“A Regular Place of Entertainment for the Poorer Classes”: (1)

Gildersome’s Workhouse 1777-1869

by Andrew Bedford © 2018

**Updated 28 Sep 2018**

Gildersome’s Workhouse 1777-1869

by Andrew Bedford © 2018

**Updated 28 Sep 2018**

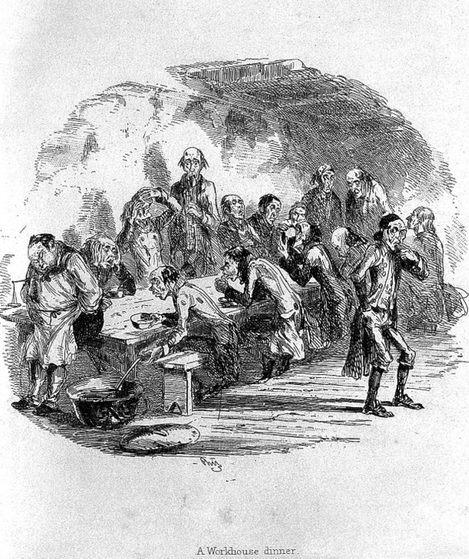

Satirical depiction of poor people having dinner in a workhouse, 1840 - courtesy of Wellcome L0006801.jpg

Satirical depiction of poor people having dinner in a workhouse, 1840 - courtesy of Wellcome L0006801.jpg

In the same year that Oliver Twist was published, The Leeds Times issued its own revelations about the ‘disgraceful treatment of paupers’ in a ‘wretched and filthy workhouse.’(2) It may be something of an understatement to say that discovering that this establishment had been situated in the village in which I grew up took me by surprise. Subsequent research confirmed that my first address was situated just a few doors away from where Gildersome’s workhouse had once cast its forbidding shadow. It would later transpire that St Mary’s Hospital, in which I made my entry into the world, had originally been the Bramley Union Workhouse, built to accommodate (among others) Gildersome’s paupers after 1872. Furthermore, my daughter was born at Staincliffe Hospital: formerly the Dewsbury Union Workhouse in which Gildersome’s poor had been accommodated after 1925. All of which leads me to reflect that my formative years appear to have been spent, if not literally within the shadow of the workhouse, then within the shadow of the shadow of the workhouse. It is from this perspective that the following will attempt to recover the histories of Gildersome’s workhouse within a context of nineteenth-century political legislation and philosophical debate.

The Poor Law of 1601 had obliged townships throughout the country to make provision for the poor by means of a local poor rate. That Gildersome had complied with this legislation becomes evident when we find that Gilbert’s Parliamentary Survey of the Overseers of the Poor (1777) listed Gildersome as having a parish workhouse housing up to twenty inmates.(3) At the time Gildersome was a township within Batley Parish, so the survey might have more accurately listed Gildersome as having a “township workhouse.” In order to avoid further confusion, it might be helpful to bear in mind that in the North of England the term “poorhouse” tended to be used rather than “workhouse.”(4) Prior to the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, it had been customary to establish poorhouses in ‘converted domestic buildings’(5) and it seems likely that this had been the case at Gildersome.

The Poor Law of 1601 had obliged townships throughout the country to make provision for the poor by means of a local poor rate. That Gildersome had complied with this legislation becomes evident when we find that Gilbert’s Parliamentary Survey of the Overseers of the Poor (1777) listed Gildersome as having a parish workhouse housing up to twenty inmates.(3) At the time Gildersome was a township within Batley Parish, so the survey might have more accurately listed Gildersome as having a “township workhouse.” In order to avoid further confusion, it might be helpful to bear in mind that in the North of England the term “poorhouse” tended to be used rather than “workhouse.”(4) Prior to the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, it had been customary to establish poorhouses in ‘converted domestic buildings’(5) and it seems likely that this had been the case at Gildersome.

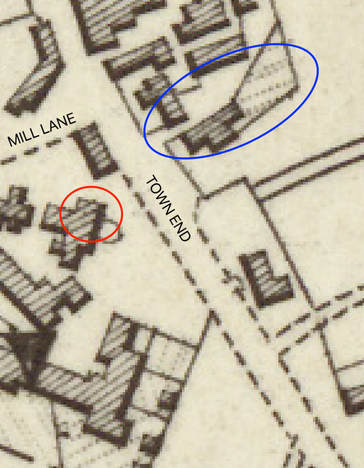

The location of Gildersome’s principal poorhouse is suggested in the census returns of 1841, 1851 and 1861 as being close to the Town End or Town Green area. The census returns for 1851 and 1861 also appear to suggest that more than one address had been designated “poorhouse”. In his History of Gildersome and the Booth Family, PH Booth asserts that the workhouse was located ‘nearly opposite the Miners’ Arms’(6) and the Ordnance Survey Map of 1852 shows two buildings that potentially fulfil Booth’s criteria (see above left). Both would have been accessed via an entrance situated ‘nearly opposite the Miners’ Arms’ (the red circle) and both are positioned on what is defined on the 1851 sale map (above right) as ‘The Parish’ (a common term of reference for the poorhouse). The area of cultivated land by the side of the lower of those buildings (within the blue circle) is also suggestive of a rural poorhouse in which inmates would be expected to supplement their upkeep with produce grown on the premises. Research has confirmed that both buildings in the blue circle had indeed been occupied by the Overseers of the Poor and used as workhouse premises. These had been acquired in 1808 by William Hudson, James Bilbrough and John Bilbrough. A tax assessment for the township of Gildersome dated 1815 corroborates this by asserting that the workhouse in Gildersome was in the possession of Messrs Hudson and Company. (7) The upper of those buildings was a former dwelling house and the lower a combination of barn and stables with a garden or croft attached. It may be reasonable to hypothesize, therefore, that the inmates would have been housed in the former and put to work in the latter.

