|

⬆︎ Use pull down menus above to navigate the site.

|

|

Concerning “The Recent Daring Burglary at Gildersome Parsonage"

By Andrew Bedford © 2018

By Andrew Bedford © 2018

|

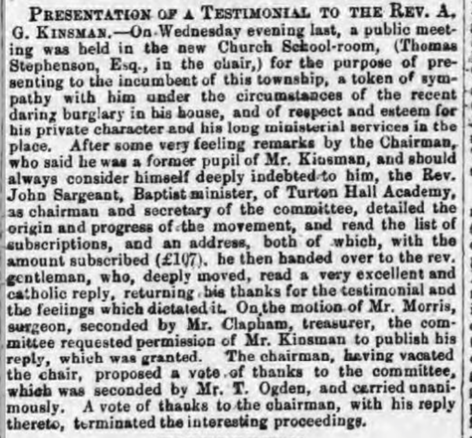

In 1878 an article in a local newspaper reported the retirement of Superintendent John Pollard from the Skyrack Division of the West Yorkshire Constabulary. The article listed Mr Pollard’s more notable achievements, including a burglary at Gildersome in which six men had broken into the parsonage. The report goes on to relate that, in gratitude for services rendered, the ‘Reverend AG Kinsman presented Mr Pollard with a silver snuff box, which the recipient cherishes to this day.’ ¹ The following discussion examines the circumstances that led to the Reverend Kinsman’s generous expression of gratitude following a criminal encounter that would receive newspaper coverage on a national scale² and outlines the events that resulted in several local men facing the death penalty. Those events are scrutinised alongside a similar event that had taken place almost exactly a year earlier and within the context of widespread anxieties concerning contemporary perceptions of crime and criminality.

