The New School on the Green by Andrew Bedford © 2018

|

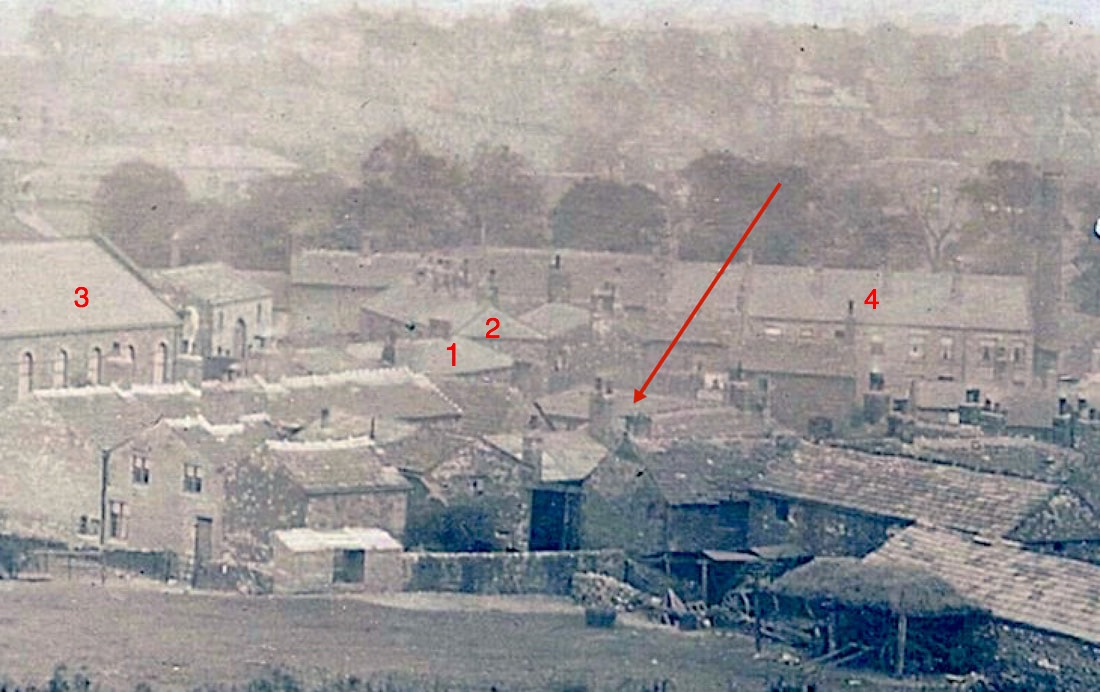

The 'New School,' the single storey building arrowed (above) stood at the junction of Mill Lane and Town End Street. It is opposite to the end of Clayton Fold (1), which, until the 1940s, reached down to the roadside at Town End Street. The gable end just beyond the end of Clayton Fold is that of the Miners’ Arms (2). Also shown is Greenside Methodist Chapel (3) and Grove View (4).

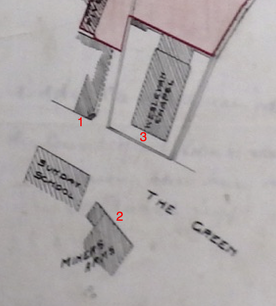

The single storey building is the Sunday School in the plan left. |

From a modern perspective, the establishment, in 1810, of a school for the labouring classes might appear to be a relatively straightforward process of social improvement. However, contemporary parliamentary debates suggest otherwise, as this extract from a speech made by Tory MP Davies Giddy in 1807 underlines:

However specious in theory the project might be of giving education to the labouring classes of the

poor, it would, in effect, be found to be prejudicial to their morals and happiness; it would teach them

to despise their lot in life, instead of making them good servants in agriculture and other laborious

employments to which their rank in society had destined them. (1)

It is evident, therefore, that there was opposition to the idea of educating the lower orders, especially from those, like Mr Giddy, who felt that the country’s economic structures were dependent upon their continuing ignorance. This was not a perspective that was shared universally, however. A more liberal perception of education is exemplified by words attributed to Robert Raikes, the person credited with the creation of the Sunday school movement

Ignorance is the root of degradation …

Idleness is a consequence of ignorance,

Idleness begets vice, and vice leads to the gallows. (2)

According to Raikes, ignorance leads ultimately to crime, therefore educating the young will reduce criminality. It is evident that these sentiments had been shared by the Gildersome diarist (William Radford Bilbrough) who was moved to make the following complaint in the mid nineteenth century:

Notwithstanding the united efforts put forth in connection with the School on the Green, there were

sadly too many ignorant youths with nothing better to do than get into mischief. (3)

We might infer from this that what the diarist refers to as the “School on the Green” had been conceived as a means of not only educating Gildersome’s children, but also of improving their behaviour for the common good. A school essentially inspired by liberal ideals. What follows is the culmination of my research into the conception, realisation and ultimate demise of what came to be known as the New School on the Green