Ordnance Survey of 1852

Ordnance Survey of 1852

Added to which, a deed registered in 1850 states that two cottages at Harthill Lane Bottom (pictured above right) had been erected at the expense of the inhabitants of Gildersome many years ago and ‘are now in the possession of the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of Gildersome’. Census returns confirm that these properties were inhabited by elderly paupers. The 1861 census also lists a similar property close to the Woodman's Inn, suggesting that capacity was periodically increased to meet fluctuating requirements. We might reasonably infer, therefore, that a Township poorhouse built before 1777 with a capacity for no more than twenty inmates was supplemented by extra accommodation provided by public subscription in response to the gathering expansion of industrialisation and an increasing population.

Having established the location, it might be useful to consider the context within which Gildersome’s poorhouse would have operated. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 and the political philosophies that informed it were heavily satirised by Charles Dickens in Oliver Twist. The Act had been passed in an era of economic turbulence and increasing demand for poor relief. It also developed against a backdrop of political and philosophical debate. Key to this debate was the concept that poverty was a natural condition of society and that society was therefore dependant upon it for its wellbeing. Edmund Burke, for example, in 1797, had warned that ‘when we affect to pity, as poor, those who must labour or the world cannot exist, we are trifling with the condition of mankind.’(8) Jeremy Bentham also underlined the inevitability of poverty when he stated that ‘as labour is the source of all wealth, so poverty is of labour.’(9) Similar sentiments were expressed in the writings of political economists Thomas Malthus (1796) and David Ricardo (1817) who both argued that the Poor Law of 1601 had effectively encouraged pauperism and both had called for the outright abolition of poor relief.(10) The Amendment Act, therefore, can be seen as a conciliatory piece of legislation that sought to reduce the economic burden of pauperism (for ratepayers) by creating a system of poor relief that would deter all but those in the most extreme circumstances, while falling short of abolishing poor relief altogether.

The 1851 census for Gildersome lists five residents in the town poorhouse and twenty-three people in receipt of out relief. When we consider that the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 demanded that everyone, including the able bodied, should be compelled to enter the workhouse in order to receive relief, we can infer that Gildersome had chosen not to implement the Act. The Amendment Act placed the workhouse at the focal point of poor relief, with the intention of creating conditions that would ‘deter all but the most necessitous from applying for relief.’(11) Hence, there was a requirement for larger, purpose-built workhouses in which all applicants might be accommodated. The Act also required that paupers were segregated. On entering the new workhouses, families were separated into male and female wards. Pauper children were perceived as being in particular need of rescue and reform; to which end they were separated from parents who had already demonstrated their unfitness to parent by their descent into pauperism. The new workhouses, or “Bastilles” as they quickly became known, were specifically designed and operated to foster the idea of a place of last resort, ‘a grim place from which the poor would do well to stay away.’(12) That Gildersome persisted with its traditional combination of local poorhouse and out relief is perhaps reflective of the economic realities of the West Riding of Yorkshire in the early nineteenth century. In an economy characterised by cycles of boom and bust, during regular periods of severe economic downturn even applications restricted to the “most necessitous” would have required accommodation beyond the means of Gildersome’s ratepayers.

This is not to suggest, however, that provision for the township’s poor had remained unchanged since 1601 or that the township was unduly lenient with its paupers. Thomas Gilbert’s Act of 1782 had been postulated with two underpinning aims: to ‘accommodate the vulnerable and to make the workhouse economically viable by working the poor as much as possible.’(13) Gilbert’s Act placed emphasis on finding work for and making outdoor relief payments to able-bodied claimants, while housing the young, the aged and infirm within the workhouse. The work provided was intended to be hard and included stone breaking and road building to maintain the local roads.(14) There is evidence to suggest that Gildersome’s overseers put the unemployed to work in this way. In 1828 a stone kiln was erected close to the colliery on Street Lane to process stone for road building.(15) One way in which townships could circumvent the Poor Law Amendment Act was by providing out-relief from the highway rate rather than the poor rate. It becomes evident, therefore, that census returns may not provide a full and reliable account of people in receipt of poor relief. The Gilbert Act also offered the option for parishes to combine resources in order to create larger workhouses in which relief could be provided more cost effectively. However, the creation of such unions was not mandatory and parishes and townships were able to adopt Gilbert’s system unilaterally, thereby managing poor relief more economically, while still retaining local autonomy.(16) By adhering to Gilbert’s model of poor relief after 1834, the township of Gildersome had effectively rejected the recommendations implied in the Poor Law Amendment Act and, in doing so, avoided interference from the London-based Poor Law Commissioners.

The management of Gildersome’s poor relief was underpinned by the requirement to observe the ‘strictest frugality in dispensing the public money.’(17) Another piece of legislation that promised increased efficiency in administering poor relief was Sturges Bourne’s Act of 1819. This enabled parishes and townships to switch from a system of “open vestry” in which all ratepayers were entitled to attend vestry meetings and voice their opinions, to an elected or “select vestry” that made administrative decisions on behalf of the ratepayers. It becomes evident that Gildersome had adopted Sturges Bourne’s recommendations when we find that in 1820 a ‘select vestry’ had been duly elected ‘for the management of the poor, agreeable to an Act passed in the last session of the late Parliament.’(18) However, the system also offered significant opportunity for malpractice and corruption, and appears to have been already regarded as something of a national scandal at the time of its inauguration at Gildersome.(19) Gildersome’s inaugural select vestry was comprised of ‘fifteen substantial housekeepers in the Township of Gildersome’: Matthew Stephenson, John Buttrey, Thomas Gilpin, Joseph Geldert, George Beevers, Isaac Gilpin, Mr Clark, John Benn, Mr. Elam, John Richardson, Mr. Hudson, John Ellis, James Bilbrough, Richard Lindsey and John Westerman.(20) It may be worth drawing attention to the fact that two members of the appointed vestry were also owners of the workhouse premises.

