|

Health Lectures, Monitors and Zeppelins:

Gildersome’s second National (Church of England) School. |

by: Andrew Bedford © 2019 |

The newly erected National School circa 1897. The builder’s shed is still in position to the right. The single-storey building behind the shed is almost certainly the Old Town School.

For further reading about Gildersome's schools go to: The Old National School

The New School on the Green

Gildersome's Board Schools

The New School on the Green

Gildersome's Board Schools

The Education Act of 1870 required that every child between the ages of 5 and 13 should be provided with elementary education, establishing local school boards to ensure attendance. Gildersome was among the first to appoint a school board (1872) and in 1874 two Board Schools were established in the Township (Street Lane and Gelderd Road). Prior to the School Boards, the Church of England had been heavily involved in education provision and church (or National) schools continued to receive maintenance grants of up to 50% of running costs after 1870. So, although it was intended to standardise elementary education, the 1870 Education Act effectively created a dual system of board and voluntary schools. Gildersome’s National School fell into the latter category and this duality of provision would be the cause of considerable rivalry.

The critical difference between a National School education and that offered by a Board School was religious instruction; this was a difference that led to a great deal of hostility in Gildersome. The National Schools were structured around religious teaching along Church of England lines, while the Board Schools took a secular approach. While religious education was taught in Board Schools, the teaching was nonconformist in principle and never specific to any particular religious organisation. It becomes evident, then, that the competition for scholars was also a competition for future worshippers.

After 1874, Gildersome’s first National School found itself competing for scholars with two larger schools offering up-to-date facilities. According to an assessment made in 1877, the newly erected Board Schools at Street Lane and Gelderd Road were able to accommodate 300 and 200 scholars respectively, while the existing National School building was only able to accommodate 136. (1) It is also worth noting that the latter figure appears somewhat optimistic given the size of the building; it is not beyond possibility that these figures take into account all children enrolled, rather than those in regular attendance. However, it is indisputable that the accommodation provided by the first National School had become inadequate and new premises were required in order to meet the challenges posed by the competition.

This was a competition engendered by not only religious but also political and philosophical differences. Supporters of the Board Schools were, for the most part, politically Liberal and religiously nonconformist, motivated by an underlying belief in education for the masses. On the other hand, the National Schools were championed by the Conservative Party and the Church of England, both of which were generally suspicious of mass education. The supporters of Board Schools advocated education that was free at the point of delivery, with funding drawn from a local “school rate.” From a Conservative/Church of England perspective, it was popularly assumed that free education would undermine parental responsibility and therefore be “degrading” to the working classes. (2) In the event, a compromise was arrived at in which nominal school fees would continue, though these could be waived by the school boards if parents were proved to be in financial hardship. Because the 1870s were a time of considerable deprivation in the Gildersome area, this would have been seen as a considerable benefit to parents in straitened circumstances. It might be suggested, then, that it was the success of the new Board Schools that compelled the Church of England to build the second National School in Gildersome.

When the church eventually proposed to build a new school some 50 yards away from the old one, what had been a competitive situation degenerated into outright animosity. The site on which the new premises were to be erected had for some time been a considerable source of irritation to the nonconformists. The Bolton Hargrave Charity was financed by rent from three cottages standing on the site proposed for the new school. The charity was managed by the churchwardens and, from 1750, had enabled ten boys from poor families to be educated free of charge. This provision was initially facilitated by the Old Town School and later by the first National School. When it was proposed to demolish the cottages to make way for and contribute to the cost and maintenance of a new National School, the nonconformist factions went onto the attack. A public meeting was convened in order to consider the future regulation of the Charity of Bolton Hargrave. At the meeting, Mr Samuel Crowther (of Harthill House) voiced nonconformist concerns about the administration of the charity, demanding that an investigation should be made into ‘the way in which the charity has been dispensed.’ PH Booth (of Moorfield House) was more forthright in his criticism: he complained that money intended for boys from the poorest families in Gildersome had, to his certain knowledge, been awarded to the son of an overseer, the son of a guardian and even the son of the schoolmaster. (3) However, despite the nonconformist’s protestations and allegations, the Charity Commission sided with the church, directing that the charity ‘shall be applied in or towards the erection of new buildings’ for the National School. (4)