However specious in theory the project might be of giving education to the labouring classes of the

poor, it would, in effect, be found to be prejudicial to their morals and happiness; it would teach them

to despise their lot in life, instead of making them good servants in agriculture and other laborious

employments to which their rank in society had destined them. (1)

It is evident, therefore, that there was opposition to the idea of educating the lower orders, especially from those, like Mr Giddy, who felt that the country’s economic structures were dependent upon their continuing ignorance. This was not a perspective that was shared universally, however. A more liberal perception of education is exemplified by words attributed to Robert Raikes, the person credited with the creation of the Sunday school movement

Ignorance is the root of degradation …

Idleness is a consequence of ignorance,

Idleness begets vice, and vice leads to the gallows. (2)

According to Raikes, ignorance leads ultimately to crime, therefore educating the young will reduce criminality. It is evident that these sentiments had been shared by the Gildersome diarist (William Radford Bilbrough) who was moved to make the following complaint in the mid nineteenth century:

Notwithstanding the united efforts put forth in connection with the School on the Green, there were

sadly too many ignorant youths with nothing better to do than get into mischief. (3)

We might infer from this that what the diarist refers to as the “School on the Green” had been conceived as a means of not only educating Gildersome’s children, but also of improving their behaviour for the common good. A school essentially inspired by liberal ideals. What follows is the culmination of my research into the conception, realisation and ultimate demise of what came to be known as the New School on the Green

There is a passage in Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley in which the protagonist is leading a procession of church-school children. As they turn a corner, they are confronted by another contingent of children marching in the opposite direction. The narrator describes how this rival group, comprising of ‘the Dissenting and Methodist schools, the Baptists, Independents, and Wesleyans, joined in unholy alliance’ intended to obstruct the progress of the church scholars and drive them back. (4) Unsurprisingly, given Ms Bronte’s Anglican upbringing, the church party, armed with little more than a sense of righteousness and a rousing rendition of Rule Britannia, succeeded in putting the “unholy alliance” of nonconformist scholars to flight. While the passage may appear inconsequential and perhaps slightly bemusing to modern readers, the circumstances and sentiments described in the passage would have been very familiar at the time of publication (1848). This fictional clash of sectarian scholars illustrates a point made by GM Trevelyan: that, in the mid-nineteenth century, education had become a battleground for the established church and the nonconformists. (5) It is also worth noting that political conflict in the nineteenth century had less to do with class divisions than with religious ones; the Tory party being closely associated with the Anglican Church and the Liberals and Radicals tending to affiliate with the nonconformists. The following will examine the emergence of educational provision for Gildersome’s children within the wider context of nineteenth-century political and interdenominational hostility.

The Parliamentary Gazetteer, issued in 1847, states that Gildersome had two daily schools, one of which had an endowment of six pounds per year. This probably refers to a bequest made by Bolton Hargrave in 1749, which provided funding for the education of ten children from poor families.

A deed registered in 1850, Cardigan to the Churchwardens and Overseers of Gildersome, states that ‘many years ago’ a school and two cottages had been ‘erected at the expense of the inhabitants of Gildersome [and] are now in the possession of the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of Gildersome tenants thereof of the said Earl at a nominal rent.’ (6) The two cottages are identified in the deed as being situated on the Earl’s land at Harthill Bottom and were used by the overseers as accommodation for paupers. The whereabouts of the school is not made explicit though the deed records that it was bounded on all sides by waste lands of the Manor of Gildersome. The small building on the 1800 map is consistent with this description, being situated on the town’s waste. We may reasonably assume, then, that the earliest of the schools mentioned in the Gazetteer, the “Old Town School,” was situated on what would become known as Church Street, on the opposite side to and somewhat below the Baptist Chapel.

1800 map showing the Old Town School building located on what is now Church Street. The chapel building (bottom right) is the first St Peters, originally built as a chapel of ease.

The Parliamentary Gazetteer, issued in 1847, states that Gildersome had two daily schools, one of which had an endowment of six pounds per year. This probably refers to a bequest made by Bolton Hargrave in 1749, which provided funding for the education of ten children from poor families.

A deed registered in 1850, Cardigan to the Churchwardens and Overseers of Gildersome, states that ‘many years ago’ a school and two cottages had been ‘erected at the expense of the inhabitants of Gildersome [and] are now in the possession of the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of Gildersome tenants thereof of the said Earl at a nominal rent.’ (6) The two cottages are identified in the deed as being situated on the Earl’s land at Harthill Bottom and were used by the overseers as accommodation for paupers. The whereabouts of the school is not made explicit though the deed records that it was bounded on all sides by waste lands of the Manor of Gildersome. The small building on the 1800 map is consistent with this description, being situated on the town’s waste. We may reasonably assume, then, that the earliest of the schools mentioned in the Gazetteer, the “Old Town School,” was situated on what would become known as Church Street, on the opposite side to and somewhat below the Baptist Chapel.