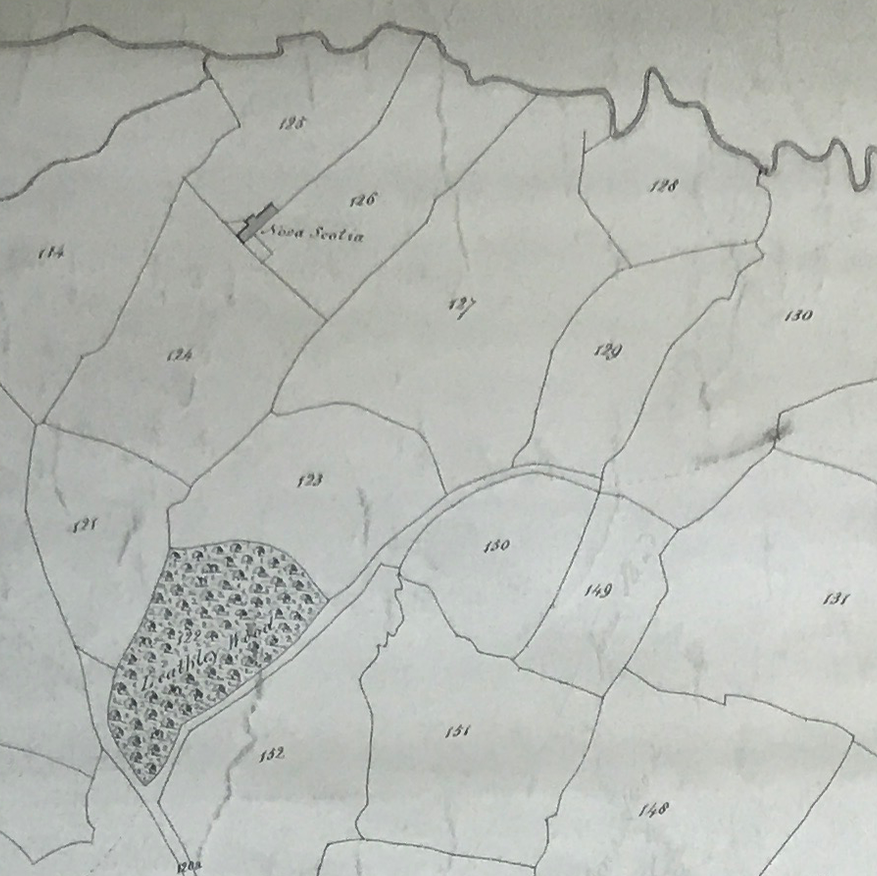

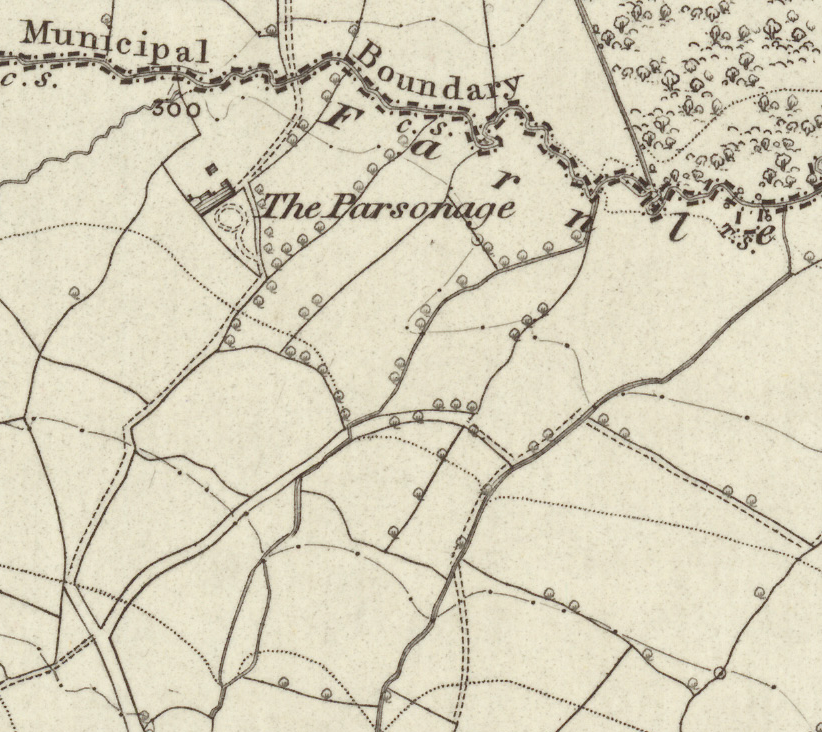

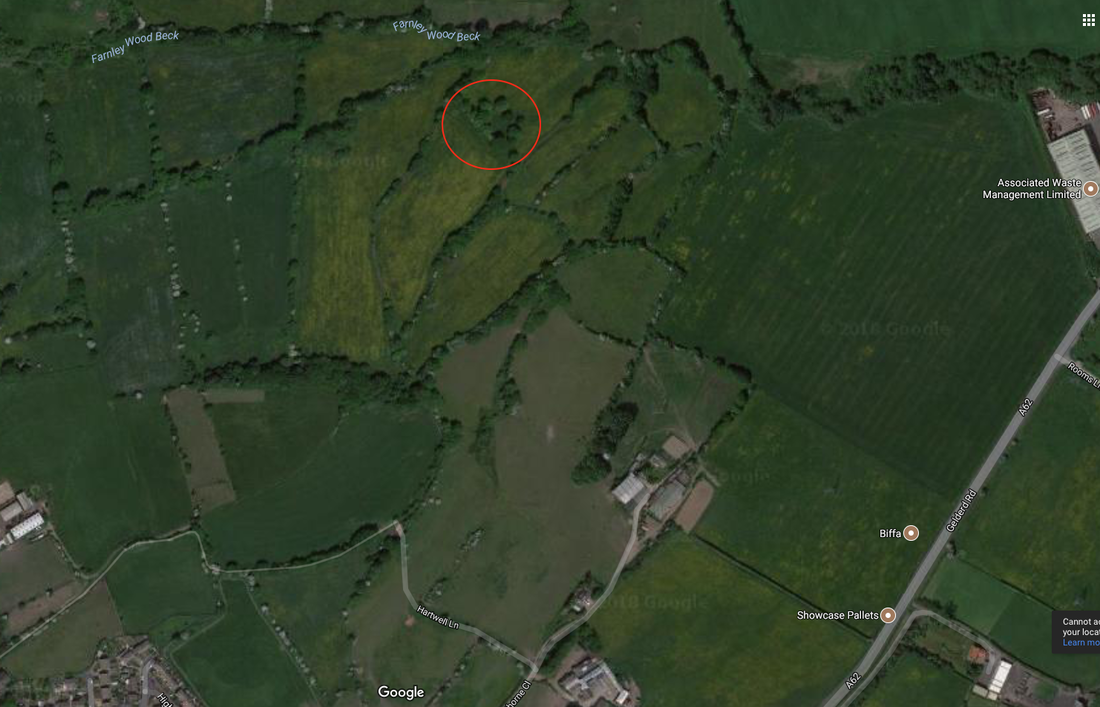

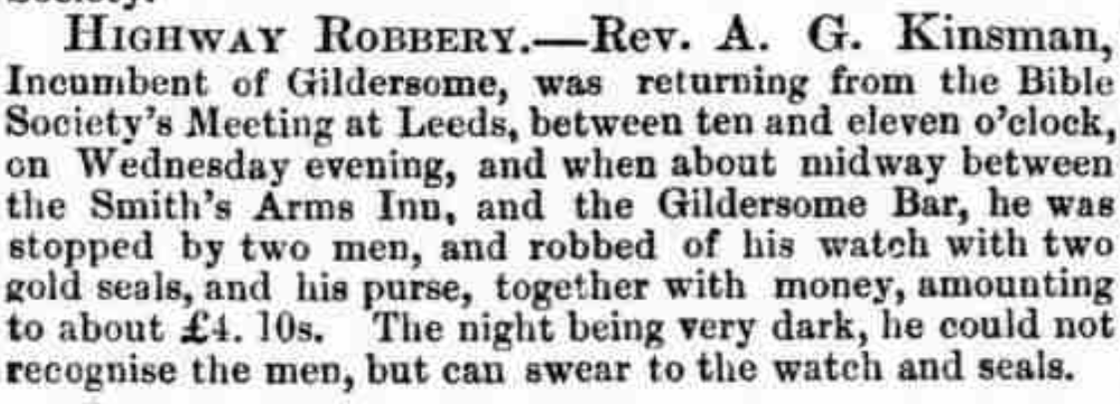

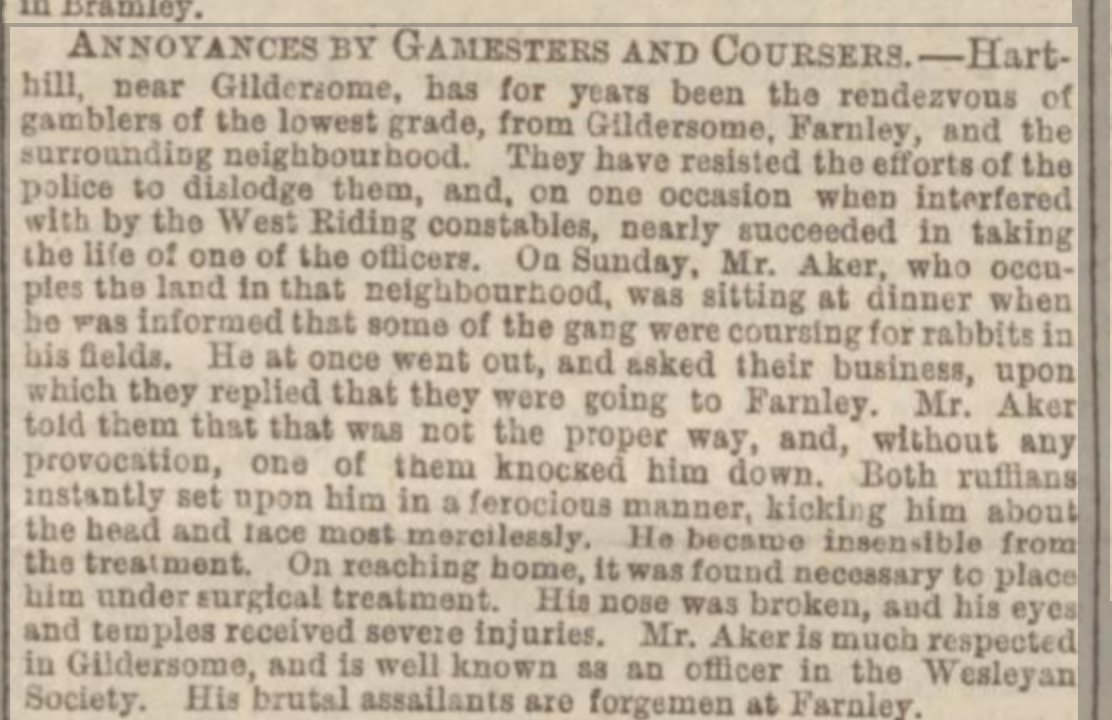

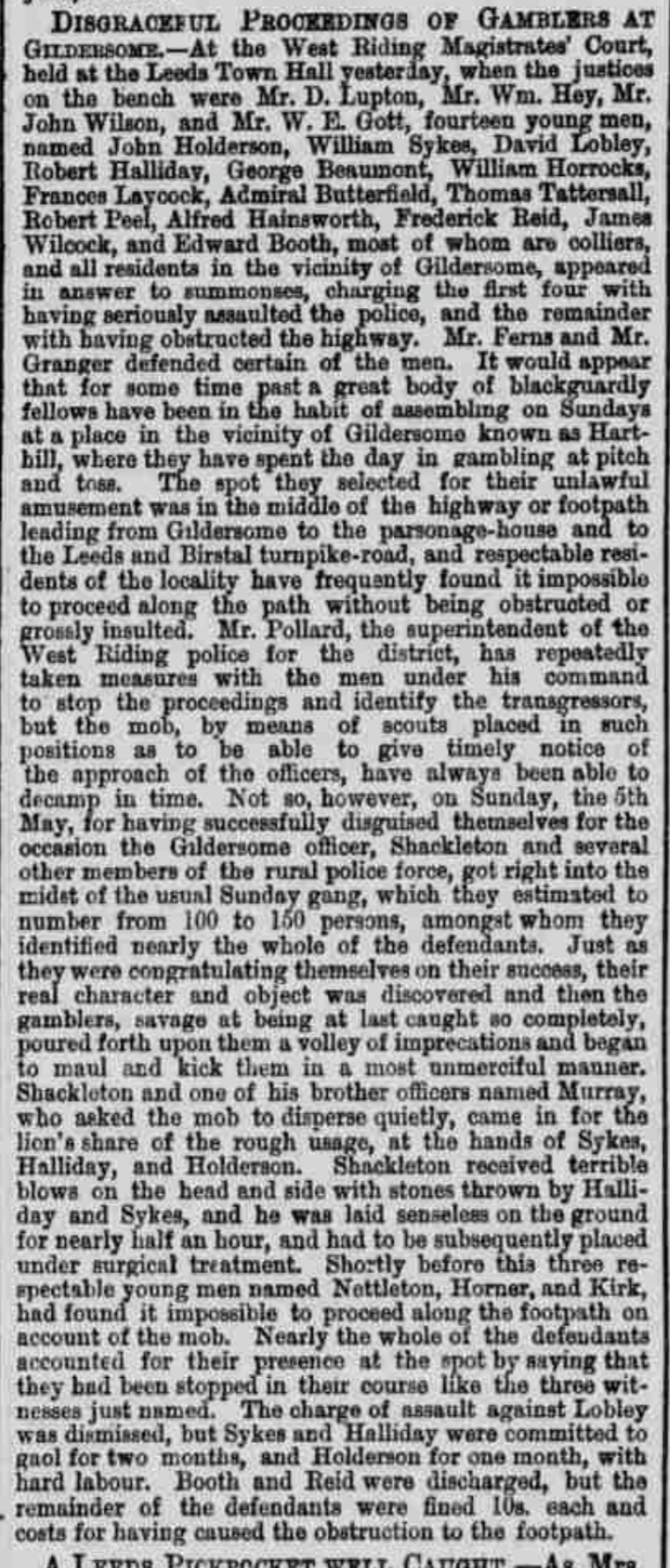

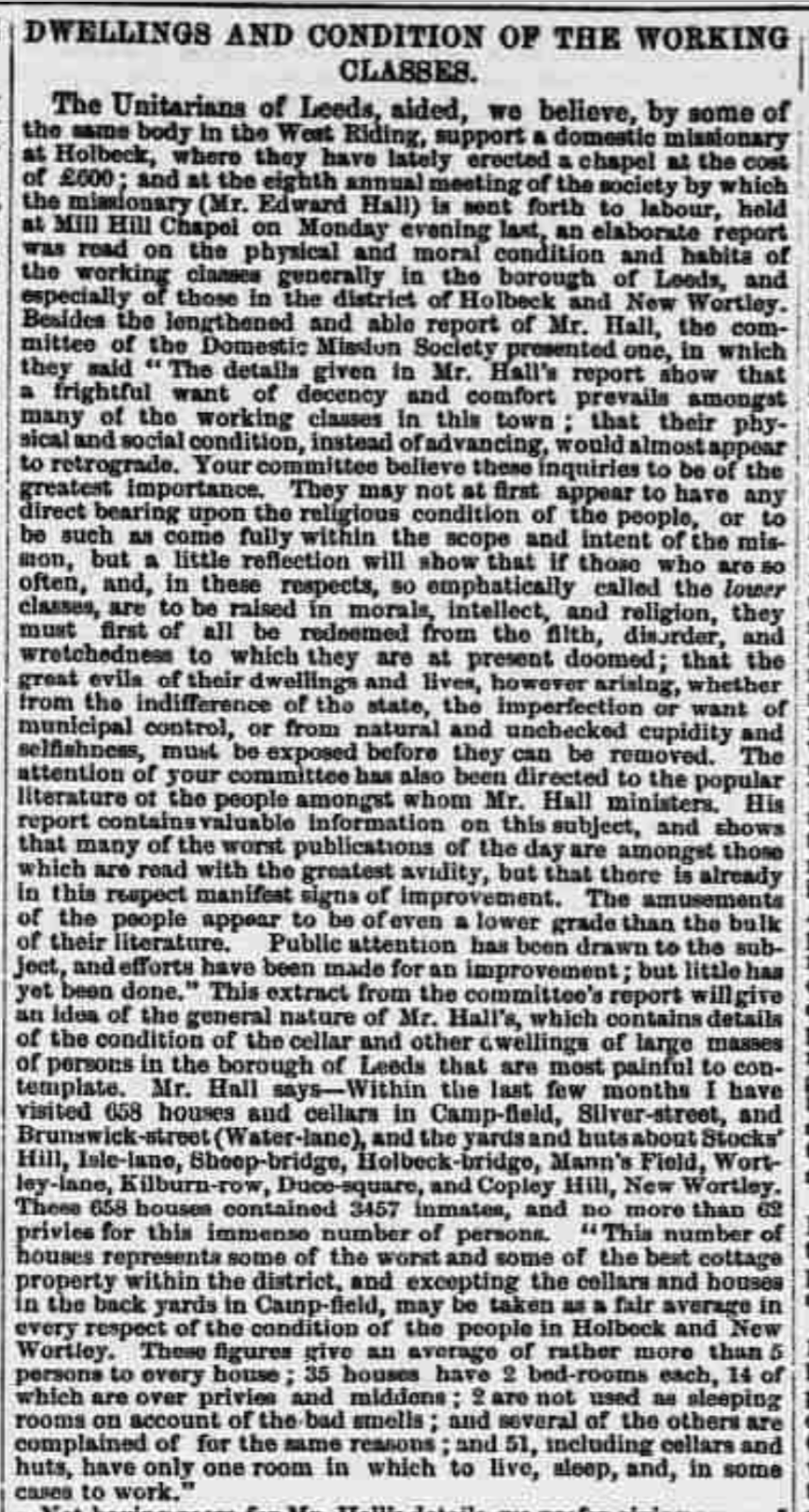

The Reverend Andrew Guyse Kinsman and his family lived at an isolated parsonage at a location known locally as Nova Scotia. The etymology of that name reveals that it was often ascribed to remote and difficult to access locations.³ The parsonage was purchased in 1793 by the Diocese of Wakefield for the Benefice of Gildersome and consisted of five acres on two plots called, at that time, the Low Carrs which contained a two storey dwelling house and all the appurtenances of a working farm.⁴ Gildersome's curate had been living there since 1819. Situated as it was, on the boundary with Farnley, it's location was obviously secluded and would have presented an attractive target for desperate men with felonious intentions. The three maps on the right show how little the northern region of Gildersome has changed in the past 218 years. The red circle in the bottom aerial photo marks the location of The Parsonage/ Nova Scotia. (click on each map to view an enlarged version) The opening of the new turnpike road (Gelderd Road) in 1825 had provided Gildersome with easier access to the neighbouring city of Leeds. This would have endowed a considerable improvement to Gildersome’s commercial interests, though this was an improvement that came at a cost. Gelderd Road also provided those of an unsavoury nature with a convenient route to the remote locations along Gildersome’s northern boundary. The scattered estates and outlying farms that had previously enjoyed a relatively peaceful existence were now beset by “blackguardly fellows” intent on taking nefarious advantage of the area’s seclusion. For illustration of this point, click on the newspaper accounts to the right.* On the morning of the 13th of February 1858, between 1 and 2 am, the Reverend Andrew Guyse Kinsman, incumbent of Gildersome since 1819 and ‘a gentleman considerably advanced in years’ ⁵ was woken by the sound of screaming emanating from the bedroom occupied by his two young nieces. Contemporary newspaper reports relate how five or six men, some wearing masks and others with their faces blackened, had entered the house after opening a kitchen window and releasing the bolt on the back door. When Kinsman approached the bedroom occupied by his nieces, a man with a pistol in one hand and a lantern in the other ordered him to return to his bed or have his brains blown out.⁶ As this was happening, the occupants of a third bedroom, the curate’s son, John Guyse Kinsman and his wife, Rebecca Catherine, were also alerted. We are told that the younger Kinsman leapt out of bed with the intention of arming himself with a loaded pistol he kept in a chest of drawers. As he endeavoured to do so, three armed men burst into the room presenting pistols at his head, stating that they knew there was money in the house and if it were not given up his life would be taken. His pistol was retrieved from the drawer and handed to a fourth intruder who cocked it and pointed it at Kinsman’s head. At which point, Mrs Kinsman intervened on her husband’s behalf, pleading that his life should be spared and assuring the assailants that any money in the house would be handed over. £25 in five pound notes drawn from Beckett’s Bank, Leeds was duly given up to the intruders.