The 1902 Education Act effectively placed responsibility for and control of elementary education in the hands of county and borough councils. The newly commissioned Local Education Authorities effectively replaced the local school boards. In Gildersome, this meant that the two schools previously managed by the Gildersome School Board (Street Lane and Gelderd Road) would now be directly controlled by the LEA. The Act also meant that Gildersome’s National School could also apply to be governed by the same authority as its nonconformist neighbours. Doing so offered considerable financial support to what was proving to be a very expensive undertaking for the church. In due course, the managers of the National School at Gildersome: the Reverend David Cowling, Cyrus Holiday (of Park House) and William Bedford (of Turton Hall) applied to the Board of Education for an ‘order constituting a body of Foundation Managers under the Education Act of 1902’. (5) The trustees of the school were listed as follows: Henry Holiday (Gildersome), George Troughton Bedford (Morley), Robert Hudson (Headingley), George Hudson (Drighlington) and Matthew Stephenson (Harrogate). Adopting the 1902 Act meant that Gildersome’s National School would receive maintenance support from the newly formed LEA, relieving a considerable financial burden on the church. It has been suggested that the Church of England’s primary objective in adopting the Act for its National Schools was to derive maximum benefit from public subsidy while continuing to manage its own affairs as far as possible. (6)

What might be seen as a potential point of conflict in the Church’s position led to something of a crisis in 1904 when the District Sub-Committee of the Local Education Authority sanctioned a series of public health lectures to be held in Gildersome. Because its main room had the capacity to accommodate up to 600 people, the National School was appointed as the venue. It seems that the church had fallen victim to its own success by creating a larger and better-appointed facility than that offered by its opponents. However that may be, the directive was seen by the school managers as an unjustified interference. As far as they were concerned, the new National School was only obligated to the LEA during school hours. The Reverend David Cowling responded as follows:

The critical difference between a National School education and that offered by a Board School was religious instruction; this was a difference that led to a great deal of hostility in Gildersome. The National Schools were structured around religious teaching along Church of England lines, while the Board Schools took a secular approach. While religious education was taught in Board Schools, the teaching was nonconformist in principle and never specific to any particular religious organisation. It becomes evident, then, that the competition for scholars was also a competition for future worshippers.

After 1874, Gildersome’s first National School found itself competing for scholars with two larger schools offering up-to-date facilities. According to an assessment made in 1877, the newly erected Board Schools at Street Lane and Gelderd Road were able to accommodate 300 and 200 scholars respectively, while the existing National School building was only able to accommodate 136. (1) It is also worth noting that the latter figure appears somewhat optimistic given the size of the building; it is not beyond possibility that these figures take into account all children enrolled, rather than those in regular attendance. However, it is indisputable that the accommodation provided by the first National School had become inadequate and new premises were required in order to meet the challenges posed by the competition.

This was a competition engendered by not only religious but also political and philosophical differences. Supporters of the Board Schools were, for the most part, politically Liberal and religiously nonconformist, motivated by an underlying belief in education for the masses. On the other hand, the National Schools were championed by the Conservative Party and the Church of England, both of which were generally suspicious of mass education. The supporters of Board Schools advocated education that was free at the point of delivery, with funding drawn from a local “school rate.” From a Conservative/Church of England perspective, it was popularly assumed that free education would undermine parental responsibility and therefore be “degrading” to the working classes. (2) In the event, a compromise was arrived at in which nominal school fees would continue, though these could be waived by the school boards if parents were proved to be in financial hardship. Because the 1870s were a time of considerable deprivation in the Gildersome area, this would have been seen as a considerable benefit to parents in straitened circumstances. It might be suggested, then, that it was the success of the new Board Schools that compelled the Church of England to build the second National School in Gildersome.