Along with the select vestry, Sturges Bourne’s act also enabled Gildersome to appoint an assistant overseer: a salaried employee ‘whose main tasks were inspecting the poor and distributing relief.’(21) The assistant overseer effectively assumed a role similar to that undertaken by the “master or matron” (or both) of the larger Poor Law Amendment Act workhouses, though at a considerably reduced rate of remuneration. The appointment of a salaried official would be expected to set the management of poor relief on a more professional footing, thus offering additional financial reassurance to the township’s ratepayers.

The 1851 census for Gildersome lists five residents in the town poorhouse and twenty-three people in receipt of out relief. When we consider that the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 demanded that everyone, including the able bodied, should be compelled to enter the workhouse in order to receive relief, we can infer that Gildersome had chosen not to implement the Act. The Amendment Act placed the workhouse at the focal point of poor relief, with the intention of creating conditions that would ‘deter all but the most necessitous from applying for relief.’(11) Hence, there was a requirement for larger, purpose-built workhouses in which all applicants might be accommodated. The Act also required that paupers were segregated. On entering the new workhouses, families were separated into male and female wards. Pauper children were perceived as being in particular need of rescue and reform; to which end they were separated from parents who had already demonstrated their unfitness to parent by their descent into pauperism. The new workhouses, or “Bastilles” as they quickly became known, were specifically designed and operated to foster the idea of a place of last resort, ‘a grim place from which the poor would do well to stay away.’(12) That Gildersome persisted with its traditional combination of local poorhouse and out relief is perhaps reflective of the economic realities of the West Riding of Yorkshire in the early nineteenth century. In an economy characterised by cycles of boom and bust, during regular periods of severe economic downturn even applications restricted to the “most necessitous” would have required accommodation beyond the means of Gildersome’s ratepayers.

This is not to suggest, however, that provision for the township’s poor had remained unchanged since 1601 or that the township was unduly lenient with its paupers. Thomas Gilbert’s Act of 1782 had been postulated with two underpinning aims: to ‘accommodate the vulnerable and to make the workhouse economically viable by working the poor as much as possible.’(13) Gilbert’s Act placed emphasis on finding work for and making outdoor relief payments to able-bodied claimants, while housing the young, the aged and infirm within the workhouse. The work provided was intended to be hard and included stone breaking and road building to maintain the local roads.(14) There is evidence to suggest that Gildersome’s overseers put the unemployed to work in this way. In 1828 a stone kiln was erected close to the colliery on Street Lane to process stone for road building.(15) One way in which townships could circumvent the Poor Law Amendment Act was by providing out-relief from the highway rate rather than the poor rate. It becomes evident, therefore, that census returns may not provide a full and reliable account of people in receipt of poor relief. The Gilbert Act also offered the option for parishes to combine resources in order to create larger workhouses in which relief could be provided more cost effectively. However, the creation of such unions was not mandatory and parishes and townships were able to adopt Gilbert’s system unilaterally, thereby managing poor relief more economically, while still retaining local autonomy.(16) By adhering to Gilbert’s model of poor relief after 1834, the township of Gildersome had effectively rejected the recommendations implied in the Poor Law Amendment Act and, in doing so, avoided interference from the London-based Poor Law Commissioners.

The management of Gildersome’s poor relief was underpinned by the requirement to observe the ‘strictest frugality in dispensing the public money.’(17) Another piece of legislation that promised increased efficiency in administering poor relief was Sturges Bourne’s Act of 1819. This enabled parishes and townships to switch from a system of “open vestry” in which all ratepayers were entitled to attend vestry meetings and voice their opinions, to an elected or “select vestry” that made administrative decisions on behalf of the ratepayers. It becomes evident that Gildersome had adopted Sturges Bourne’s recommendations when we find that in 1820 a ‘select vestry’ had been duly elected ‘for the management of the poor, agreeable to an Act passed in the last session of the late Parliament.’(18) However, the system also offered significant opportunity for malpractice and corruption, and appears to have been already regarded as something of a national scandal at the time of its inauguration at Gildersome.(19) Gildersome’s inaugural select vestry was comprised of ‘fifteen substantial housekeepers in the Township of Gildersome’: Matthew Stephenson, John Buttrey, Thomas Gilpin, Joseph Geldert, George Beevers, Isaac Gilpin, Mr Clark, John Benn, Mr. Elam, John Richardson, Mr. Hudson, John Ellis, James Bilbrough, Richard Lindsey and John Westerman.(20) It may be worth drawing attention to the fact that two members of the appointed vestry were also owners of the workhouse premises.

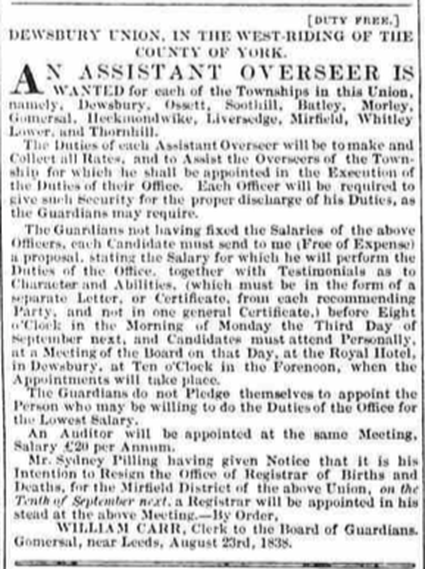

Along with the select vestry, Sturges Bourne’s act also enabled Gildersome to appoint an assistant overseer: a salaried employee ‘whose main tasks were inspecting the poor and distributing relief.’(21) The assistant overseer effectively assumed a role similar to that undertaken by the “master or matron” (or both) of the larger Poor Law Amendment Act workhouses, though at a considerably reduced rate of remuneration. The appointment of a salaried official would be expected to set the management of poor relief on a more professional footing, thus offering additional financial reassurance to the township’s ratepayers.