⁷ Apparently unimpressed, one of the “ruffians” then uttered the following threat: ‘if you don’t hand out some bullion, we’ll murder all in the house.’ ⁸ By the time the intruders departed, the family had been relieved of £25 in banknotes, £3 and10 shillings in gold, between £1 and £2 in silver, a watch and seals, a gold ring, and a single barrelled pistol. On making his departure, one of the intruders bade the family goodnight, adding that ‘your money has saved your lives, but we are not going yet, and if any of you stir, or strike a light, we will come back and murder you.’ ⁹ To read a detailed account of the burglary by a contemporary newspaper click here. The forces of law and order were quick to respond. Within a week of the robbery, acting upon information provided by the Kinsman family, Mr John Pollard, Superintendent of the Skyrack Division of the West Riding Constabulary, made an arrest. John Hainsworth (35) was apprehended at his mother’s house in Holbeck on Saturday the 20th of February. ‘The charge was stated to him, and he said that on the night mentioned he went home at six o’clock in the evening and was not out of the house again till late next morning.’ ¹⁰ As Pollard was detaining his man, police officer James Midgley was arresting Josiah Williamson (27), also of Holbeck, charging him with involvement in the burglary. Williamson was cautioned and made a statement admitting that he had recently visited Gildersome with a man named Webster, though he insisted he had no connection to the robbery. Williamson also had in his possession a small package containing blue powder, which he said was for treating a sore on his leg.¹¹ Superintendent Pollard duly escorted Hainsworth and Williamson to the parsonage at Gildersome where they were identified by some of the occupants as having taken part in the robbery. It seems, however, that the Rev. Kinsman was unable to make a positive identification. When the case was brought before the West Riding Magistrates’ Court in early March, Mr John Guyse Kinsman identified the prisoner Hainsworth as being the man who had appropriated his loaded pistol and threatened him with it. Kinsman related how Hainsworth had a sort of covering over a portion of his face. It appeared to be made of cloth, and there were holes in it for the eyes, the nose, and the mouth. The cloth partially projected from the face, and looking edgeways the face could be seen. That man was the prisoner Hainsworth. He was brought to the parsonage by Superintendent Pollard and a police officer on the Saturday after the robbery. I then recognised him immediately, and his voice confirmed the identity. I heard him speak several times at the time of the burglary.¹² |