When the church eventually proposed to build a new school some 50 yards away from the old one, what had been a competitive situation degenerated into outright animosity. The site on which the new premises were to be erected had for some time been a considerable source of irritation to the nonconformists. The Bolton Hargrave Charity was financed by rent from three cottages standing on the site proposed for the new school. The charity was managed by the churchwardens and, from 1750, had enabled ten boys from poor families to be educated free of charge. This provision was initially facilitated by the Old Town School and later by the first National School. When it was proposed to demolish the cottages to make way for and contribute to the cost and maintenance of a new National School, the nonconformist factions went onto the attack. A public meeting was convened in order to consider the future regulation of the Charity of Bolton Hargrave. At the meeting, Mr Samuel Crowther (of Harthill House) voiced nonconformist concerns about the administration of the charity, demanding that an investigation should be made into ‘the way in which the charity has been dispensed.’ PH Booth (of Moorfield House) was more forthright in his criticism: he complained that money intended for boys from the poorest families in Gildersome had, to his certain knowledge, been awarded to the son of an overseer, the son of a guardian and even the son of the schoolmaster. (3) However, despite the nonconformist’s protestations and allegations, the Charity Commission sided with the church, directing that the charity ‘shall be applied in or towards the erection of new buildings’ for the National School. (4)

The 1902 Education Act effectively placed responsibility for and control of elementary education in the hands of county and borough councils. The newly commissioned Local Education Authorities effectively replaced the local school boards. In Gildersome, this meant that the two schools previously managed by the Gildersome School Board (Street Lane and Gelderd Road) would now be directly controlled by the LEA. The Act also meant that Gildersome’s National School could also apply to be governed by the same authority as its nonconformist neighbours. Doing so offered considerable financial support to what was proving to be a very expensive undertaking for the church. In due course, the managers of the National School at Gildersome: the Reverend David Cowling, Cyrus Holiday (of Park House) and William Bedford (of Turton Hall) applied to the Board of Education for an ‘order constituting a body of Foundation Managers under the Education Act of 1902’. (5) The trustees of the school were listed as follows: Henry Holiday (Gildersome), George Troughton Bedford (Morley), Robert Hudson (Headingley), George Hudson (Drighlington) and Matthew Stephenson (Harrogate). Adopting the 1902 Act meant that Gildersome’s National School would receive maintenance support from the newly formed LEA, relieving a considerable financial burden on the church. It has been suggested that the Church of England’s primary objective in adopting the Act for its National Schools was to derive maximum benefit from public subsidy while continuing to manage its own affairs as far as possible. (6)

What might be seen as a potential point of conflict in the Church’s position led to something of a crisis in 1904 when the District Sub-Committee of the Local Education Authority sanctioned a series of public health lectures to be held in Gildersome. Because its main room had the capacity to accommodate up to 600 people, the National School was appointed as the venue. It seems that the church had fallen victim to its own success by creating a larger and better-appointed facility than that offered by its opponents. However that may be, the directive was seen by the school managers as an unjustified interference. As far as they were concerned, the new National School was only obligated to the LEA during school hours. The Reverend David Cowling responded as follows:

In reply to your letter dated 22nd instant stating that the District Sub-Committee have arranged to use the Gildersome National School for a course of six health lectures, I beg to say in the name of the Managers that your Committee have no jurisdiction whatever over our schools out of school hours … The lectures, therefore, which your Committee have taken upon themselves to arrange without any consultation or communication with the Managers will not be permitted in the Church School unless the sum of 15/- per lecture be paid to the Managers in advance. (7)

Cowling made it clear that if the LEA wished to use the National School for the lectures, it was going to have to meet the extra cost in cleaning etc. that staging the event would incur. Cowling and the school managers also argued that if the Local Authority wished to hold a series of lectures, these could be readily facilitated by the premises at Street Lane and Gelderd Road. The LEA countered by stating that neither of those schools had sufficient capacity to hold the lectures and insisted that the National School be compliant with its wishes.

