Nevison and a Gildersome Connection? © Andrew Bedford 2019

The infamous highwayman, John Nevison (local colliery owner Eric Towler) makes his appearance at the Gildersome Pageant. The coach and costumes may belong to a later period (Nevison was hanged in 1684), but everyone seems to be having a good time. (1)

The Gildersome Pageant of 1934 was organised to raise funds for the Leeds General Infirmary Extension Scheme. The highlight of this extravaganza was the arrival of a stagecoach, specially borrowed for the occasion from the Bradford Sewage Committee (exactly why the Bradford Sewage Committee was in possession of a stagecoach is unfortunately beyond the scope of this article). What was undoubtedly a showstopper also involved the appearance of a local legend: John Nevison the highwayman. The question as to why a convicted criminal almost forgotten to history was chosen as the pageant’s centrepiece is considered below.

A week or so before the pageant took place, the Yorkshire Evening Post ran an article about the forthcoming event, outlining Nevison’s career and notoriety. The article also offered a tentative justification for the highwayman’s inclusion in the pageant. The reason, it appears, was obvious; according to the paper, Nevison had ‘paid court to a fair lady who lived at Gildersome.’ However, as tends to be the case with ‘fair ladies’ this tantalising woman of mystery appears to have had at least one other admirer: one Fletcher ‘who, jealous of his rival’s dashing gallantry, sought to encompass his downfall.’ We are told that Fletcher, as jealous rivals tend to do, set a trap for the highwayman. Jealousy, however, can often become a barrier to judgement and Nevison, endowed as he was with ‘dashing gallantry,’ escaped ‘leaving Fletcher shot through the heart.’ Obviously, an alibi was required, so Nevison set off for York, reaching it with such astonishing speed ‘that it was thought incredible he could have been in the Gildersome district when the crime was committed.’ In an attempt to substantiate the story, the YEP makes mention of a ‘stone near Howley Hall Golf Club, on the borders of Batley and Morley’ bearing the inscription ‘here Nevison killed Flecher, 1684.’ The YEP writer then plays his ace by reminding us that ‘Gildersome in former days was part of Batley.’ (2) So, it becomes clear that Nevison’s top of the bill appearance at the Gildersome Carnival arose from the highwayman’s close connections with Gildersome, or does it?

Disappointing as it may be, on closer inspection the Gildersome connection proves to be tenuous at best. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the “fair lady resident in Gildersome” only makes her appearance in one version of the Nevison legend – the version as it is presented in the YEP article. Other sources do make mention of a love interest, though it would be a poor sort of legend that didn’t involve at least one fair lady. Norrison Scatcherd (who rarely has anything positive to say about Gildersome) is adamant, though, that Nevison’s paramour was a married woman living at Dunningley, whose ‘offspring and descendants were long honoured in his name’. (3) Scatcherd neglects to mention any evidence he may have to support his claim. However, even if such evidence existed, we might need to bear in mind that naming children in honour of a local celebrity might not necessarily amount to an actual relationship. On the other hand, Dunningley would not be that great a distance from Gildersome if one were able to travel across country (perhaps on Black Bess) by way of Churwell. Certainly close enough for the more romantically inclined to be able to confuse the two. Sadly the fair lady, whether native to Gildersome or Dunningley, appears to be little more than a melodramatic plot device.

The killing of Fletcher, on the other hand, carries significantly more weight and is repeated in most accounts of Nevison’s adventures. Fletcher is sometimes characterised as a constable, or sometimes an alehouse keeper, though one should not rule out the other. Scatcherd tells us that Fletcher kept a tavern at Howley Hall. (4) A deposition made to the magistrates at York in 1675 by one George Skipwith claimed that the master of the Talbot public house at Newark was an accomplice of John Nevison, while other sources claim that Nevison and his gang were accustomed to taking shelter in taverns up and down the country. It may not be beyond reason to suggest, then, that Nevison (an habitual frequenter of taverns) and Fletcher were already acquainted at the time of the incident. Scatcherd also asserts that the motive for Fletcher’s ambush was a government reward; Nevison’s criminal career having, by that time, become a source of considerable embarrassment for the nation’s justice system. So, according to legend, Nevison is plied with drink, overpowered and locked in an upstairs room from which he manages to escape. In the struggle that ensues, Fletcher is killed. Scatcherd goes on to relate that most accounts claim that Fletcher was shot through the heart (a poetically apposite end for a love rival). However, according to the testimony of an old man called Thomas Robertshaw of Soothill, who claimed to have known Nevison, the weapon was a short dagger or bodkin.(5) Whichever, Fletcher was dead and Nevison was on the run.