Hainwsorth grew up in the hovels and shacks of Stocks Hill, Holbeck, mentioned in the article above.

|

Kinsman then turned his attention to the second defendant.

The prisoner Williamson is also one of the men who came into my bedroom. His face was blackened and streaked with pale blue. I recognised him when he was brought to the parsonage by the police. His voice was a husky one, and a very peculiar one.¹³

The witness also related how he had seen footprints the morning after the burglary, which appeared to have been left by iron-plated clogs. One of Williamson’s clogs had been examined, but no comparison could be proved.

Mrs Rebecca Catherine Kinsman also identified Hainsworth as being the man in the mask. Like her husband, she had caught sight of the defendant’s face from the side. ‘She also saw him partially raise his mask while he was in the room, and had a good opportunity of seeing.’ In addition, Mrs Kinsman identified Williamson as the man with his face blackened and streaked. ‘His voice was husky and peculiar. She believed that he [had worn] a low-crowned or “billycock” hat.’ ¹⁴

Miss Emma Eliza Hook (at 18 the elder of Rev. Kinsman’s two nieces) described how the burglars had burst into the bedroom she shared with her younger sister, Julia Louisa Hook. Miss Hook also made reference to the ‘peculiar mask’ worn by one of the intruders and identified that man as Hainsworth. She ‘stated that he was armed with a life-preserver¹⁵ with which he struck at her and her sister while they were covered over with the bed-clothes.’ Miss Hook also stated that she heard Hainsworth call out to one of the men, “bring me a light, Jos.” ¹⁶

Having considered the evidence set before them, the magistrates were moved to remark that

they were exceedingly sorry that a clergyman in Mr Kinsman’s advanced period of life should have been subject to so great an outrage; and at the same time they must express their astonishment and admiration at the calm way in which he had acted, and at the extreme prudence which had been manifested by all the members of his family. ¹⁷

Needless to say, Hainsworth and Williamson were extended no such sympathies. They were sent for trial at the York Assizes where a verdict of death would be recorded against them.

In May 1858, a further three men were brought before the West Riding Magistrates under charges of being concerned in the ‘late daring burglary at Gildersome parsonage.’ Jesse Kay, James Duthoit and Reuben Smith, alias Glover, were taken to Gildersome parsonage where ‘Kay and Duthroyd [sic] were identified as two of the men who committed the burglary.’ Smith, alias Glover, could not be positively identified and accordingly discharged.¹⁸ ¹⁹

The prisoner Williamson is also one of the men who came into my bedroom. His face was blackened and streaked with pale blue. I recognised him when he was brought to the parsonage by the police. His voice was a husky one, and a very peculiar one.¹³

The witness also related how he had seen footprints the morning after the burglary, which appeared to have been left by iron-plated clogs. One of Williamson’s clogs had been examined, but no comparison could be proved.