1800 map showing the Old Town School building located on what is now Church Street. The chapel building (bottom right) is the first St Peters, originally built as a chapel of ease.

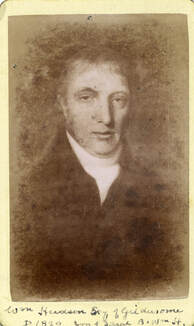

The second school alluded to by the Gazetteer is likely to be the one conceived in 1809 when William Hudson, along with Messrs John and James Bilbrough, proposed building a school by subscription. (7) In the following year, what came to be known as the New School (8) was erected on common land in the possession of the Earl of Cardigan, and the beneficence of the subscribers was immortalised on a board that hung in one of the schoolrooms. (9) The date (1810) was also carved on a lintel above the door. The school consisted of two rooms: a large room for the boys and a smaller room for the girls.

The newspaper advertisement (Leeds Times, 1772) confirms the presence of a school at Gildersome in the eighteenth century. It also makes reference to the interest of two hundred pounds being provided for the education of ten boys. It is, therefore, very likely that the unnamed school was in fact the Old Town School.

The newspaper advertisement (Leeds Times, 1772) confirms the presence of a school at Gildersome in the eighteenth century. It also makes reference to the interest of two hundred pounds being provided for the education of ten boys. It is, therefore, very likely that the unnamed school was in fact the Old Town School.

William Hudson James Bilbrough John Bilbrough

of Park House of Park House of Harthill House

(Photos taken in the 1860's of portraits that hung at Park House and Harthill House courtesy of the John Town Collection)

of Park House of Park House of Harthill House

(Photos taken in the 1860's of portraits that hung at Park House and Harthill House courtesy of the John Town Collection)

Despite subscriptions having been drawn from a variety of sources from across the community, it seems that the siting of the school had given cause for concern. Some freeholders in the township had objected to a school being erected in proximity to their properties. After considerable deliberation, however, a site was fixed that was calculated to give offence to no one, being opposite to a freehold property owned by Mr William Hudson, and Messrs John and James Bilbrough, (10) all of whom, as we have seen above, were active proponents of the New School. However, for reasons that remain unclear, the source of this information neglects to mention that the freehold property in question was in fact the Township Workhouse. Whatever the reasons for the informant’s coyness, we might safely assume that the workhouse’s inhabitants would have been unlikely to raise many objections.

The site of the New School is made explicit in a deed registered in 1886 which describes

a certain erection or building then and for some time past divided into and occupied as two school

rooms standing and upon a plot or parcel of land lying and being near the Work House in the

Township of Gildersome and Parish of Batley … bounded eastwardly by the King’s highway leading

from Gildersome aforesaid to the Bottoms, westwardly by certain waste or vacant lands,

northwardly by another highway [Mill Lane] and southwardly by other waste or vacant land. (11)

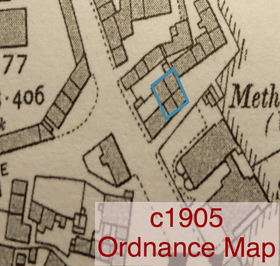

Added to which, a voting list dating from 1840 confirms that James Bilbrough of Gildersome is the owner of a freehold property situated near the New School. The list also confirms that the tenants of that property are Gildersome’s overseers: documentary confirmation that the Township’s workhouse was, at that time, in the possession of James Bilbrough and that the school was situated nearby. A sale map from 1851 places the school at what is now the corner of Mill Lane and Town End Street, but what was then part of the manorial waste or common land more familiarly referred to as “the Green.” The school building is situated directly opposite an area designated “the parish,” a familiar term of reference for the workhouse. Another map of the same period shows the same building (circled) directly opposite to the workhouse (rectangle). A diary entry made in 1885 by a Bilbrough family member states that ‘the old workhouse is now made into cottages which stand opposite to the Town School.’ (12) The 1905 map shows the workhouse building having been divided into cottages and forming part of Clayton Fold; a porch and enclosed yard has been added to the rear of the school building. There can be little doubt, therefore, that the new “School on the Green,” built by public subscription in 1810, was located at the junction of Mill Lane and Town End.

a certain erection or building then and for some time past divided into and occupied as two school

rooms standing and upon a plot or parcel of land lying and being near the Work House in the

Township of Gildersome and Parish of Batley … bounded eastwardly by the King’s highway leading

from Gildersome aforesaid to the Bottoms, westwardly by certain waste or vacant lands,

northwardly by another highway [Mill Lane] and southwardly by other waste or vacant land. (11)

Added to which, a voting list dating from 1840 confirms that James Bilbrough of Gildersome is the owner of a freehold property situated near the New School. The list also confirms that the tenants of that property are Gildersome’s overseers: documentary confirmation that the Township’s workhouse was, at that time, in the possession of James Bilbrough and that the school was situated nearby. A sale map from 1851 places the school at what is now the corner of Mill Lane and Town End Street, but what was then part of the manorial waste or common land more familiarly referred to as “the Green.” The school building is situated directly opposite an area designated “the parish,” a familiar term of reference for the workhouse. Another map of the same period shows the same building (circled) directly opposite to the workhouse (rectangle). A diary entry made in 1885 by a Bilbrough family member states that ‘the old workhouse is now made into cottages which stand opposite to the Town School.’ (12) The 1905 map shows the workhouse building having been divided into cottages and forming part of Clayton Fold; a porch and enclosed yard has been added to the rear of the school building. There can be little doubt, therefore, that the new “School on the Green,” built by public subscription in 1810, was located at the junction of Mill Lane and Town End.