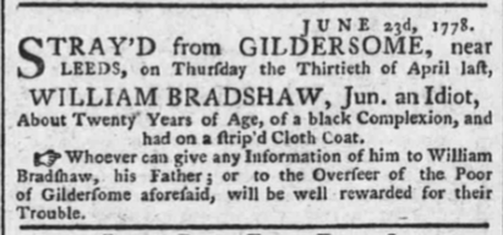

Leeds Intelligencer 1778

Leeds Intelligencer 1778

Care of the mentally ill routinely fell to the mercy of the overseers of the poor, as an advert from 1778 (right) demonstrates. In 1836, however, Gildersome Township was charged with failing to provide a list of “lunatics” to the Clerk of the Peace,(22) which suggests that effective management had not necessarily been achieved by the appointment of an assistant overseer. Added to which, the case of an inmate by the name of William Oddy provides further insight into the way that Gildersome’s workhouse was being managed. It stands to reason that the mentally unstable were likely to be a considerable cause of disruption within the workhouse and it was expected that the more troublesome would be identified and transferred to the county asylum.(23) The additional cost of maintaining a pauper in the West Riding Paupers’ Lunatic Asylum was, however, prohibitive and there was considerable temptation for relieving officers to record “lunatics” as harmless in order to reduce the township’s expenditure (or, indeed, not to record them at all). Whether William Oddy would have figured on Gildersome Township’s “list of lunatics” remains a matter of conjecture, though the possibility of mental instability is suggested by the following incidents. Quoting from the Select Vestry Minutes of 1827, Booth reports that the assistant overseer had been instructed to take out a warrant against William Oddy should he continue to misbehave in the workhouse.(24) Whether a warrant was actually taken out is not recorded, though a newspaper report from 1838 indicates that the problem of William Oddy’s misbehaviour had been finally resolved when that unfortunate gentlemen was severely burnt and removed to the Infirmary where he ‘languished in the most excruciating misery’ until he expired.(25) A verdict of accidental death was duly recorded.

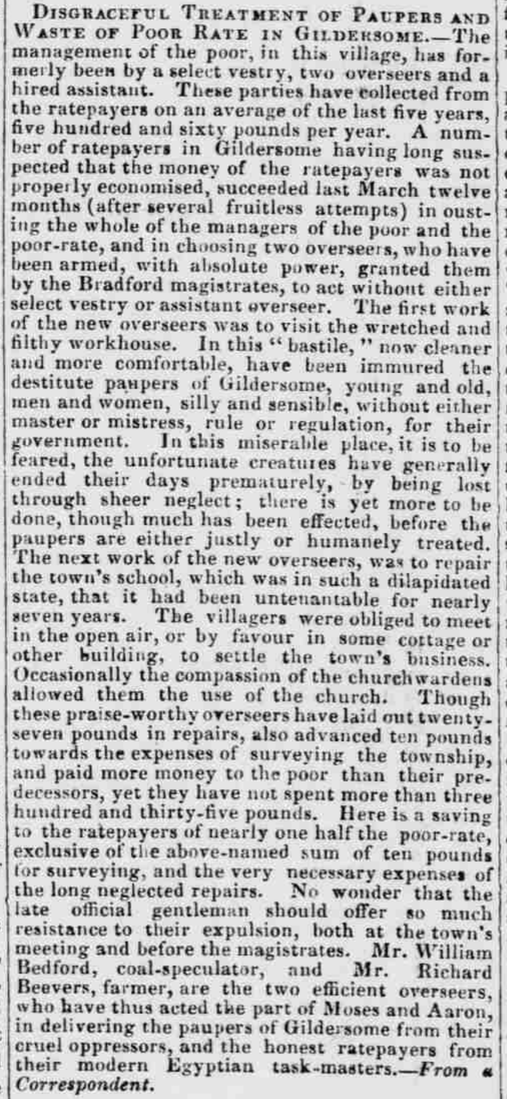

Leeds Times, April 21, 1838

Leeds Times, April 21, 1838

Despite the Coroner’s verdict, however, the conditions in which Mr Oddy had met with his demise and the management of Gildersome’s poorhouse were brought into uncomfortable focus by revelations about the ‘disgraceful treatment’ of paupers in Gildersome that were to emerge some weeks later. According to the Leeds Times, ‘the destitute paupers of Gildersome’ had been incarcerated within a ‘wretched and filthy workhouse’ in conditions so squalid that the inmates ended their days prematurely through sheer neglect.(26) The article also argues that the poor rate had been grossly mismanaged and relates how the select vestry and assistant overseer had been removed from office and replaced by ‘two efficient overseers.’(27) Mr William Bedford and Mr Richard Beevers are credited with acting the part of ‘Moses and Aaron’ in ‘delivering the paupers of Gildersome from their cruel oppressors, and the honest ratepayers from their modern Egyptian taskmasters.’ It appears, then, that the newly appointed overseers had not only rescued the township’s paupers, they had, in keeping with contemporary political philosophy, managed to do so at a substantial saving to the ratepayers. However, in spite of the gallant, if not to say divine, intervention of “Moses and Aaron,” a few years later it seems that the old system was back up and running.

Considerable savings could be made to poor rate expenditure by returning paupers to the place of their birth, thereby removing the burden of relief from their residential township. In 1855 Joseph Shaw, assistant overseer for the Township of Gildersome, and Benjamin Clapham, one of the select vestry for the same township, were charged with unlawfully inducing recently widowed Elizabeth Myland and her two children to remove to Leeds, where, they told her, she would be closer to her relatives. However, it seems that the ulterior motive was to transfer the cost of Mrs Myland’s upkeep to the Leeds Board of Guardians. It appears, on this occasion, that Gildersome’s officials had crossed the line that divides fiscal prudence and fraud. While Clapham was released without conviction, the charges against Joseph Shaw were proved and he was fined £5.(28) Such was Joseph Shaw’s dedication to his post of assistant overseer it had apparently induced him to place the township’s requirements ahead of those of the legal system.