Mrs Rebecca Catherine Kinsman also identified Hainsworth as being the man in the mask. Like her husband, she had caught sight of the defendant’s face from the side. ‘She also saw him partially raise his mask while he was in the room, and had a good opportunity of seeing.’ In addition, Mrs Kinsman identified Williamson as the man with his face blackened and streaked. ‘His voice was husky and peculiar. She believed that he [had worn] a low-crowned or “billycock” hat.’ ¹⁴

Miss Emma Eliza Hook (at 18 the elder of Rev. Kinsman’s two nieces) described how the burglars had burst into the bedroom she shared with her younger sister, Julia Louisa Hook. Miss Hook also made reference to the ‘peculiar mask’ worn by one of the intruders and identified that man as Hainsworth. She ‘stated that he was armed with a life-preserver¹⁵ with which he struck at her and her sister while they were covered over with the bed-clothes.’ Miss Hook also stated that she heard Hainsworth call out to one of the men, “bring me a light, Jos.” ¹⁶

Having considered the evidence set before them, the magistrates were moved to remark that

they were exceedingly sorry that a clergyman in Mr Kinsman’s advanced period of life should have been subject to so great an outrage; and at the same time they must express their astonishment and admiration at the calm way in which he had acted, and at the extreme prudence which had been manifested by all the members of his family. ¹⁷

Needless to say, Hainsworth and Williamson were extended no such sympathies. They were sent for trial at the York Assizes where a verdict of death would be recorded against them.

In May 1858, a further three men were brought before the West Riding Magistrates under charges of being concerned in the ‘late daring burglary at Gildersome parsonage.’ Jesse Kay, James Duthoit and Reuben Smith, alias Glover, were taken to Gildersome parsonage where ‘Kay and Duthroyd [sic] were identified as two of the men who committed the burglary.’ Smith, alias Glover, could not be positively identified and accordingly discharged.¹⁸ ¹⁹

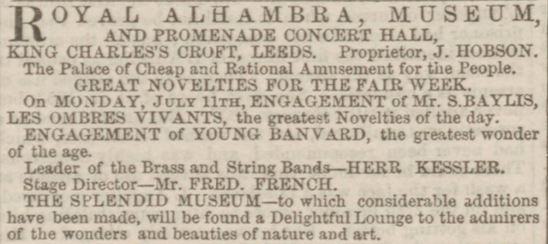

What's on at the Alhambra: Leeds Times 11 Jul 1857

What's on at the Alhambra: Leeds Times 11 Jul 1857

The charges against Kay were also eventually dropped through lack of evidence.²⁰ However, on July 19, 1858, James Duthoit was tried at the York Assizes for having committed burglary at the house of Andrew Guyse Kinsman of Gildersome. Duthoit had protested his innocence at the time of his arrest. Furthermore, his claim was corroborated by his daughter who, along with a workmate, swore that on the night of the robbery Duthoit had been at home in bed. It was claimed that the young women had spent the evening at the Alhambra in Leeds,²¹ returning home at eleven at which time the prisoner had let them in to the house. When they rose for work at five the following morning, Duthoit was still in his bed at Holbeck. If this information was correct then, given the distances involved, it was estimated that Duthoit could not have been at the parsonage. In order to substantiate their story, the girls also produced a handbill from the performance at the Alhambra. However, it appears that Superintendent Pollard, having been instructed to investigate, was able to establish that the bill provided had been procured after the event had taken place. Thus undermining the witness’ credibility and what had promised to be an unassailable alibi. With his alibi thus compromised, positive identification provided by Mrs Rebecca Kinsman ensured that Duthoit was found guilty and a verdict of death was duly recorded.²²

It may be useful, at this point, to take some account of the context in which the Gildersome burglary had taken place. The Crimean War had ended in February 1856, generating widespread anxieties of recently discharged and unemployed soldiers roaming the countryside in search of sustenance.²³ Added to which, the 1853 Penal Servitude Act had created another harbinger of impending doom: the so-called “ticket of leave man” newly returned from his sentence of penal servitude in the colonies.²⁴ It has been suggested that these elements, together with a continuing increase in popular newspaper sales, had given rise to a generalised panic at the idea of bands of ex soldiers and convicts visiting terror on an unprotected countryside - a situation that had been instrumental in the passing of the County and Borough Police Act of 1856.²⁵ The West Riding Constabulary, under whose authority Superintendent Pollard investigated the Gildersome robbery, had been inaugurated in response to the act.

The anxieties alluded to above had already been realised, to some extent, in March 1857. In a case of striking similarity to that of the Gildersome burglary, Mr William Bradley of Manor Oaks, Sheffield had been robbed of £30 in coins and banknotes, three silver teapots, two silver sugar basins, thirty-six silver teaspoons, twelve silver forks, one silver-plated sugar basin, two gold watches, and other property.²⁶

At around 2 am five men had entered Mr Bradley’s bedroom demanding money. The court heard how the men ‘wore black masks, hanging down from their caps, with large eye holes, and not tightly fitted to the face.’ It was stated that ‘one of the burglars carried a life preserver [and] another had a revolver.’ ²⁷ The revolver, it would later transpire, had been found in one of the ground floor rooms and belonged to Bradley. In the ensuing struggle, Bradley was attacked and suffered a broken finger in attempting to ward off the blows from the life preserver. It was also stated that Mrs Bradley was struck on the bosom, causing her considerable pain. While it is evident that Mr and Mrs Bradley had been attacked and had suffered injury, it may be notable that the Gildersome incumbent and his family had been able to survive their ordeal largely unscathed.²⁸

It is evident from the number of men involved at Manor Oaks and the fact of their being masked and armed that there are clear similarities with the events described at Gildersome parsonage. In both cases, for example, a gun had been found on the premises and turned against its owner. In the Gildersome robbery, however, the intruders had been described as being armed with pistols when they entered the premises. A point that was never contested by the defence, though it should be borne in mind that to have done so would have amounted to an admission of the accused’s involvement. It is not inconceivable that a certain amount of exaggeration might have taken place, either on the part of the prosecution in order to secure as stiff a sentence as possible, or indeed of inaccurate, sensation-seeking journalism.

Following the robbery at Manor Oaks, inspector Linley of Sheffield police had examined the garden in front of the house and, as appears to have been the case at Gildersome, footprints were found that might provide evidence against the perpetrators. At Manor Oaks, however, it would be established that boots worn by one of the accused corresponded to the marks found in the flowerbed and this was used as evidence against him.