The two schools were similar in size and both comprised of two classrooms, one for girls and the other for boys. A key difference between them was that the older establishment had been conceived as a fee-paying day school funded by charitable subscription. (13) The New School, on the other hand, was conceived as a Sunday school in which all children could access free education on the Sabbath (tuition being provided on a voluntary basis). In 1810, it was still customary to put children to work in some capacity as soon as they were physically capable. The situation changed somewhat when the Factory Act of 1833 legislated against the employment of children under nine years of age and restricted the working hours of children between nine and thirteen years to nine a day. This legislation only applied to factories, however. The collieries continued to employ children as young as five until 1842. (14) Within this context, it appears that a Sunday school offered the most realistic opportunity for children from poorer families to access some form of basic education.

Both schools were also utilised for township meetings. PH Booth tells us that ‘previous to 1809 the two rooms in Gildersome Town Hall [the Old Town School] which stood on the waste beyond the church were used for meetings of the officials of the Township: the overseers, the surveyors and the constable.’ (15) Booth also confirms that the school built at Town End in 1810 was utilised as a committee room by the township when he states that a public meeting had been held at the New School in 1818 to nominate a ‘committee to assist and advise the Overseers of the Poor.’ (16) A meeting in the following month at the same venue established the rules and regulations under which the committee would proceed with their duties. Booth goes on to state that in 1863 a Township meeting was held at the Old Town School concerning the proposed building of the Mount Zion chapel. Booth is clearly differentiating between the New School and the Old School, so we might safely infer that town meetings were held at both venues. He later states that in 1822 the committee resolved to purchase six arm chairs and a deal table for the use of the Town and the Committee’ and that these items were ‘evidently for the [Old] Town’s School which stood on the Green opposite Moorfield House.’ (17) It is unfortunate, however, that Booth neglects to disclose exactly what ‘evidence’ had enabled him to reach his conclusion. Clearly both schools had been used as committee rooms and it may be that in 1822 township meetings were taking place in the Old Town School. However, given the proximity of the date of the recorded meeting in 1818 and that of the purchase, along with the fact that he neglects to provide any supporting evidence, it may be that Booth is making something of an assumption. One might equally assume that a venue in use for over fifty years would already have a table and chairs for the committee, while a relatively new building might not? While it is indisputable that the table and chairs had been acquired for the use of the committee, the dates suggest that they might equally have been purchased to facilitate the committee meetings at the New School.

Alongside township business, the New School building was also utilised during the week as a meeting room by various benefit societies; the Mechanics Institute, for example, used one of the classrooms as a “newsroom”. Additionally, in 1843, a number of lectures were delivered at the New School, including a demonstration of “mesmero-phrenology” which appears to have particularly impressed the audience when a volunteer subject almost fell off the stage during the performance. Another lecture, taking as its subject the “millennium,” failed to excite quite the same level of enthusiasm; the Leeds Times complained that ‘the lecture and discussion [had] only made the darkness on this subject more visible”. (18) In the 1830s, the New School building was also utilised as a fee-paying day school under the tutelage of a person by the name of Samuel Firth, of which more will be revealed below.

The New School’s inception had begun as an amicable enterprise supported by a cross section of the township’s religious institutions and the subscriptions made in 1809 had been drawn from representatives of Gildersome’s various places of worship. Inevitably, some denominations subscribed more than others. The weightiest contribution came from those of the Baptist persuasion whose efforts raised in excess of £100. The Society of Friends donated over £60 and the Methodists a rather modest £16. Bringing up the rear were those from St Peter’s Church whose contribution amounted to a less than impressive £8.10. (19)

Perhaps inevitably, these figures would become an element of contention when what appears to have begun as an amicable cross-denominational enterprise appears to have collapsed into bitter dispute and acrimony.

We are told that the Sunday school was originally staffed by volunteer teachers of several denominations who, at the conclusion of lessons, conducted the children to their various places of worship. (20) We are also told that this friendly arrangement continued harmoniously for around 25 years. (21) However, what appears to be the first indicator of schism occurred in 1834 when the church party is said to have ‘built a school close by the church for their own scholars.’ (22) Whether this was the cause of division or merely symptomatic of it remains unclear. What is clear is that by creating its own Sunday school, the established church had tacitly withdrawn any support it might have had for the New School project. When we consider the relatively modest amount contributed by St Peters in 1809, it may be reasonable to speculate that the church had been less than enthusiastic about the enterprise from the beginning.