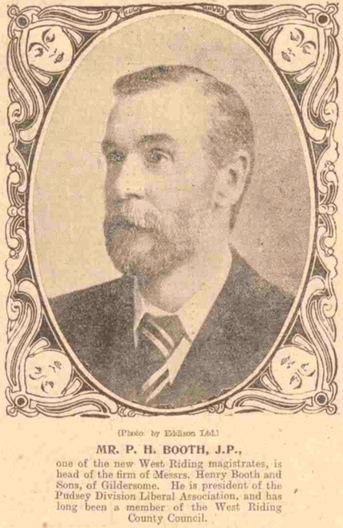

Above left: the Bishop of Wakefield who directed the National School’s strategy from his armchair at the Athenaeum Club, Pall Mall. Above right: Philip Henry Booth a key protagonist on the nonconformist side.

With neither side willing to give way, the arguments passed back and forth, with the Educational Sub-Committee taking instruction from the LEA and Department of Education, while Cowling and the school managers took their instructions from the Bishop of Wakefield. The argument in the interests of the established church was presented by the Reverend Cowling. On the other side of the divide, the argument was taken up by Philip Henry Booth, a prominent Baptist, former member of the now defunct Gildersome School Board and a vociferous supporter of secular education. When the LEA threatened to withdraw funding from the National School unless the churchmen agreed to facilitate the lectures, the Reverend Cowling was quick to draw attention to the source of that threat:

The [school] managers cannot help noticing that it is County Councillor P.H. Booth who moves the rider threatening to cease maintenance of our school because we have not forgotten that eight years ago he did everything in his power to prevent the erection of the school; and only eight months ago, when I attempted to discuss with him the County Council’s proposal of 2/6 per child in average attendance as a condition of transference of our schools, he emphatically declared that although our schools are new and admittedly up to date he would rather see them closed than vote a penny. (8)

In due course, however, Cowling and the managers were persuaded to back down. On the 27th of October a telegram was received at Gildersome Post Office advising the following compromise:

Cowling Vicarage Gildersome. Strongly urge reserving right and opening school. Bishop. (9)

In essence, the Bishop’s advice was to allow the lectures to take place with the reservation that were the first lecture to attract fewer than one hundred people, the remaining lectures would be held at one of the smaller venues. This compromise enabled the National School’s managers to present the appearance of having had the final say, while at the same time ensuring that the school’s LEA funding would not be withdrawn. In addition, they were confident that the audience for the first lecture would fall well short of one hundred people. In the event, the audience was well in excess of that figure. The church party, however, were not slow to point an accusing finger at the nonconformists who, they alleged, had used subterfuge to ensure that the lecture was well attended. Cowling complained that the audience had been unfairly supplemented by people who had simply gone along in expectation of a “disturbance”, along with a large number of Board School children who had been offered shillings for the best essays on the subject of the lecture. (10)

While the lecture situation had arrived at a resolution by way of a rather reluctant compromise, the animosity rumbled on. The School Managers’ grievances regarding the Education Authority’s insistence on utilising the building out of school hours rebounded spectacularly when their own extra-curricular activities came under scrutiny. Having demanded financial compensation for the use of the school out of hours with regard to the lectures, the managers were nonplussed when the Education Authority reciprocated with counter demands for extra-curricular activities being run by the managers. In July 1905 the Education Authority instructed the managers to repay two sevenths of the annual cost of heating, etc. to the amount of £1 14s 1d. However, an earlier demand for reimbursement of the cleaner’s salary (£7 17s 9d) was withdrawn. In a separate issue regarding the teaching of religious instruction, the headmaster’s (Albert Jowett) salary was reduced from £150 per annum to £144, an indication, perhaps, of the Education Authority’s insistence that if religious instruction were to be provided at the National School, it would not be at the ratepayers’ expense.

The friction between school managers and the Education Authority continued. In 1905 a school inspection resulted in the Education Authority drawing up a list of required repairs and improvements:

While the lecture situation had arrived at a resolution by way of a rather reluctant compromise, the animosity rumbled on. The School Managers’ grievances regarding the Education Authority’s insistence on utilising the building out of school hours rebounded spectacularly when their own extra-curricular activities came under scrutiny. Having demanded financial compensation for the use of the school out of hours with regard to the lectures, the managers were nonplussed when the Education Authority reciprocated with counter demands for extra-curricular activities being run by the managers. In July 1905 the Education Authority instructed the managers to repay two sevenths of the annual cost of heating, etc. to the amount of £1 14s 1d. However, an earlier demand for reimbursement of the cleaner’s salary (£7 17s 9d) was withdrawn. In a separate issue regarding the teaching of religious instruction, the headmaster’s (Albert Jowett) salary was reduced from £150 per annum to £144, an indication, perhaps, of the Education Authority’s insistence that if religious instruction were to be provided at the National School, it would not be at the ratepayers’ expense.