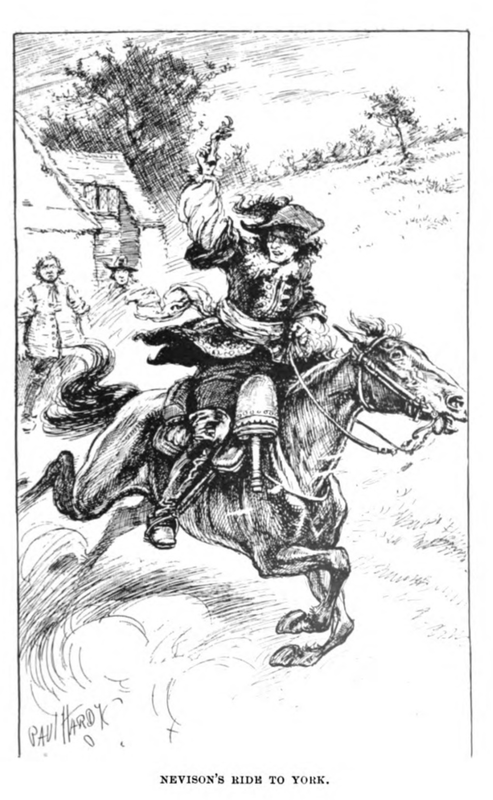

The clothing in this depiction (left), while perhaps a little theatrical, is at least contemporary with events. Whether the admiring bystanders are meant to be inhabitants of West Yorkshire or Kent depends on which version of the legend the reader prefers.

At this point, the legend really becomes confused. The ride from the scene of the murder to York at such a speed making it incredible that Nevison could have committed the deed has a number of variants. Many variations of the legend state that the journey to York had actually taken place earlier in Nevison’s career and that the starting point had been Gad’s Hill in Kent. It is from this version of events that Harrison Ainsworth wrongly attributed the ride to York to Dick Turpin in his novel “Rookwood.” Turpin subsequently became a household name, while Nevison was banished to relative obscurity. (6)

So, what evidence do we have for Nevison’s existence? Aside from local folklore, the answer is very little. In common with many other legendary figures, John Nevison proves to be a difficult character to pin down historically. (7) For example, while he is generally referred to as John Nevison, some accounts refer to William Nevison, or even Nevinson. It might be suggested that the latter can be accounted for by the local dialect in which Nevinson would have been pronounced Nevison, just as Stephenson was often corrupted to Stivison. Contemporary clerks and notaries unfamiliar with the local dialect are likely to have written the name as they heard it and hence the confusion.

The historical sources available tend to be sketchy. Many claim that he was born at Pontefract in 1639, though quite as many others assert that he was a native of Wortley near Sheffield. Of the two, the second hypothesis appears the more persuasive. In 1671 a case of Bastardy cited that ‘John Nevison younger of Wortley is charged to be the reputed father of a Bastard chyld by him begotten upon the body of one Anne Waynwright.’ (8) This documented evidence appears to confirm John Nevison as a native of Wortley. In 1675, George Skipwith attested that John Nevison was married and living near Pontefract. (9) Added to which, the parish register of Pontefract, St Giles and St Mary records the baptism of ‘John son of Mr John Nevison,’ and in 1708, Elizabeth, wife of John Nevison, was buried at All Saints, Wakefield. Taken altogether, this would suggest that Nevison had been born in Wortley and later set up house near Pontefract.