It becomes evident that the ownership of the school had become a source of contention when, in 1835, a deed was enrolled in the Court of Chancery and the following people were appointed trustees:

Both schools were also utilised for township meetings. PH Booth tells us that ‘previous to 1809 the two rooms in Gildersome Town Hall [the Old Town School] which stood on the waste beyond the church were used for meetings of the officials of the Township: the overseers, the surveyors and the constable.’ (15) Booth also confirms that the school built at Town End in 1810 was utilised as a committee room by the township when he states that a public meeting had been held at the New School in 1818 to nominate a ‘committee to assist and advise the Overseers of the Poor.’ (16) A meeting in the following month at the same venue established the rules and regulations under which the committee would proceed with their duties. Booth goes on to state that in 1863 a Township meeting was held at the Old Town School concerning the proposed building of the Mount Zion chapel. Booth is clearly differentiating between the New School and the Old School, so we might safely infer that town meetings were held at both venues. He later states that in 1822 the committee resolved to purchase six arm chairs and a deal table for the use of the Town and the Committee’ and that these items were ‘evidently for the [Old] Town’s School which stood on the Green opposite Moorfield House.’ (17) It is unfortunate, however, that Booth neglects to disclose exactly what ‘evidence’ had enabled him to reach his conclusion. Clearly both schools had been used as committee rooms and it may be that in 1822 township meetings were taking place in the Old Town School. However, given the proximity of the date of the recorded meeting in 1818 and that of the purchase, along with the fact that he neglects to provide any supporting evidence, it may be that Booth is making something of an assumption. One might equally assume that a venue in use for over fifty years would already have a table and chairs for the committee, while a relatively new building might not? While it is indisputable that the table and chairs had been acquired for the use of the committee, the dates suggest that they might equally have been purchased to facilitate the committee meetings at the New School.

Alongside township business, the New School building was also utilised during the week as a meeting room by various benefit societies; the Mechanics Institute, for example, used one of the classrooms as a “newsroom”. Additionally, in 1843, a number of lectures were delivered at the New School, including a demonstration of “mesmero-phrenology” which appears to have particularly impressed the audience when a volunteer subject almost fell off the stage during the performance. Another lecture, taking as its subject the “millennium,” failed to excite quite the same level of enthusiasm; the Leeds Times complained that ‘the lecture and discussion [had] only made the darkness on this subject more visible”. (18) In the 1830s, the New School building was also utilised as a fee-paying day school under the tutelage of a person by the name of Samuel Firth, of which more will be revealed below.

The New School’s inception had begun as an amicable enterprise supported by a cross section of the township’s religious institutions and the subscriptions made in 1809 had been drawn from representatives of Gildersome’s various places of worship. Inevitably, some denominations subscribed more than others. The weightiest contribution came from those of the Baptist persuasion whose efforts raised in excess of £100. The Society of Friends donated over £60 and the Methodists a rather modest £16. Bringing up the rear were those from St Peter’s Church whose contribution amounted to a less than impressive £8.10. (19)

Perhaps inevitably, these figures would become an element of contention when what appears to have begun as an amicable cross-denominational enterprise appears to have collapsed into bitter dispute and acrimony.

We are told that the Sunday school was originally staffed by volunteer teachers of several denominations who, at the conclusion of lessons, conducted the children to their various places of worship. (20) We are also told that this friendly arrangement continued harmoniously for around 25 years. (21) However, what appears to be the first indicator of schism occurred in 1834 when the church party is said to have ‘built a school close by the church for their own scholars.’ (22) Whether this was the cause of division or merely symptomatic of it remains unclear. What is clear is that by creating its own Sunday school, the established church had tacitly withdrawn any support it might have had for the New School project. When we consider the relatively modest amount contributed by St Peters in 1809, it may be reasonable to speculate that the church had been less than enthusiastic about the enterprise from the beginning.

It becomes evident that the ownership of the school had become a source of contention when, in 1835, a deed was enrolled in the Court of Chancery and the following people were appointed trustees:

|

John Bilbrough

James Bilbrough Edward Buttrey Joseph Brooks Bilbrough Brooks Priestley Bilbrough John Booth |

George Booth

Joseph Crowther Samuel Smith George Holliday Caleb Crowther |

What had actually driven the appointment of trustees is unclear. However, a public notice was served in November 1835 with regard to a pending Act of Parliament to enclose the commons, wastes and waste grounds in the Township of Gildersome. (23) It may, therefore, have been in response to concern about establishing the legal ownership of a property that had been built on Gildersome’s manorial waste before the enclosures took effect. This concern is reflected in a diary entry describing a contemporary situation in Morley in which a chapel had been built on Land belonging to Lord Dartmouth in 1765. In 1833, the Dartmouth estate had demanded a rent of £50 per annum, which the chapelgoers refused to pay and, consequently, were given notice to quit. The diarist poses the question as to whether the same fate might befall the New School and concludes that it probably would. (24) Whether the appointment of trustees would have prevented a similar outcome is unclear, though the establishment of ownership is likely to have strengthened a legal challenge should this have been necessary. Given that eight of the New School’s trustees have associations with the Baptist chapel, it appears that the Baptists were foremost in ascertaining ownership and control of the school.