Considerable savings could be made to poor rate expenditure by returning paupers to the place of their birth, thereby removing the burden of relief from their residential township. In 1855 Joseph Shaw, assistant overseer for the Township of Gildersome, and Benjamin Clapham, one of the select vestry for the same township, were charged with unlawfully inducing recently widowed Elizabeth Myland and her two children to remove to Leeds, where, they told her, she would be closer to her relatives. However, it seems that the ulterior motive was to transfer the cost of Mrs Myland’s upkeep to the Leeds Board of Guardians. It appears, on this occasion, that Gildersome’s officials had crossed the line that divides fiscal prudence and fraud. While Clapham was released without conviction, the charges against Joseph Shaw were proved and he was fined £5.(28) Such was Joseph Shaw’s dedication to his post of assistant overseer it had apparently induced him to place the township’s requirements ahead of those of the legal system.

Leeds Intelligencer, Sept 1, 1838

Leeds Intelligencer, Sept 1, 1838

Mr Shaw’s unswerving commitment to the interests of his employers is further illustrated in the following episode. In 1859 the Board of Guardians at the Rochdale Union complained that £5 12s 6d had been expended on relieving a family from Gildersome and that the overseers of that township had exploited a legal loophole in order to avoid reimbursement. A further claim for the same family forwarded to Gildersome for £1 2s 6d had also been disregarded until, after repeated applications, Mr Joseph Shaw, the assistant overseer of Gildersome’s “shabby union” had contacted the Rochdale Union to explain that he had been unable to travel to the bank in Leeds because of the wet weather. Mr Shaw went on to reassure the Rochdale Guardians that the money would be paid at the earliest opportunity.(29)(30)

The position of assistant overseer carried considerable responsibility, though it has been suggested that more capable candidates were often deterred by low wages and poor working conditions. On the other hand, the position offered considerable opportunity for those so inclined, to supplement their incomes by dubious means.(31) It has also been suggested that those seeking employment in this area might have been tempted to exaggerate their qualifications and, with this in mind, the census returns make for interesting reading. In 1851, Joseph Shaw (28) is listed as living at Gildersome Street and employed as a woolsorter.(32) In 1858, White’s Directory lists Shaw as a farmer and assistant overseer.(33) By 1861 Joseph Shaw (38) has moved down the road to Street Lane and is listed as a “schoolmaster”; his wife Sarah is listed as “schoolmaster’s wife”. As assistant overseer, part of Shaw’s responsibilities would have been to provide some form of rudimentary education for the poorhouse children. Many rural townships provided three hours of schooling per day and ‘legislation in 1845 insisted that pauper apprentices be able to read their indenture papers and to write their signatures on it.’(34) The employment of township schoolmasters was curtailed around 1870 when the local elementary or Board schools were introduced and pauper children were absorbed into mainstream education.(35) Beyond 1870, it appears that Shaw’s teaching qualifications were no longer the asset they had once been. Hence, in 1871, the Shaws are listed as innkeepers (New Inn) and by 1881 Joseph and Sarah Shaw were greengrocers at Heckmondwike. It might be reasonably suggested that Shaw’s transformation from “woolsorter” to “schoolmaster” reveals more about the standards required by Gildersome Township than it did about Shaw’s academic competences. Shaw’s occupations in 1871 and 1881 also suggest that he had been able to make provision for his later years in spite of his poorly paid position as assistant overseer.

Education was seen as a key component in the effort to reduce pauperism and, aside from the provision afforded by the Township of Gildersome, a workhouse school had been commissioned in 1772 by the Society of Friends. Unlike their counterparts in the township, the Gildersome Friends claimed to provide a ‘master of character and conduct … well qualified to teach reading, writing and accompts’ along with a ‘large commodious house’ set within ‘fifty acres of land’.(36) At this establishment the children of poor Friends who were deemed to be “proper objects” for relief were provided with food and lodging, as well as education. As with their counterparts at the township, they were also expected to work for three or four hours every day in support of their provision. When their education was deemed to be complete, the “proper objects” were apprenticed to various trades and callings within the wider Quaker community.

The position of assistant overseer carried considerable responsibility, though it has been suggested that more capable candidates were often deterred by low wages and poor working conditions. On the other hand, the position offered considerable opportunity for those so inclined, to supplement their incomes by dubious means.(31) It has also been suggested that those seeking employment in this area might have been tempted to exaggerate their qualifications and, with this in mind, the census returns make for interesting reading. In 1851, Joseph Shaw (28) is listed as living at Gildersome Street and employed as a woolsorter.(32) In 1858, White’s Directory lists Shaw as a farmer and assistant overseer.(33) By 1861 Joseph Shaw (38) has moved down the road to Street Lane and is listed as a “schoolmaster”; his wife Sarah is listed as “schoolmaster’s wife”. As assistant overseer, part of Shaw’s responsibilities would have been to provide some form of rudimentary education for the poorhouse children. Many rural townships provided three hours of schooling per day and ‘legislation in 1845 insisted that pauper apprentices be able to read their indenture papers and to write their signatures on it.’(34) The employment of township schoolmasters was curtailed around 1870 when the local elementary or Board schools were introduced and pauper children were absorbed into mainstream education.(35) Beyond 1870, it appears that Shaw’s teaching qualifications were no longer the asset they had once been. Hence, in 1871, the Shaws are listed as innkeepers (New Inn) and by 1881 Joseph and Sarah Shaw were greengrocers at Heckmondwike. It might be reasonably suggested that Shaw’s transformation from “woolsorter” to “schoolmaster” reveals more about the standards required by Gildersome Township than it did about Shaw’s academic competences. Shaw’s occupations in 1871 and 1881 also suggest that he had been able to make provision for his later years in spite of his poorly paid position as assistant overseer.

Education was seen as a key component in the effort to reduce pauperism and, aside from the provision afforded by the Township of Gildersome, a workhouse school had been commissioned in 1772 by the Society of Friends. Unlike their counterparts in the township, the Gildersome Friends claimed to provide a ‘master of character and conduct … well qualified to teach reading, writing and accompts’ along with a ‘large commodious house’ set within ‘fifty acres of land’.(36) At this establishment the children of poor Friends who were deemed to be “proper objects” for relief were provided with food and lodging, as well as education. As with their counterparts at the township, they were also expected to work for three or four hours every day in support of their provision. When their education was deemed to be complete, the “proper objects” were apprenticed to various trades and callings within the wider Quaker community.