Scatcherd (and several others) refers to a ‘small stone of cylindrical shape bearing the inscription “here Nevison killed Flecher, 1684.”’ Scatcherd is unable to confirm exactly how long the stone has been in the grounds of Howley Hall, but states with some certainty that it was there as early as 1800. Scatcherd can even confirm that it had been engraved by ‘John Jackson, the schoolmaster of Lee Fair.’ Interestingly, however, a newspaper correspondent from 1881 claims that the date on the stone is wrong. This writer claims that the West Riding Session Rolls show that Edward Misden of North Empsall gave information on August the first 1681 before Sir Thomas Yarburgh to the effect that three strangers had told him that Davey Fletcher had been killed at Howley Park. This evidence is further supported by burial records from Batley Parish confirming that one Darcy Fletcher had been interred at Batley Churchyard on August the second 1681. Assuming that Darcy/Davey Fletcher is the same person, this evidence appears to carry some weight. It may be that with the passage of time between the murder and the engraving of the stone (possibly 100 years), the date of the murder had shifted to fit more closely with the date of Nevison’s capture and execution (a cogent example of the way in which legends can develop).

Most sources agree that Nevison was finally arrested at the Magpie Inn, Sandal (now the Three Houses) in 1684. (10) The date is substantiated by the records of Wakefield Sessions stating that the Constable of Sandal was ordered to pay 10s 6d to John Ramsden and William Hardcastle for conveying one Nevison, a highwayman, to the Castle of York. (11) An earlier record from Wakefield Sessions confirms that John Mowberry of Wentbridge had appeared at the sessions ‘for keeping company with John Nevison a highwayman.’ These documents provide compelling evidence that a highwayman named Nevison was indeed operating in the Wakefield area in the 1680s.

The crimes committed by Nevison are copiously documented in the legendary accounts and generally allude to daring stagecoach hold ups and gallant behaviour towards the fairer of his victims. However, were we to adopt a more objective perspective, it may be safer to adhere to the account provided in a deposition by one of his female associates. Elizabeth Burton, having been charged with stealing clothing at Mansfield, provided the magistrates with an account of the criminal activities perpetrated by Nevison and his associates. (12) It becomes clear from this account that Nevison’s victims were generally farmers and cattle drovers attending fairs and markets along the Great North Road. All the robberies described by Burton reveal that Nevison acted in concert with several others, which also questions the narrative of the lone highwayman inviting wealthy travellers to “stand and deliver.”

Most sources also agree that Nevison, following his arrest at Sandal, was taken to York and hanged at the Knavesmire in 1684. This is confirmed by a burial record from St Mary, Castlegate, York, stating that John Nevison was buried here on March 16, 1684. By the time of his death, Nevison had become something of a celebrity with the Yorkshire peasantry. His fame was such that ballads were sung about him in the local hostelries, including this extract that claimed to record his final speech on the scaffold:

A week or so before the pageant took place, the Yorkshire Evening Post ran an article about the forthcoming event, outlining Nevison’s career and notoriety. The article also offered a tentative justification for the highwayman’s inclusion in the pageant. The reason, it appears, was obvious; according to the paper, Nevison had ‘paid court to a fair lady who lived at Gildersome.’ However, as tends to be the case with ‘fair ladies’ this tantalising woman of mystery appears to have had at least one other admirer: one Fletcher ‘who, jealous of his rival’s dashing gallantry, sought to encompass his downfall.’ We are told that Fletcher, as jealous rivals tend to do, set a trap for the highwayman. Jealousy, however, can often become a barrier to judgement and Nevison, endowed as he was with ‘dashing gallantry,’ escaped ‘leaving Fletcher shot through the heart.’ Obviously, an alibi was required, so Nevison set off for York, reaching it with such astonishing speed ‘that it was thought incredible he could have been in the Gildersome district when the crime was committed.’ In an attempt to substantiate the story, the YEP makes mention of a ‘stone near Howley Hall Golf Club, on the borders of Batley and Morley’ bearing the inscription ‘here Nevison killed Flecher, 1684.’ The YEP writer then plays his ace by reminding us that ‘Gildersome in former days was part of Batley.’ (2) So, it becomes clear that Nevison’s top of the bill appearance at the Gildersome Carnival arose from the highwayman’s close connections with Gildersome, or does it?