The dispute that had been simmering reached crisis point in 1836 when Samuel Firth, who for several years had been running a day school in one of the classrooms, was given notice to quit by the recently appointed trustees. This he refused to do. It becomes evident that Firth was not without support, as it appears that during the week beginning the 7th of February 1836, a group comprising of J. Elam, Daniel Gilpin, Matthew Stephenson and the overseers (all churchmen) took it upon themselves to fasten up both doors of the New School. Presumably, this was done to deny access to the Sunday school and consolidate Mr Firth’s position as tenant. However, this manoeuvre was met with a proportionately mature response. With the Sunday scholars unable to access their customary lessons, the doors were broken open by a nonconformist group led by James Bilbrough (a Baptist) and Firth’s desk was summarily thrown into the street.

On the 18th of February 1836, the New School hosted a Town meeting, seemingly instigated by the church party, which appointed Elam, Gilpin and Stephenson along with Jeremiah Stead to serve as a committee in order to deliberate on preserving the rights of the school (and presumably denying the rights of the Baptists). Following which, in April a vestry meeting was held in order to ascertain whether the ‘New School belongs to the subscribers or to the Town.’ (25) It is evident that control of the school is in dispute, with the subscribers (mainly nonconformists) being challenged by the Town (i.e. the church). The meeting was scheduled for 11am on a working day, a point of contention for the opposition who felt that this had been done to prevent their attendance. Whether this claim was justified or not, the timing of the meeting did little to persuade neutrals that the dispute would be conducted in a spirit of cordiality.

Any possibility of cooperation had already evaporated, however, when, in March of 1836, a trial had been held at York. The action brought was for trespass, with Samuel Firth as plaintiff and James Bilbrough, John Booth and John Harrison the defendants. At the outcome “the jury found a verdict for the plaintiff, damages one shilling.’ (26) Though Firth won his case and his opponents were ordered to pay the costs, the fact that the damages were set so low suggests that neither side had produced a particularly compelling argument. The Bilbrough chronicler summarises the outcome as follows: ‘the Baptists or Liberal Party were properly in possession but [had taken] an unlawful way of getting rid of the tenant so had to pay all the expenses of the trial.’ (27)

While the trial had clearly focused on Firth’s ejection, when we take account of the fact that the defendants took the trouble to carry a heavy wooden board bearing the names of the original subscribers to the trial at York by stagecoach, it becomes even more evident that the underlying dispute centred on the ownership of the school. In an altercation that continued well beyond the trial, the Baptists made considerable consequence of their having provided the largest subscription and clearly felt that this had merited a proportionate influence on the way the school was to be conducted. It is also apparent that the established church had become keen to maintain its influence in a project it had previously shown little interest in when a nonconformist complains that ‘three individuals in this village have lately become so much in love with this school that they are almost moving heaven and earth to get a share in it, although not one of them gave a single farthing towards the building of it.’ (28) There can be little doubt that one of the individuals alluded to was John Elam, the Churchwarden of St Peter’s who wrote several letters to the Leeds Mercury challenging that (Liberal) newspaper’s reporting of the court case. The Mercury’s reportage had made explicit reference to ‘Gildersome’s Tory churchmen [being] in pursuance of an endeavour to obtain the undivided control of [the New School].’ (29)

It has often been opined that possession amounts to nine tenths of the law and it seems that the Baptists eventually emerged from the dispute in possession of the field. A Sunday school continued to be conducted at the New School for some 25 years until, in 1860, a more commodious building was erected close to the Baptist chapel. We are told that the School on the Green continued to be used for several purposes until, in 1876, it was let to the Wesleyans as a Sunday school for a nominal rent of one shilling per annum. This arrangement continued until 1884. In 1886, a new deed was drawn up and new trustees appointed. From which time, the school remained in the possession of the Wesleyans until a new Sunday school building was attached to the Wesleyan chapel in 1904. (30)

By 1904, the township boasted no less than three recently built elementary schools. Added to which, Sunday schools had been established at all of the township’s nonconformist chapels. The New Sunday School on the Green had become the Old Sunday School and surplus to requirements. Booth tells us that it was eventually ‘sold by the trustees, with the consent of the Board of Education, and the money realised invested for the benefit of education in Gildersome.’ (31) A deed registered in 1906 by the County Council of the West Riding established a charitable fund under the trusteeship of the Board of Education. What then became known as the Old Sunday School Foundation provided financial support for scholars whose parents were ‘bona fide resident in the Urban District of Gildersome’. (32) The Foundation provided assistance with the purchase of books, instruments and travelling expenses for scholars attending ‘evening schools, day or evening classes, or courses of instruction approved by the trustees.’ (33) Awards were distributed yearly. In November, 1933, for example, a committee comprising Mr Troughton, Mr Dixon, the Rev. F. Archer, and Mr Grayshon met at Street Lane School and awarded a total of nine pounds and ten shillings to nine Gildersome scholars.