The friction between school managers and the Education Authority continued. In 1905 a school inspection resulted in the Education Authority drawing up a list of required repairs and improvements:

1. Partition the main room by means of a movable partition cutting off about one third of its length.

2. Improve the playground so as to secure a hard and permanent surface free from dust and usable in all

states of weather.

3. Drain the lower part of the girls’ playground and free the gullies from stones and loose soil.

4. Deepen the channel of the urinal and provide partitions on the boys’ side.

5. Attend to the floor of the closets so as to prevent water standing in them.

6. Improve the ashpit by making the roof slope and also repair the woodwork.

7. Replace the missing pegs in the boys’ cloakroom.

8. Improve the ventilation by re-opening the existing inlets and provide means of checking draughts.

9. Colorwash [sic] and paint the interior of the schoolrooms.

The nature of the proposed improvements suggests that these were issues outstanding from the building work undertaken in 1896/7. Clearly the LEA did not feel obliged to make a retrospective contribution toward the cost of building the school. The Education Authority also warned the Managers of Gildersome’s National School that failure to complete the required improvements by no later than the termination of the ensuing Mid-Summer holidays would result in maintenance funding being withdrawn. As there are no records to suggest that maintenance was indeed withdrawn, we must assume that the work was carried out. In fact, I can personally vouch for the existence of a partition in the school hall in the 1950s. However, I am also able to confirm that the standing water in the boys’ lavatories remained a problem.

The National School hall circa 1900. The head teacher’s desk is to the left, in front of which stand the lecterns from which monitors would have faced the scholars seated on the forms to the right. The position of the camera suggests that the partition had yet to be installed.

In order to provide elementary education at minimal cost, the National Schools had, from their inception, been run on the “monitorial” system. In this way, a single, salaried teacher was able to supervise the education of large numbers of children by appointing more able scholars (or monitors) to teach their less able classmates. In the early years of the National School system this practice had been open to considerable abuse. However, under the guidance of the Local Education Authority, the monitorial system was becoming more effectively regulated. In 1905, for example, the appointment of Alice Tordoff as monitress at the National School was sanctioned by the Education Department. Miss Tordoff was to receive a salary of £6 per annum. In the following year, Charles Beevers was employed as a monitor at the same rate of pay. A memorandum from the Education Department outlined the following requirements:

All candidates for monitorships must be free from legal obligation to attend school, and must have a bona fide intention of becoming pupil teachers. Monitors may not be employed more than half time in actual school work, and they should be given facilities for study, under the guidance of the Headteacher, with a view to their qualifying, by examination, as Pupil Teachers or as Intending Pupil Teachers.

This indicates a considerable move away from the simple exploitation of better able scholars. Monitors now had to be above the age at which they were legally obliged to attend school. The hours they were required to work were restricted and they were to be provided with appropriate guidance in their pursuit of teaching qualifications. An illustration of which is provided by a letter dated February 1906 advising that Miss Annie Holdsworth would continue in a course of instruction for pupil teachers at the Leeds Thoresby High School on a half time basis. It may also be worth noting that, with a starting salary set at less than half that of the lowest paid girls in the textile industry, the applicants are likely to have been drawn from relatively affluent backgrounds. (11)

Staff and children photographed circa 1900. Photograph courtesy of Joyce Smith

In 1902 the Gildersome’s National School was staffed as follows:

Albert Jowett, certified teacher.

Ida Troughton, ex pupil teacher.

Martha Horner, ex pupil teacher.

Caroline Scargill, pupil teacher.

Elliott Mitchell, pupil teacher.