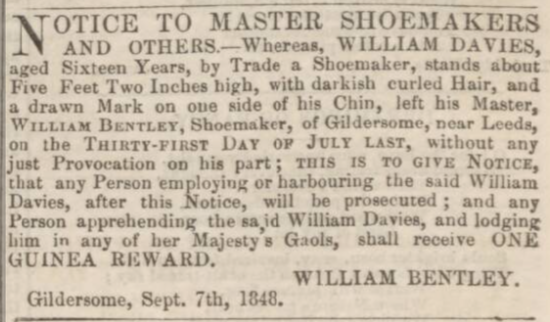

Leeds Times, Sept 9, 1848

Leeds Times, Sept 9, 1848

Apprenticeships had also formed an underpinning element of mainstream Poor Law policies, with both boys and girls being indentured to local tradesmen by the Gildersome Township. During the early 1800s, clothiers and shoemakers were among the foremost of Gildersome’s local industries; in 1838 it was estimated that there were around 120 handloom weavers still operating in Gildersome.(37) However, as industrialisation continued to gather pace, the old trades began to decline and with them the opportunities for meaningful apprenticeships.

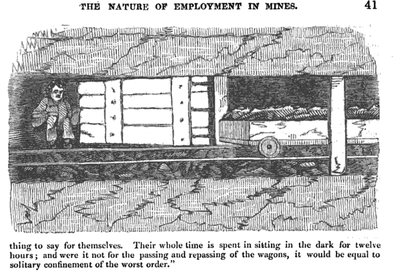

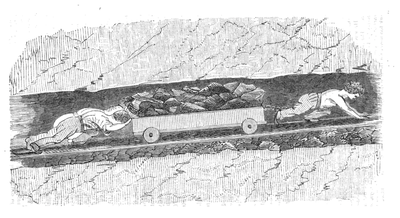

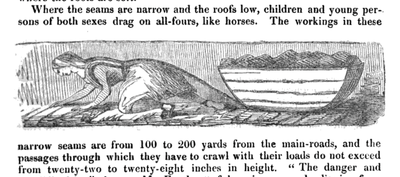

As the handloom weavers were going into decline, Gildersome’s coal mining industry was continuing to expand. During the early part of the nineteenth century it was customary for colliers to take their children into the mines as soon as they were able to contribute to the family income. A collier’s earnings could be usefully supplemented by the few pence per week children as young as five could earn by “trapping”: a system of opening and closing gates devised to improve ventilation underground. Older and stronger children were employed as “hurriers”: a job that involved hauling tubs of coal from the coalface to the shaft. For those colliers with no children of their own the solution resided at the poorhouse. Thomas Reyner, a surgeon at Birstall, confirmed that it was the ‘practice of the colliers or masters who want children to go to the board room and get an order to take a child after they have picked them out of the workhouse.’(38) This somewhat Dickensian scenario is further illustrated when Reyner goes on to say that workhouse children were not allowed to be bound before the age of ten, though it was common practice to send younger children out on “trial”. Reyner cited the case of a child at the Batley workhouse who was put out on trial with a collier sometime before his fifth birthday. The child in question was rescued at the intercession of his uncle. Had this not been the case, the child’s prospects would have been bleak. In their report on coal mining in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Employment Commission complained that parish apprentices were ‘bound to serve their masters till twenty one years of age, in an employment in which there is nothing of skill to be acquired, under circumstances of frequent ill-treatment, and under the oppressive condition that they shall receive only food and clothing, while their free companions may be obtaining a man’s wages.’(39)

As the handloom weavers were going into decline, Gildersome’s coal mining industry was continuing to expand. During the early part of the nineteenth century it was customary for colliers to take their children into the mines as soon as they were able to contribute to the family income. A collier’s earnings could be usefully supplemented by the few pence per week children as young as five could earn by “trapping”: a system of opening and closing gates devised to improve ventilation underground. Older and stronger children were employed as “hurriers”: a job that involved hauling tubs of coal from the coalface to the shaft. For those colliers with no children of their own the solution resided at the poorhouse. Thomas Reyner, a surgeon at Birstall, confirmed that it was the ‘practice of the colliers or masters who want children to go to the board room and get an order to take a child after they have picked them out of the workhouse.’(38) This somewhat Dickensian scenario is further illustrated when Reyner goes on to say that workhouse children were not allowed to be bound before the age of ten, though it was common practice to send younger children out on “trial”. Reyner cited the case of a child at the Batley workhouse who was put out on trial with a collier sometime before his fifth birthday. The child in question was rescued at the intercession of his uncle. Had this not been the case, the child’s prospects would have been bleak. In their report on coal mining in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Employment Commission complained that parish apprentices were ‘bound to serve their masters till twenty one years of age, in an employment in which there is nothing of skill to be acquired, under circumstances of frequent ill-treatment, and under the oppressive condition that they shall receive only food and clothing, while their free companions may be obtaining a man’s wages.’(39)

Click on the sideshow above to see contemporary examples of the "oppressive conditions" of child colliery workers. Hurriers were employed to move corves (coal wagons) from the coalface to the shaft. In collieries working thick coal seams, ponies were used; in Gildersome’s narrow seams, children were better suited to navigate galleries that could be as little as twenty-four inches in height.

The 1841 census for Gildersome has boys of ten and eleven years of age listed as apprentice coalminers and the Children’s Employment Commission (1842) provides further evidence of pauper apprentices working in Gildersome’s collieries. William Colling, underground steward at Smith’s colliery affirmed that ‘we have only three or four colliers who take apprentices and keep them and they have others to hurry for them.’(40) Ann Wilson, a hurrier(41) at the same colliery presents a revealing example of contemporary employment practices when she states that ‘I live with Brown who keeps me and not with my father and I hurry for one of the apprentice lads.’(42) From a modern perspective, it may be somewhat sobering to consider that Ann Wilson was ten years old when she made her statement to the commission.