A significant disparity between the two cases is that at the Manor Oaks trial a number of people had been traced who were able to confirm that they had witnessed the defendants spending sovereigns and attempting to change banknotes in the days following the robbery.²⁹ In the Gildersome robbery, as Mr Seymour, appearing for the defence had stated: ‘none of the property had been recovered. The watch had not been found at any pawnbroker’s, nor had any of the £5 notes been traced.’ ³⁰

Another critical difference to the Gildersome case was that witnesses were brought forward to confirm that seven men had been identified loitering in the area. Dickinson, Gledall,³¹ Simpson, Glover, Ewings, Gouldthorpe, and Marsden, most of who were Barnsley residents had been seen and recognised by witnesses.³² As was the case at Gildersome, some of those were discharged and only three of the accused (Gledall, Dickinson and Marsden) would be found guilty. However, perhaps the most noteworthy connection between the two cases is provided by the fourth name on the original list of loiterers. After his acquittal, Reuben Glover, alias Smith, moved from Barnsley to an address in Leeds, where, as we have seen above, he was apprehended (and later discharged) for his alleged involvement in the Gildersome parsonage robbery.

It may be justifiably argued that the credibility of the Sheffield prosecution witnesses is open to doubt given that a substantial reward for information had been posted.³³ Nevertheless, in comparing the two cases it is difficult to reach a conclusion other than that the Manor Oaks offenders had been convicted on a far stronger body of evidence than that presented in the Gildersome case, in which an absence of such witnesses meant that the men found guilty of the Gildersome burglary were convicted entirely on evidence provided by their alleged victims.

Passing sentence on the Manor Oaks offenders, Mr Baron Martin made the following statement:

Daniel Dickinson, William Gledall, and Henry Marsden, you have been found guilty of one of the most barbarous burglaries I have ever heard before me … It is my duty to cause the sentence of death to be recorded against you … your lives will be spared, but it is my duty to pass upon you the most severe punishment the law allows, which is that you will have to pass the remainder of your lives as slaves … transported beyond the seas for the term of your natural lives.³⁴

In their turn the Gildersome Parsonage defendants (Josiah Williamson, John Hainsworth and James Duthoit) would be dealt with in similar fashion. Mr Justice Byles, passing sentence on Williamson and Hainsworth was moved to state that ‘if the law were not strong enough to deal with the likes of such persons as you, then the maxim that every man’s house is his castle would become an idle boast.’ ³⁵ The law would prove not only strong enough, but also intransigent in its obligations. Following the conviction, a petition to the Home Secretary made by the Rev. Ward of Little Holbeck, Leeds, received the following response:

Dear Sir. Sir George Grey having considered the papers which you forwarded to him on behalf of Josiah Williamson, John Hainsworth and James Duthoit, I am instructed to acquaint you that he regrets that he can see [no sufficient?] reason for doubting the correctness of the verdict, or for advising any interference on the part of the Crown with the convicts’ sentence.³⁶

The Home Secretary’s intransigence was perhaps reflective of an era in which offences of this nature had been viewed with increasing trepidation. From the comfortable distance of a present day perspective the sentences passed on Williamson, Hainsworth and Duthoit can appear to have been arrived at in a spirit more inclined toward expediency than impartiality. However, it should be borne in mind that, within the context of the 1850s, those convicted of the Gildersome parsonage robbery were dealt with in accordance with the legal system of the day. The circumstances of the case clearly indicate that a serious misdemeanour had taken place, though we need to be mindful that this was established entirely on the grounds of evidence provided by the victims.³⁷ The Gildersome parsonage burglary was without doubt a terrifying experience, though it is not beyond the scope of possibility that the Kinsman family were not the only victims.

It may be useful, at this point, to take some account of the context in which the Gildersome burglary had taken place. The Crimean War had ended in February 1856, generating widespread anxieties of recently discharged and unemployed soldiers roaming the countryside in search of sustenance.²³ Added to which, the 1853 Penal Servitude Act had created another harbinger of impending doom: the so-called “ticket of leave man” newly returned from his sentence of penal servitude in the colonies.²⁴ It has been suggested that these elements, together with a continuing increase in popular newspaper sales, had given rise to a generalised panic at the idea of bands of ex soldiers and convicts visiting terror on an unprotected countryside - a situation that had been instrumental in the passing of the County and Borough Police Act of 1856.²⁵ The West Riding Constabulary, under whose authority Superintendent Pollard investigated the Gildersome robbery, had been inaugurated in response to the act.

The anxieties alluded to above had already been realised, to some extent, in March 1857. In a case of striking similarity to that of the Gildersome burglary, Mr William Bradley of Manor Oaks, Sheffield had been robbed of £30 in coins and banknotes, three silver teapots, two silver sugar basins, thirty-six silver teaspoons, twelve silver forks, one silver-plated sugar basin, two gold watches, and other property.²⁶

At around 2 am five men had entered Mr Bradley’s bedroom demanding money. The court heard how the men ‘wore black masks, hanging down from their caps, with large eye holes, and not tightly fitted to the face.’ It was stated that ‘one of the burglars carried a life preserver [and] another had a revolver.’ ²⁷ The revolver, it would later transpire, had been found in one of the ground floor rooms and belonged to Bradley. In the ensuing struggle, Bradley was attacked and suffered a broken finger in attempting to ward off the blows from the life preserver. It was also stated that Mrs Bradley was struck on the bosom, causing her considerable pain. While it is evident that Mr and Mrs Bradley had been attacked and had suffered injury, it may be notable that the Gildersome incumbent and his family had been able to survive their ordeal largely unscathed.²⁸

It is evident from the number of men involved at Manor Oaks and the fact of their being masked and armed that there are clear similarities with the events described at Gildersome parsonage. In both cases, for example, a gun had been found on the premises and turned against its owner. In the Gildersome robbery, however, the intruders had been described as being armed with pistols when they entered the premises. A point that was never contested by the defence, though it should be borne in mind that to have done so would have amounted to an admission of the accused’s involvement. It is not inconceivable that a certain amount of exaggeration might have taken place, either on the part of the prosecution in order to secure as stiff a sentence as possible, or indeed of inaccurate, sensation-seeking journalism.

Following the robbery at Manor Oaks, inspector Linley of Sheffield police had examined the garden in front of the house and, as appears to have been the case at Gildersome, footprints were found that might provide evidence against the perpetrators. At Manor Oaks, however, it would be established that boots worn by one of the accused corresponded to the marks found in the flowerbed and this was used as evidence against him.

A significant disparity between the two cases is that at the Manor Oaks trial a number of people had been traced who were able to confirm that they had witnessed the defendants spending sovereigns and attempting to change banknotes in the days following the robbery.²⁹ In the Gildersome robbery, as Mr Seymour, appearing for the defence had stated: ‘none of the property had been recovered. The watch had not been found at any pawnbroker’s, nor had any of the £5 notes been traced.’ ³⁰

Another critical difference to the Gildersome case was that witnesses were brought forward to confirm that seven men had been identified loitering in the area. Dickinson, Gledall,³¹ Simpson, Glover, Ewings, Gouldthorpe, and Marsden, most of who were Barnsley residents had been seen and recognised by witnesses.³² As was the case at Gildersome, some of those were discharged and only three of the accused (Gledall, Dickinson and Marsden) would be found guilty. However, perhaps the most noteworthy connection between the two cases is provided by the fourth name on the original list of loiterers. After his acquittal, Reuben Glover, alias Smith, moved from Barnsley to an address in Leeds, where, as we have seen above, he was apprehended (and later discharged) for his alleged involvement in the Gildersome parsonage robbery.