Disappointing as it may be, on closer inspection the Gildersome connection proves to be tenuous at best. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the “fair lady resident in Gildersome” only makes her appearance in one version of the Nevison legend – the version as it is presented in the YEP article. Other sources do make mention of a love interest, though it would be a poor sort of legend that didn’t involve at least one fair lady. Norrison Scatcherd (who rarely has anything positive to say about Gildersome) is adamant, though, that Nevison’s paramour was a married woman living at Dunningley, whose ‘offspring and descendants were long honoured in his name’. (3) Scatcherd neglects to mention any evidence he may have to support his claim. However, even if such evidence existed, we might need to bear in mind that naming children in honour of a local celebrity might not necessarily amount to an actual relationship. On the other hand, Dunningley would not be that great a distance from Gildersome if one were able to travel across country (perhaps on Black Bess) by way of Churwell. Certainly close enough for the more romantically inclined to be able to confuse the two. Sadly the fair lady, whether native to Gildersome or Dunningley, appears to be little more than a melodramatic plot device.

The killing of Fletcher, on the other hand, carries significantly more weight and is repeated in most accounts of Nevison’s adventures. Fletcher is sometimes characterised as a constable, or sometimes an alehouse keeper, though one should not rule out the other. Scatcherd tells us that Fletcher kept a tavern at Howley Hall. (4) A deposition made to the magistrates at York in 1675 by one George Skipwith claimed that the master of the Talbot public house at Newark was an accomplice of John Nevison, while other sources claim that Nevison and his gang were accustomed to taking shelter in taverns up and down the country. It may not be beyond reason to suggest, then, that Nevison (an habitual frequenter of taverns) and Fletcher were already acquainted at the time of the incident. Scatcherd also asserts that the motive for Fletcher’s ambush was a government reward; Nevison’s criminal career having, by that time, become a source of considerable embarrassment for the nation’s justice system. So, according to legend, Nevison is plied with drink, overpowered and locked in an upstairs room from which he manages to escape. In the struggle that ensues, Fletcher is killed. Scatcherd goes on to relate that most accounts claim that Fletcher was shot through the heart (a poetically apposite end for a love rival). However, according to the testimony of an old man called Thomas Robertshaw of Soothill, who claimed to have known Nevison, the weapon was a short dagger or bodkin.(5) Whichever, Fletcher was dead and Nevison was on the run.

The clothing in this depiction (left), while perhaps a little theatrical, is at least contemporary with events. Whether the admiring bystanders are meant to be inhabitants of West Yorkshire or Kent depends on which version of the legend the reader prefers.

At this point, the legend really becomes confused. The ride from the scene of the murder to York at such a speed making it incredible that Nevison could have committed the deed has a number of variants. Many variations of the legend state that the journey to York had actually taken place earlier in Nevison’s career and that the starting point had been Gad’s Hill in Kent. It is from this version of events that Harrison Ainsworth wrongly attributed the ride to York to Dick Turpin in his novel “Rookwood.” Turpin subsequently became a household name, while Nevison was banished to relative obscurity. (6)

So, what evidence do we have for Nevison’s existence? Aside from local folklore, the answer is very little. In common with many other legendary figures, John Nevison proves to be a difficult character to pin down historically. (7) For example, while he is generally referred to as John Nevison, some accounts refer to William Nevison, or even Nevinson. It might be suggested that the latter can be accounted for by the local dialect in which Nevinson would have been pronounced Nevison, just as Stephenson was often corrupted to Stivison. Contemporary clerks and notaries unfamiliar with the local dialect are likely to have written the name as they heard it and hence the confusion.

The historical sources available tend to be sketchy. Many claim that he was born at Pontefract in 1639, though quite as many others assert that he was a native of Wortley near Sheffield. Of the two, the second hypothesis appears the more persuasive. In 1671 a case of Bastardy cited that ‘John Nevison younger of Wortley is charged to be the reputed father of a Bastard chyld by him begotten upon the body of one Anne Waynwright.’ (8) This documented evidence appears to confirm John Nevison as a native of Wortley. In 1675, George Skipwith attested that John Nevison was married and living near Pontefract. (9) Added to which, the parish register of Pontefract, St Giles and St Mary records the baptism of ‘John son of Mr John Nevison,’ and in 1708, Elizabeth, wife of John Nevison, was buried at All Saints, Wakefield. Taken altogether, this would suggest that Nevison had been born in Wortley and later set up house near Pontefract.