Colliery owner, William Bedford, the “Moses” who had previously rescued Gildersome’s paupers from their “oppressors” and the ratepayers from their “Egyptian taskmasters” offered his own words of wisdom to the commission. Speaking about the practice of keeping children underground to complete their work after the men had finished their shifts, Bedford confirmed that children ‘go to the pits between 7 and 8 years old and some younger. They sometimes are trappers but oftener hurriers … it is a bad place to allow children to stay in the pits to work after the men have left. The lads do nothing but play and are in far too long.’(43) Given that Mr. Bedford was an overseer of the poor, the sentiments expressed appear to offer little by way of comfort for Gildersome’s “Isrealites.”

The 1841 census for Gildersome has boys of ten and eleven years of age listed as apprentice coalminers and the Children’s Employment Commission (1842) provides further evidence of pauper apprentices working in Gildersome’s collieries. William Colling, underground steward at Smith’s colliery affirmed that ‘we have only three or four colliers who take apprentices and keep them and they have others to hurry for them.’(40) Ann Wilson, a hurrier(41) at the same colliery presents a revealing example of contemporary employment practices when she states that ‘I live with Brown who keeps me and not with my father and I hurry for one of the apprentice lads.’(42) From a modern perspective, it may be somewhat sobering to consider that Ann Wilson was ten years old when she made her statement to the commission.

Colliery owner, William Bedford, the “Moses” who had previously rescued Gildersome’s paupers from their “oppressors” and the ratepayers from their “Egyptian taskmasters” offered his own words of wisdom to the commission. Speaking about the practice of keeping children underground to complete their work after the men had finished their shifts, Bedford confirmed that children ‘go to the pits between 7 and 8 years old and some younger. They sometimes are trappers but oftener hurriers … it is a bad place to allow children to stay in the pits to work after the men have left. The lads do nothing but play and are in far too long.’(43) Given that Mr. Bedford was an overseer of the poor, the sentiments expressed appear to offer little by way of comfort for Gildersome’s “Isrealites.”

Dickens, C. (1838) Oliver Twist. Oxford: University Press, p. 23

Dickens, C. (1838) Oliver Twist. Oxford: University Press, p. 23

In Dickens’ fictional Parish, Oliver Twist narrowly avoided being apprenticed to a chimneysweep after unaccustomed compassion had been evoked by the child’s distress. It seems evident from the sentiments expressed by William Bedford that, had he resided at Gildersome’s poorhouse, Oliver may not have been quite so fortunate. Given that Oliver’s fictional birth had taken place some time before 1834, Dickens’ satirical attack on the Poor Law Amendment Act was confused to some extent by his depiction of a workhouse that would have been operating under an earlier system. We have seen that Gildersome Township chose to operate under an earlier system and it may be pertinent to consider why this was the case. The Poor Law Amendment Act had sought to deter all but the utterly destitute from applying for poor relief by creating workhouse conditions that were demonstrably less congenial than those available outside. The Royal Commissioners’ Report into the Collieries of the West Riding makes it evident, however, that Gildersome’s overseers would have been hard pressed to create poorhouse conditions that were even remotely as harsh as those experienced in the collieries. As we have seen above, Gildersome’s poorhouse was hardly a “regular place of entertainment” and its conditions were occasionally the focus of public rebuke, so we might reliably infer that the reasons for not implementing the act were not based on benevolence. I would suggest that the reason Gildersome chose not to implement the Poor Law Amendment Act, until compelled to do so by an act of parliament, was based on the familiar combination of financial caution and Yorkshire cussedness, which, some might say, boil down to pretty much the same thing.

In 1869, legislation was passed in parliament ordering the dissolution of the remaining Gilbert Unions, resulting in Gildersome Township, along with those of Armley, Farnley and Wortley, being absorbed into the newly formed Bramley Union.(44) Gildersome remained part of the Bramley Union until 1925 when further reorganisation resulted in its affiliation with the Dewsbury Union, where it remained until the workhouse system was dismantled in 1930. Following its absorption into the Bramley Union, Gildersome’s workhouse found itself surplus to requirements. The barn and stables building was demolished to make way for the Methodist chapel around 1880. The principal building was converted into cottages around the same time. These cottages were still occupied in 1939 (part of Clayton Fold) and probably demolished sometime during the 1940s.

In 1869, legislation was passed in parliament ordering the dissolution of the remaining Gilbert Unions, resulting in Gildersome Township, along with those of Armley, Farnley and Wortley, being absorbed into the newly formed Bramley Union.(44) Gildersome remained part of the Bramley Union until 1925 when further reorganisation resulted in its affiliation with the Dewsbury Union, where it remained until the workhouse system was dismantled in 1930. Following its absorption into the Bramley Union, Gildersome’s workhouse found itself surplus to requirements. The barn and stables building was demolished to make way for the Methodist chapel around 1880. The principal building was converted into cottages around the same time. These cottages were still occupied in 1939 (part of Clayton Fold) and probably demolished sometime during the 1940s.

NOTES:

1] Dickens, C. (1838) Oliver Twist. Oxford: University Press, p.10.

2] Leeds Times, April 21, 1838.

3] Higginbotham, P. The Workhouse: the Story of an Institution. (online)

4] Driver, F. (1993) Power and Pauperism: The Workhouse System, 1834-1884, Cambridge: University Press, p. 148.

5] Newman, C.J. The Place of the Pauper: A Historical Archeology of West Yorkshire Workhouses 1834-1930. Unpublished Thesis.

6] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34. Booth was born in 1851. Given that the poorhouse was abandoned circa 1870, his assertion should be reliable.

7] WYAS, Registry of Deeds.

8] Kidd, A. (1999) State, Society and the Poor in Nineteenth-Century England, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, p.20.

9] Driver, F. (1993) Power and Pauperism: The Workhouse System, 1834-1884, Cambridge: University Press, p. 23.

10] Murray, P. (1999) Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914. London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 32.

11] Kidd, A. (1999) State, Society and the Poor in Nineteenth-Century England, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, p.28.