It may be justifiably argued that the credibility of the Sheffield prosecution witnesses is open to doubt given that a substantial reward for information had been posted.³³ Nevertheless, in comparing the two cases it is difficult to reach a conclusion other than that the Manor Oaks offenders had been convicted on a far stronger body of evidence than that presented in the Gildersome case, in which an absence of such witnesses meant that the men found guilty of the Gildersome burglary were convicted entirely on evidence provided by their alleged victims.

Passing sentence on the Manor Oaks offenders, Mr Baron Martin made the following statement:

Daniel Dickinson, William Gledall, and Henry Marsden, you have been found guilty of one of the most barbarous burglaries I have ever heard before me … It is my duty to cause the sentence of death to be recorded against you … your lives will be spared, but it is my duty to pass upon you the most severe punishment the law allows, which is that you will have to pass the remainder of your lives as slaves … transported beyond the seas for the term of your natural lives.³⁴

In their turn the Gildersome Parsonage defendants (Josiah Williamson, John Hainsworth and James Duthoit) would be dealt with in similar fashion. Mr Justice Byles, passing sentence on Williamson and Hainsworth was moved to state that ‘if the law were not strong enough to deal with the likes of such persons as you, then the maxim that every man’s house is his castle would become an idle boast.’ ³⁵ The law would prove not only strong enough, but also intransigent in its obligations. Following the conviction, a petition to the Home Secretary made by the Rev. Ward of Little Holbeck, Leeds, received the following response:

Dear Sir. Sir George Grey having considered the papers which you forwarded to him on behalf of Josiah Williamson, John Hainsworth and James Duthoit, I am instructed to acquaint you that he regrets that he can see [no sufficient?] reason for doubting the correctness of the verdict, or for advising any interference on the part of the Crown with the convicts’ sentence.³⁶

The Home Secretary’s intransigence was perhaps reflective of an era in which offences of this nature had been viewed with increasing trepidation. From the comfortable distance of a present day perspective the sentences passed on Williamson, Hainsworth and Duthoit can appear to have been arrived at in a spirit more inclined toward expediency than impartiality. However, it should be borne in mind that, within the context of the 1850s, those convicted of the Gildersome parsonage robbery were dealt with in accordance with the legal system of the day. The circumstances of the case clearly indicate that a serious misdemeanour had taken place, though we need to be mindful that this was established entirely on the grounds of evidence provided by the victims.³⁷ The Gildersome parsonage burglary was without doubt a terrifying experience, though it is not beyond the scope of possibility that the Kinsman family were not the only victims.

Leeds Intelligencer 27/3/1858

Leeds Intelligencer 27/3/1858

Epilogue:

Josiah Williamson was transported to Her Majesty’s Convict Prison, Gibraltar. He was later transferred to Millbank Prison from where he was released on licence in April 1873.³⁸ As a ‘ticket of leave man’ Williamson returned to Holbeck where he married Sarah Howarth in 1873.³⁹ He died in 1897 aged 66.⁴⁰

John Hainsworth was transported to Australia in 1860 on the ship, Palmerston. He was granted a conditional pardon in 1871.⁴¹

James Duthoit was transported to Australia in 1862 on the ship, Merchantman. In yet another connection to the Manor Oaks robbery, Gleadall and Marsden were listed on the same vessel.⁴² Duthoit received a conditional pardon in1871.⁴³ He died in Green, Western Australia, 1875.⁴⁴

Some 3 years after the robbery, the Kinsman family were residing at Yarra House in Gildersome. At the age of 73, Andrew Guyse Kinsman was continuing his duties as the curate of Gildersome.⁴⁵ He died in 1867 at the age of 79 leaving an estate to the value of £600.⁴⁶ In the 1861, census Kinsman's daughter, Louisa, is found living at 'Knovy' (the Parsonage) with her husband, Robert Webster, and their family.

John Guyse Kinsman and his wife Rebecca Catherine Kinsman were also resident at Yarra House in 1861.⁴⁷ In 1891, John Guyse Kinsman was retired and living on his own means, the resident of 3 St George’s Terrace, Plymouth.⁴⁸ He died in 1900 at the age of 80.⁴⁹ Rebecca C Kinsman succeeded him by 20 years, dying at the age of 93.⁵⁰

In 1861 Emma Eliza Hook and Julia Louisa Hook were still residing with the Kinsmans at Yarra House in Gildersome. In 1862 Emma Eliza Hook married Samuel Troughton Ambler. They were residing at Back Lane, Drighlington in 1901.⁵¹ Her younger sister has proved more difficult to trace. However, in 1866 a Julia Louisa Hook (born in England and the same age) was married to George Wm. McCormick in Ohio, USA.⁵² ⁵³

In 1878 Superintendent John Pollard of the West Riding Constabulary retired from his post. Mr Pollard’s career was declared to have been ‘an excellent example of what may be done by sterling integrity and assiduous attention to duty.’ ⁵⁴ He retired on a pension of £125 per annum.

Josiah Williamson was transported to Her Majesty’s Convict Prison, Gibraltar. He was later transferred to Millbank Prison from where he was released on licence in April 1873.³⁸ As a ‘ticket of leave man’ Williamson returned to Holbeck where he married Sarah Howarth in 1873.³⁹ He died in 1897 aged 66.⁴⁰

John Hainsworth was transported to Australia in 1860 on the ship, Palmerston. He was granted a conditional pardon in 1871.⁴¹

James Duthoit was transported to Australia in 1862 on the ship, Merchantman. In yet another connection to the Manor Oaks robbery, Gleadall and Marsden were listed on the same vessel.⁴² Duthoit received a conditional pardon in1871.⁴³ He died in Green, Western Australia, 1875.⁴⁴

Some 3 years after the robbery, the Kinsman family were residing at Yarra House in Gildersome. At the age of 73, Andrew Guyse Kinsman was continuing his duties as the curate of Gildersome.⁴⁵ He died in 1867 at the age of 79 leaving an estate to the value of £600.⁴⁶ In the 1861, census Kinsman's daughter, Louisa, is found living at 'Knovy' (the Parsonage) with her husband, Robert Webster, and their family.

John Guyse Kinsman and his wife Rebecca Catherine Kinsman were also resident at Yarra House in 1861.⁴⁷ In 1891, John Guyse Kinsman was retired and living on his own means, the resident of 3 St George’s Terrace, Plymouth.⁴⁸ He died in 1900 at the age of 80.⁴⁹ Rebecca C Kinsman succeeded him by 20 years, dying at the age of 93.⁵⁰

In 1861 Emma Eliza Hook and Julia Louisa Hook were still residing with the Kinsmans at Yarra House in Gildersome. In 1862 Emma Eliza Hook married Samuel Troughton Ambler. They were residing at Back Lane, Drighlington in 1901.⁵¹ Her younger sister has proved more difficult to trace. However, in 1866 a Julia Louisa Hook (born in England and the same age) was married to George Wm. McCormick in Ohio, USA.⁵² ⁵³

In 1878 Superintendent John Pollard of the West Riding Constabulary retired from his post. Mr Pollard’s career was declared to have been ‘an excellent example of what may be done by sterling integrity and assiduous attention to duty.’ ⁵⁴ He retired on a pension of £125 per annum.