Jane Emma Halliday, pupil teacher.

Annie Holdsworth, pupil teacher.

In 1908 Gildersome’s National School was visited by Mr F A Stannard and received the following report:

Albert Jowett, certified teacher.

Ida Troughton, ex pupil teacher.

Martha Horner, ex pupil teacher.

Caroline Scargill, pupil teacher.

Elliott Mitchell, pupil teacher.

Jane Emma Halliday, pupil teacher.

Annie Holdsworth, pupil teacher.

In 1908 Gildersome’s National School was visited by Mr F A Stannard and received the following report:

Attendance figures for the mixed school showed an average of 142 children, while the average for the infants school numbered 62.

Premises: The playgrounds remain the same; the material forming the surface does not knit together properly. Ventilation in the smaller portion of the main room is kept satisfactory by means of the opening doors; the room is draughty.

Mixed: The work presents many commendable features; the children are orderly and attentive and they are being trained to rely upon their own resources.

The scheme of instruction is sensibly devised; preparative work on the part of the teachers is quite satisfactory, and supervision is methodical and thorough.

The elementary subjects are well in hand as a rule, though reading in the first standard might be characterized by greater fluency and ease of phrasing; handwriting and composition are good, and satisfactory progress is being made in arithmetic.

The lessons in common things are well given and are intelligently apprehended by the children. In most of the oral subjects the answering is good, but a section of the third standard are not up to the general average of the school. Drawing is taught on rational lines, and a word of praise is due to smartness and precision with which the children go through their physical exercises.

Infants: the infants are happy in their school life; the teacher in charge takes pains, and the results of her work are decidedly creditable.

The children have a very good apprehension of the elements of reading, writing and number, but in the latter subject the working of mechanical exercises on slates is undesirable.

The recreative side of the work is well cared for and the children respond freely. (12)

The mention of a “smaller portion of the main room” suggests that the partition has been installed, though it remains evident that earlier issues with the playground (see above) had still not been rectified. It also appears that the installation of a partition had created further problems with ventilation. That the inspection had taken place at all suggests that, despite previous warnings, the school continued to be maintained by the Education Authority. It is noticeable, however, that on the academic side the report shows a marked improvement from the appraisals given to the first National School in the 1840s.

In 1916, the advent of World War 1 and in particular the Zeppelin raids of the previous year, led the managers of the National School to take out insurance against “damage from aircraft” and to the purchase of six fire extinguishers. (13) Happily, the Kaiser’s anticipated attack on Gildersome failed to materialise, the extinguishers don’t appear to have been called upon and the insurance went unclaimed.

The school logbook provides an insight into the rigidity of contemporary teaching methods. Before the commencement of writing lessons, a systematic Pen Drill had to be practised as follows:

In 1916, the advent of World War 1 and in particular the Zeppelin raids of the previous year, led the managers of the National School to take out insurance against “damage from aircraft” and to the purchase of six fire extinguishers. (13) Happily, the Kaiser’s anticipated attack on Gildersome failed to materialise, the extinguishers don’t appear to have been called upon and the insurance went unclaimed.

The school logbook provides an insight into the rigidity of contemporary teaching methods. Before the commencement of writing lessons, a systematic Pen Drill had to be practised as follows:

“Attention.” Children should sit to attention; arms behind, feet together and looking directly at the teacher.

“Ready.” Papers to be placed to the right of the scholar as explained (arms brought smartly behind

afterwards.

“Left.” Put the left fore arm on the paper.

“Pen.” Right hand to seize the pen in the groove at the top of the desk smartly.

“Position” or “Show.” Place right hand on paper, as explained.

Note:- The teacher will stand in front of the class and make sure that all pens are held in exactly

uniform way.

“Write.” Dip the pen in the ink and commence writing.

Happily, by the time I was learning to write at the same establishment, military precision had been dropped from the syllabus. Though, I do recall that those of us not yet in possession of a fountain pen had to do the best we could with one provided by the school. Basically, this was a stick with a steel nib at the end that dribbled ink all over the place and it is not beyond probability that this was the same equipment used in the pen drill. If so, my sincere condolences to all involved!