In 1908, what was by this time the Old Sunday School House was sold by the County Council of the West Riding and converted into two cottages, which became the subject of a clearance order in 1960. (34)

The dispute that had been simmering reached crisis point in 1836 when Samuel Firth, who for several years had been running a day school in one of the classrooms, was given notice to quit by the recently appointed trustees. This he refused to do. It becomes evident that Firth was not without support, as it appears that during the week beginning the 7th of February 1836, a group comprising of J. Elam, Daniel Gilpin, Matthew Stephenson and the overseers (all churchmen) took it upon themselves to fasten up both doors of the New School. Presumably, this was done to deny access to the Sunday school and consolidate Mr Firth’s position as tenant. However, this manoeuvre was met with a proportionately mature response. With the Sunday scholars unable to access their customary lessons, the doors were broken open by a nonconformist group led by James Bilbrough (a Baptist) and Firth’s desk was summarily thrown into the street.

On the 18th of February 1836, the New School hosted a Town meeting, seemingly instigated by the church party, which appointed Elam, Gilpin and Stephenson along with Jeremiah Stead to serve as a committee in order to deliberate on preserving the rights of the school (and presumably denying the rights of the Baptists). Following which, in April a vestry meeting was held in order to ascertain whether the ‘New School belongs to the subscribers or to the Town.’ (25) It is evident that control of the school is in dispute, with the subscribers (mainly nonconformists) being challenged by the Town (i.e. the church). The meeting was scheduled for 11am on a working day, a point of contention for the opposition who felt that this had been done to prevent their attendance. Whether this claim was justified or not, the timing of the meeting did little to persuade neutrals that the dispute would be conducted in a spirit of cordiality.

Any possibility of cooperation had already evaporated, however, when, in March of 1836, a trial had been held at York. The action brought was for trespass, with Samuel Firth as plaintiff and James Bilbrough, John Booth and John Harrison the defendants. At the outcome “the jury found a verdict for the plaintiff, damages one shilling.’ (26) Though Firth won his case and his opponents were ordered to pay the costs, the fact that the damages were set so low suggests that neither side had produced a particularly compelling argument. The Bilbrough chronicler summarises the outcome as follows: ‘the Baptists or Liberal Party were properly in possession but [had taken] an unlawful way of getting rid of the tenant so had to pay all the expenses of the trial.’ (27)

While the trial had clearly focused on Firth’s ejection, when we take account of the fact that the defendants took the trouble to carry a heavy wooden board bearing the names of the original subscribers to the trial at York by stagecoach, it becomes even more evident that the underlying dispute centred on the ownership of the school. In an altercation that continued well beyond the trial, the Baptists made considerable consequence of their having provided the largest subscription and clearly felt that this had merited a proportionate influence on the way the school was to be conducted. It is also apparent that the established church had become keen to maintain its influence in a project it had previously shown little interest in when a nonconformist complains that ‘three individuals in this village have lately become so much in love with this school that they are almost moving heaven and earth to get a share in it, although not one of them gave a single farthing towards the building of it.’ (28) There can be little doubt that one of the individuals alluded to was John Elam, the Churchwarden of St Peter’s who wrote several letters to the Leeds Mercury challenging that (Liberal) newspaper’s reporting of the court case. The Mercury’s reportage had made explicit reference to ‘Gildersome’s Tory churchmen [being] in pursuance of an endeavour to obtain the undivided control of [the New School].’ (29)

It has often been opined that possession amounts to nine tenths of the law and it seems that the Baptists eventually emerged from the dispute in possession of the field. A Sunday school continued to be conducted at the New School for some 25 years until, in 1860, a more commodious building was erected close to the Baptist chapel. We are told that the School on the Green continued to be used for several purposes until, in 1876, it was let to the Wesleyans as a Sunday school for a nominal rent of one shilling per annum. This arrangement continued until 1884. In 1886, a new deed was drawn up and new trustees appointed. From which time, the school remained in the possession of the Wesleyans until a new Sunday school building was attached to the Wesleyan chapel in 1904. (30)

By 1904, the township boasted no less than three recently built elementary schools. Added to which, Sunday schools had been established at all of the township’s nonconformist chapels. The New Sunday School on the Green had become the Old Sunday School and surplus to requirements. Booth tells us that it was eventually ‘sold by the trustees, with the consent of the Board of Education, and the money realised invested for the benefit of education in Gildersome.’ (31) A deed registered in 1906 by the County Council of the West Riding established a charitable fund under the trusteeship of the Board of Education. What then became known as the Old Sunday School Foundation provided financial support for scholars whose parents were ‘bona fide resident in the Urban District of Gildersome’. (32) The Foundation provided assistance with the purchase of books, instruments and travelling expenses for scholars attending ‘evening schools, day or evening classes, or courses of instruction approved by the trustees.’ (33) Awards were distributed yearly. In November, 1933, for example, a committee comprising Mr Troughton, Mr Dixon, the Rev. F. Archer, and Mr Grayshon met at Street Lane School and awarded a total of nine pounds and ten shillings to nine Gildersome scholars.