Sources and notes:

* All newspaper images are from:

British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

1] Yorkshire Post and Intelligencer, Tuesday, April 9, 1878.

2] The burglary received coverage across the country in newspapers ranging from the Hampshire Advertiser to the Dundee, Perth, Forfar, and Fife People’s Journal.

3] Field, J. (1972) English Field Names: a Dictionary. David and Charles, Newton Abbot, P.153.

4] West Yorkshire Archive Service WDP26/3/21. Extract from deed of bargain and sale 13 Mar 1793.

5] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

6] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

7] In 1858 banknotes would be very difficult to convert into cash, particularly so for those at the lower end of society who would probably have to “fence” them at a considerable discount.

8] Morning Advertiser, Friday, March 5, 1858.

9] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

10] Leeds Intelligencer, March 6, 1858.

11] Leeds Intelligencer, March 6, 1858.

12] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

13] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

14] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

15] The life preserver consisted of a sturdy length of cane about 12 inches long. At one end was a knob consisting of 5 or 6 ounces of lead, at the other, a loop of leather strapping to secure it to the user’s wrist. Somewhat ironically, the life preserver became a popular self-defense device in the wake of the Garotte robberies that were prevalent in 1850s England.

16] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

17] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

18] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, May 8, 1858

19] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, May 5, 1858.

20] Leeds Times, May 15, 1858.

21] The Royal Alhambra Museum and Promenade Concert Hall “the palace of cheap and rational amusement for the people” was situated in King Charles’s Croft, Leeds.

22] Leeds Times, May 24, 1858.

23] Taylor, D. (1998) Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914. Macmillan Press, Basingstoke, P.78.

24] The Leeds Times, December 6, 1858, reported that Mr. Wilson Overend, chairman of the West Riding Quarter Sessions, ‘referred to the great increase of crime in the district, and to the ill effects attendant upon the release of convicts upon tickets-of-leave.’

25] Taylor, D. (1998) Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914. Macmillan Press, Basingstoke. P.78.

26] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

27] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

28] The Hook sisters claimed to have been struck by life preservers during the robbery, though no injuries appear to have been reported at the trial.

29] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

30] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

31] The Sheffield Daily Telegraph uses the spelling ”Gledall” though prison documents use Gleadall.

32] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

33] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

34] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

35] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

36] Prison Register Correspondence and Warrants.

37] It should also be borne in mind that the entire narrative of the burglary is based upon evidence provided by the victims. It was John Guyse Kinsman, for example, who outlined the method of entry.

38] National Archives.

39] England and Wales Marriages 1837-2005, ancestry.com

40] England and Wales, Civil Registration Death Index 1837-1915, ancestry.com

41] Victoria Police Gazette, June 13, 1871.

42] Convict Transportation Registers.

43] Victoria Police Gazette, June 13, 1871.

44] Western Australia Death Index.

45] 1861 Census.

46] Wills or Administrations after 1858 – National Archives.

47] 1861 Census.

48] 1891 Census.

49] England and Wales, Civil Registration Index, ancestry.com

50] England and Wales Deaths 1837-2007, findmypast.co.uk

51] 1901 Census.

52] United States Marriages.

53] 1910 United States Census.

54] Yorkshire Post and Intelligencer, Tuesday, April 9, 1878.

* All newspaper images are from:

British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

1] Yorkshire Post and Intelligencer, Tuesday, April 9, 1878.

2] The burglary received coverage across the country in newspapers ranging from the Hampshire Advertiser to the Dundee, Perth, Forfar, and Fife People’s Journal.

3] Field, J. (1972) English Field Names: a Dictionary. David and Charles, Newton Abbot, P.153.

4] West Yorkshire Archive Service WDP26/3/21. Extract from deed of bargain and sale 13 Mar 1793.

5] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

6] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

7] In 1858 banknotes would be very difficult to convert into cash, particularly so for those at the lower end of society who would probably have to “fence” them at a considerable discount.

8] Morning Advertiser, Friday, March 5, 1858.

9] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

10] Leeds Intelligencer, March 6, 1858.

11] Leeds Intelligencer, March 6, 1858.

12] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

13] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

14] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

15] The life preserver consisted of a sturdy length of cane about 12 inches long. At one end was a knob consisting of 5 or 6 ounces of lead, at the other, a loop of leather strapping to secure it to the user’s wrist. Somewhat ironically, the life preserver became a popular self-defense device in the wake of the Garotte robberies that were prevalent in 1850s England.

16] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

17] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

18] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, May 8, 1858

19] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Wednesday, May 5, 1858.

20] Leeds Times, May 15, 1858.

21] The Royal Alhambra Museum and Promenade Concert Hall “the palace of cheap and rational amusement for the people” was situated in King Charles’s Croft, Leeds.

22] Leeds Times, May 24, 1858.

23] Taylor, D. (1998) Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914. Macmillan Press, Basingstoke, P.78.

24] The Leeds Times, December 6, 1858, reported that Mr. Wilson Overend, chairman of the West Riding Quarter Sessions, ‘referred to the great increase of crime in the district, and to the ill effects attendant upon the release of convicts upon tickets-of-leave.’

25] Taylor, D. (1998) Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750-1914. Macmillan Press, Basingstoke. P.78.

26] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

27] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

28] The Hook sisters claimed to have been struck by life preservers during the robbery, though no injuries appear to have been reported at the trial.

29] Supplement to the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, March 21, 1857.

30] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

31] The Sheffield Daily Telegraph uses the spelling ”Gledall” though prison documents use Gleadall.

32] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

33] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

34] Supplement to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Monday, March 15, 1858.

35] Intelligencer Supplement, Leeds, March 6, 1858.

36] Prison Register Correspondence and Warrants.

37] It should also be borne in mind that the entire narrative of the burglary is based upon evidence provided by the victims. It was John Guyse Kinsman, for example, who outlined the method of entry.

38] National Archives.

39] England and Wales Marriages 1837-2005, ancestry.com

40] England and Wales, Civil Registration Death Index 1837-1915, ancestry.com

41] Victoria Police Gazette, June 13, 1871.

42] Convict Transportation Registers.

43] Victoria Police Gazette, June 13, 1871.

44] Western Australia Death Index.

45] 1861 Census.

46] Wills or Administrations after 1858 – National Archives.

47] 1861 Census.

48] 1891 Census.

49] England and Wales, Civil Registration Index, ancestry.com

50] England and Wales Deaths 1837-2007, findmypast.co.uk

51] 1901 Census.

52] United States Marriages.

53] 1910 United States Census.

54] Yorkshire Post and Intelligencer, Tuesday, April 9, 1878.