century is perhaps testimony to the tenacity of Andrew Guyse Kinsman, Gildersome’s perpetual curate, and his churchwardens. It might also be suggested that the fact that the same building is still playing a part in the local community is reflective of the value of Kinsman’s legacy.

1) WYAS, WDP26/7/3

2) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

3) Ibid.

4) The Old Town School stood on Town Street, nearly opposite the New Inn. It occupied a space close to three cottages, the rents from which constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity and provided a yearly endowment for the education of ten poor children at the school. That the National School was supported by the same endowment suggests that the Old Town School had been abandoned before 1840. The three cottages were demolished around 1890 and the site used for the erection of the second National School in 1896.

5) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

6) Andrew Guyse Kinsman was perpetual curate of Gildersome from 1819 to 1867.

7) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

8) Ibid.

9) Ibid.

10) White’s Directory, 1841.

11) White’s Directory, 1847.

12) Dennis Barraclough: Short History of the Church and Parish of Gildersome (1974)

2) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

3) Ibid.

4) The Old Town School stood on Town Street, nearly opposite the New Inn. It occupied a space close to three cottages, the rents from which constituted the Bolton Hargrave Charity and provided a yearly endowment for the education of ten poor children at the school. That the National School was supported by the same endowment suggests that the Old Town School had been abandoned before 1840. The three cottages were demolished around 1890 and the site used for the erection of the second National School in 1896.

5) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

6) Andrew Guyse Kinsman was perpetual curate of Gildersome from 1819 to 1867.

7) Minutes of The Committee of Council on Education with Appendices. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

8) Ibid.

9) Ibid.

10) White’s Directory, 1841.

11) White’s Directory, 1847.

12) Dennis Barraclough: Short History of the Church and Parish of Gildersome (1974)