In 1908, what was by this time the Old Sunday School House was sold by the County Council of the West Riding and converted into two cottages, which became the subject of a clearance order in 1960. (34)

The single-storey building within the red oval to the right of Grayson’s Handy Shop (Formerly the Miners' Arms) is one of only two other known photographic records of the New School on the Green. Taken around 1960.

1 Gillard D (2018) Education in England: a history, WWW.educationengland.org.uk/history

2 Crichbaptist.org.

3 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

4 Bronte, C. (1848) 1998. Smith, M & Rosengarten, H, editors. Shirley, Oxford: University Press, p 304.

5 Tevelyan, GM. (1942) 1964. Illustrated English Social History: Volume Four, Harmondsworth: Penguin, p 217.

6 WYAS. Registry of Deeds.

7 By the late 1850s, a school was being conducted by William Whitaker, probably at his home on the Little Green. It is possible that this is the

other day school alluded to by the Gazette in 1847.

8 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

9 Ibid.

10 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

11 WYAS. Registry of Deeds.

12 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

13 History of the Baptist Church at Gildersome, Leeds: Walker & Laycock, p 28. The fees would have been very moderate, though beyond the

reach of many.

14 Given the financial pressures on families surviving on subsistence wages, there is a certain irony in that government restrictions on children

working in factories must have resulted in children excluded from the factory seeking employment in worse conditions underground.

15 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family.

16 Ibid.

17 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family.

18 Leeds Times, 1843. It is possible that the “Millenium” lecture was delivered in the Old Methodist Schoolrooms in the Bottoms. However, it

provides a fascinating insight into the educational discussions circulating at the time.

19 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

20 Ibid.

21 History of the Baptist Church at Gildersome, Leeds: Walker & Laycock, p 28.

22 Ibid. Some sources claim that the church school opened in 1837 and others in 1840.

23 Leeds Intelligencer, 1835.

24 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

25 Ibid.

26 Leeds Intelligencer, 1837.

27 Chronicles of my Ancestors, p222.

28 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

29 Leeds Intelligencer, March, 1837. The owner of the Leeds Mercury, Edward Baines, was a staunch nonconformist.

30 Yorkshire Post, 1904.

31 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family, p.68.

32 WYAS, Registry of Deeds.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

2 Crichbaptist.org.

3 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

4 Bronte, C. (1848) 1998. Smith, M & Rosengarten, H, editors. Shirley, Oxford: University Press, p 304.

5 Tevelyan, GM. (1942) 1964. Illustrated English Social History: Volume Four, Harmondsworth: Penguin, p 217.

6 WYAS. Registry of Deeds.

7 By the late 1850s, a school was being conducted by William Whitaker, probably at his home on the Little Green. It is possible that this is the

other day school alluded to by the Gazette in 1847.

8 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

9 Ibid.

10 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

11 WYAS. Registry of Deeds.

12 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

13 History of the Baptist Church at Gildersome, Leeds: Walker & Laycock, p 28. The fees would have been very moderate, though beyond the

reach of many.

14 Given the financial pressures on families surviving on subsistence wages, there is a certain irony in that government restrictions on children

working in factories must have resulted in children excluded from the factory seeking employment in worse conditions underground.

15 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family.

16 Ibid.

17 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family.

18 Leeds Times, 1843. It is possible that the “Millenium” lecture was delivered in the Old Methodist Schoolrooms in the Bottoms. However, it

provides a fascinating insight into the educational discussions circulating at the time.

19 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

20 Ibid.

21 History of the Baptist Church at Gildersome, Leeds: Walker & Laycock, p 28.

22 Ibid. Some sources claim that the church school opened in 1837 and others in 1840.

23 Leeds Intelligencer, 1835.

24 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

25 Ibid.

26 Leeds Intelligencer, 1837.

27 Chronicles of my Ancestors, p222.

28 WYAS, Bilbrough, Town and Wright Families, Records.

29 Leeds Intelligencer, March, 1837. The owner of the Leeds Mercury, Edward Baines, was a staunch nonconformist.

30 Yorkshire Post, 1904.

31 Booth, PH. 1920. History of Gildersome and the Booth Family, p.68.

32 WYAS, Registry of Deeds.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.