12] Murray, P. (1999) Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914. London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 45.

13] Shave, S. The Welfare of the Vulnerable in the Late 18th and early 19th Centuries: Gilbert’s Act of 1782. (Online)

14] Crompton, F. (1997) Workhouse Children. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. P. 51.

15] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34.

16] Shave, S. The Welfare of the Vulnerable in the Late 18th and early 19th Centuries: Gilbert’s Act of 1782. (Online)

17] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 31.

18] Ibid. P. 32.

19] Arnold-Baker, C. (1989) Local Council Administration in English Parishes and Welsh Communities. London: Longcross Press.

20] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 32.

21] Shave, S. (2017) Pauper Policies: Poor law practice in England, 1780-1850. Manchester: University Press, p. 11.

22] Leeds Times, Sept 17, 1836.

23] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p. 166.

24] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34.

25] York Herald, March 20, 1838.

26] Leeds Times, April 21, 1838.

27] Gildersome’s select vestry was ousted in 1837 during an extended period of interdenominational and political infighting that has been covered elsewhere on this site.

28] Leeds Intelligencer, March 24, 1855.

29] Leeds Mercury, Nov 5, 1859.

30] Rochdale Observer, Nov 5, 1859.

31] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p.p. 71-2.

32] Working as a woolsorter came at a cost. Throughout the century the industry was plagued with what became known as woolsorters’ disease (La maladie de Bradford), which would later be confirmed as pulmonary anthrax. Perhaps this had prompted Shaw to make his career change.

33] White’s Directory, 1858.

34] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p. 135.

35] Ibid. p. 140. A deed registered in 1883 confirms that a school was still being conducted in one of the rooms of the former workhouse by William Wells. This suggests that an already established school had continued for a while after the closure of the workhouse.

36] Carlton Hill Collection, University of Leeds. The workhouse school was situated in the present Gilead House.

37] Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales Vol. 2.

38] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

39] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

40] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

41] Hurriers were employed to move corves (coal wagons) from the coalface to the shaft. In collieries working thick coal seams, ponies were used; in Gildersome’s narrow seams, children were better suited to navigate galleries that could be as little as twenty-four inches in height. At Smith’s colliery, Gildersome, a full corve weighed around three and a half hundredweight.

42] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing, p.28.

43] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

44] Leeds Mercury, June 22, 1869.

1] Dickens, C. (1838) Oliver Twist. Oxford: University Press, p.10.

2] Leeds Times, April 21, 1838.

3] Higginbotham, P. The Workhouse: the Story of an Institution. (online)

4] Driver, F. (1993) Power and Pauperism: The Workhouse System, 1834-1884, Cambridge: University Press, p. 148.

5] Newman, C.J. The Place of the Pauper: A Historical Archeology of West Yorkshire Workhouses 1834-1930. Unpublished Thesis.

6] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34. Booth was born in 1851. Given that the poorhouse was abandoned circa 1870, his assertion should be reliable.

7] WYAS, Registry of Deeds.

8] Kidd, A. (1999) State, Society and the Poor in Nineteenth-Century England, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, p.20.

9] Driver, F. (1993) Power and Pauperism: The Workhouse System, 1834-1884, Cambridge: University Press, p. 23.

10] Murray, P. (1999) Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914. London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 32.

11] Kidd, A. (1999) State, Society and the Poor in Nineteenth-Century England, Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, p.28.

12] Murray, P. (1999) Poverty and Welfare 1830-1914. London: Hodder and Stoughton, p. 45.

13] Shave, S. The Welfare of the Vulnerable in the Late 18th and early 19th Centuries: Gilbert’s Act of 1782. (Online)

14] Crompton, F. (1997) Workhouse Children. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. P. 51.

15] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34.

16] Shave, S. The Welfare of the Vulnerable in the Late 18th and early 19th Centuries: Gilbert’s Act of 1782. (Online)

17] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 31.

18] Ibid. P. 32.

19] Arnold-Baker, C. (1989) Local Council Administration in English Parishes and Welsh Communities. London: Longcross Press.

20] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 32.

21] Shave, S. (2017) Pauper Policies: Poor law practice in England, 1780-1850. Manchester: University Press, p. 11.

22] Leeds Times, Sept 17, 1836.

23] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p. 166.

24] Booth, P.H. (1920) History of Gildersome and the Booth Family. P. 34.

25] York Herald, March 20, 1838.

26] Leeds Times, April 21, 1838.

27] Gildersome’s select vestry was ousted in 1837 during an extended period of interdenominational and political infighting that has been covered elsewhere on this site.

28] Leeds Intelligencer, March 24, 1855.

29] Leeds Mercury, Nov 5, 1859.

30] Rochdale Observer, Nov 5, 1859.

31] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p.p. 71-2.

32] Working as a woolsorter came at a cost. Throughout the century the industry was plagued with what became known as woolsorters’ disease (La maladie de Bradford), which would later be confirmed as pulmonary anthrax. Perhaps this had prompted Shaw to make his career change.

33] White’s Directory, 1858.

34] Fowler, S. (2007) Workhouse: The People, the Places, the Life Behind Doors. Kew: National Archives, p. 135.

35] Ibid. p. 140. A deed registered in 1883 confirms that a school was still being conducted in one of the rooms of the former workhouse by William Wells. This suggests that an already established school had continued for a while after the closure of the workhouse.

36] Carlton Hill Collection, University of Leeds. The workhouse school was situated in the present Gilead House.

37] Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales Vol. 2.

38] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

39] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

40] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

41] Hurriers were employed to move corves (coal wagons) from the coalface to the shaft. In collieries working thick coal seams, ponies were used; in Gildersome’s narrow seams, children were better suited to navigate galleries that could be as little as twenty-four inches in height. At Smith’s colliery, Gildersome, a full corve weighed around three and a half hundredweight.

42] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing, p.28.

43] Winstanley, I. The Coal Mining History and Resource Centre. Picks Publishing.

44] Leeds Mercury, June 22, 1869.