Mrs Leathley’s class circa 1959. The form on which some of the girls are seated is very likely to be one of those on the photograph of the school hall above. Note the studious young man, front row, far right, with the dubious taste in knitwear.

The political intrigue and sectarian squabbling outlined above will probably come as something of a surprise to those readers who, like me, attended the Church School at Gildersome. At that time there was no sense of competition with the schools at Street Lane and Gelderd Road – they were just the other schools. We shared sports facilities, such as they were, and even combined to create football and cricket teams. When I was at the Church School, the activities of “monitors” were restricted to filling inkwells and handing out bottles of milk, though the more reliable elements of Mrs Boddy’s “top girls” were entrusted to make coffee for the teaching staff on an old gas ring in the corner of the classroom. It seems ironic, though, that having previously withstood the threat of the Kaiser’s Zeppelins (and presumably Hitler’s Luftwaffe), the second National School building was eventually destroyed by fire in 1980. Even so, the school continued to function, using temporary accommodation, until 1983 when the then Secretary of State for Education, Sir Keith Joseph, sealed its fate by refusing to sanction the rebuilding work. There is, therefore, a further irony in that a school opened within a context of political intrigue at a local level should finally be closed by a decision motivated by national politics. Perhaps a sign that Gildersome was moving up in the world?

Appendix:

The Rev David Cowling was born in Farnley in 1862, the son of a tailor. In 1888 he married Annie, eldest daughter of John Helliwell of Farnley Hall. Cowling’s involvement in education was not confined to the National School movement. As well as being vicar of Gildersome, he served as the Inspector of Technical Schools for 7 years. His interest in education also extended to private tuition: an advert from the Yorkshire Post in 1904 states that the Rev D Cowling of Gildersome had vacancies for 2 or 3 more weekly boarders. He occupied the vicarage at Gildersome for 12 years before leaving in 1906 to become chaplain of the English Church at Hannover. While in Germany, Cowling also provided education for 5 or 6 resident pupils, offering “the finest educational facilities” in “purest German.” (14) At the outbreak of war in 1914, Cowling returned to England, suffering considerable personal losses. The Reverend Cowling died in 1929 aged 68 in Eppleton, County Durham.

List of head teachers of the Gildersome National School 1896-1968:

Appendix:

The Rev David Cowling was born in Farnley in 1862, the son of a tailor. In 1888 he married Annie, eldest daughter of John Helliwell of Farnley Hall. Cowling’s involvement in education was not confined to the National School movement. As well as being vicar of Gildersome, he served as the Inspector of Technical Schools for 7 years. His interest in education also extended to private tuition: an advert from the Yorkshire Post in 1904 states that the Rev D Cowling of Gildersome had vacancies for 2 or 3 more weekly boarders. He occupied the vicarage at Gildersome for 12 years before leaving in 1906 to become chaplain of the English Church at Hannover. While in Germany, Cowling also provided education for 5 or 6 resident pupils, offering “the finest educational facilities” in “purest German.” (14) At the outbreak of war in 1914, Cowling returned to England, suffering considerable personal losses. The Reverend Cowling died in 1929 aged 68 in Eppleton, County Durham.

List of head teachers of the Gildersome National School 1896-1968:

|

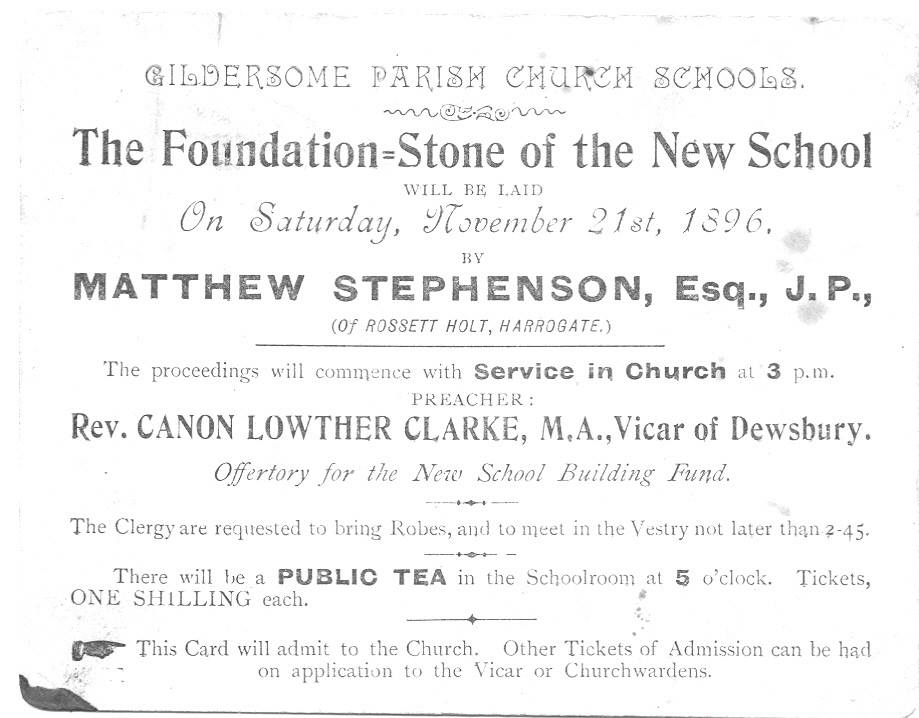

Card issued for the 1896 laying of the first foundation stone at the New School (Click image to expand)

|

Elementary schools in Gildersome (1872):

In 1872, the School Board identified seven establishments providing elementary education in Gildersome: the National School, managed and maintained by St Peter’s Church; the British School at Moorhead managed and maintained by the Baptist Chapel; Miss Mould’s school, which operated at the Friends’ Meeting House; William Whitaker’s school at Little Green; John Taylor’s school, which, according to a map presented by the board, appears to have been situated on the site of the present Wellfield Terrace; Miss Otter’s school, situated at Gildersome Street and William Lister’s school, also situated at Gildersome Street. Of these establishments, the National and British schools, were the largest. The remaining schools on the list were small scale, private enterprises. The inception of the Board Schools meant that these establishments quickly became surplus to requirements. The British School was adopted by the Gildersome School Board and briefly acted as the Moorhead Board School until the new schools were built in 1874.

In 1872, the School Board identified seven establishments providing elementary education in Gildersome: the National School, managed and maintained by St Peter’s Church; the British School at Moorhead managed and maintained by the Baptist Chapel; Miss Mould’s school, which operated at the Friends’ Meeting House; William Whitaker’s school at Little Green; John Taylor’s school, which, according to a map presented by the board, appears to have been situated on the site of the present Wellfield Terrace; Miss Otter’s school, situated at Gildersome Street and William Lister’s school, also situated at Gildersome Street. Of these establishments, the National and British schools, were the largest. The remaining schools on the list were small scale, private enterprises. The inception of the Board Schools meant that these establishments quickly became surplus to requirements. The British School was adopted by the Gildersome School Board and briefly acted as the Moorhead Board School until the new schools were built in 1874.

Sources cited:

1) National Archive: ED 49/9043

2) Gillard D (2018) Education in England

3) National Archive: ED 49/9043

4) National Archive: ED 49/9043

5) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

6) Gillard D (2018) Education in England

7) National Archive: ED 49/9043

8) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

9) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

10) National Archive: ED 21/20112

11) Hannam JB (1984) The Employment of Working-Class Women in Leeds, 1880-1914 (PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield)

12) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

13) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

14) The Scotsman, 1906.

1) National Archive: ED 49/9043

2) Gillard D (2018) Education in England

3) National Archive: ED 49/9043

4) National Archive: ED 49/9043

5) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

6) Gillard D (2018) Education in England

7) National Archive: ED 49/9043

8) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

9) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

10) National Archive: ED 21/20112

11) Hannam JB (1984) The Employment of Working-Class Women in Leeds, 1880-1914 (PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield)

12) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

13) West Yorkshire Archive: WDP26/7/3-26

14) The Scotsman, 1906.