Scatcherd (and several others) refers to a ‘small stone of cylindrical shape bearing the inscription “here Nevison killed Flecher, 1684.”’ Scatcherd is unable to confirm exactly how long the stone has been in the grounds of Howley Hall, but states with some certainty that it was there as early as 1800. Scatcherd can even confirm that it had been engraved by ‘John Jackson, the schoolmaster of Lee Fair.’ Interestingly, however, a newspaper correspondent from 1881 claims that the date on the stone is wrong. This writer claims that the West Riding Session Rolls show that Edward Misden of North Empsall gave information on August the first 1681 before Sir Thomas Yarburgh to the effect that three strangers had told him that Davey Fletcher had been killed at Howley Park. This evidence is further supported by burial records from Batley Parish confirming that one Darcy Fletcher had been interred at Batley Churchyard on August the second 1681. Assuming that Darcy/Davey Fletcher is the same person, this evidence appears to carry some weight. It may be that with the passage of time between the murder and the engraving of the stone (possibly 100 years), the date of the murder had shifted to fit more closely with the date of Nevison’s capture and execution (a cogent example of the way in which legends can develop).

Most sources agree that Nevison was finally arrested at the Magpie Inn, Sandal (now the Three Houses) in 1684. (10) The date is substantiated by the records of Wakefield Sessions stating that the Constable of Sandal was ordered to pay 10s 6d to John Ramsden and William Hardcastle for conveying one Nevison, a highwayman, to the Castle of York. (11) An earlier record from Wakefield Sessions confirms that John Mowberry of Wentbridge had appeared at the sessions ‘for keeping company with John Nevison a highwayman.’ These documents provide compelling evidence that a highwayman named Nevison was indeed operating in the Wakefield area in the 1680s.

The crimes committed by Nevison are copiously documented in the legendary accounts and generally allude to daring stagecoach hold ups and gallant behaviour towards the fairer of his victims. However, were we to adopt a more objective perspective, it may be safer to adhere to the account provided in a deposition by one of his female associates. Elizabeth Burton, having been charged with stealing clothing at Mansfield, provided the magistrates with an account of the criminal activities perpetrated by Nevison and his associates. (12) It becomes clear from this account that Nevison’s victims were generally farmers and cattle drovers attending fairs and markets along the Great North Road. All the robberies described by Burton reveal that Nevison acted in concert with several others, which also questions the narrative of the lone highwayman inviting wealthy travellers to “stand and deliver.”

Most sources also agree that Nevison, following his arrest at Sandal, was taken to York and hanged at the Knavesmire in 1684. This is confirmed by a burial record from St Mary, Castlegate, York, stating that John Nevison was buried here on March 16, 1684. By the time of his death, Nevison had become something of a celebrity with the Yorkshire peasantry. His fame was such that ballads were sung about him in the local hostelries, including this extract that claimed to record his final speech on the scaffold:

But my peace I have made with my maker,

And now I’m quite ready to go;

So here’s adieu! To this world and its vanities,

For I’m ready to suffer the law (13)

I think it safe to say that the above doggerel is unlikely to have been uttered by Nevison, though it does illustrate the nature of legend construction. Whoever had written these not so immortal lines did so in order to sell them to a public for whom a momentary escape from drudgery would have been attractive enough to justify the cost of a printed broadside.

It seems fair to say that in spite of what amounts to reliable evidence for the actual existence of John Nevison the criminal, the legend of Nevison the highwayman continues to have far greater currency than that afforded by the evidence. Along with other legendary figures, the interest has been significantly enhanced by over three hundred years of story telling. What had in all probability been little more than a career in cattle stealing and blackmail (14) on the Great North Road came to be exaggerated to that of the gallant highwayman with an eye for the ladies. This perhaps illustrates another connection between Nevison and Turpin: both were basically horse thieves whose notoriety as “highwaymen” was largely developed by broadside sellers and taproom yarn spinners.

James Burnley concludes his essay on Nevison (15) with the following:

It seems fair to say that in spite of what amounts to reliable evidence for the actual existence of John Nevison the criminal, the legend of Nevison the highwayman continues to have far greater currency than that afforded by the evidence. Along with other legendary figures, the interest has been significantly enhanced by over three hundred years of story telling. What had in all probability been little more than a career in cattle stealing and blackmail (14) on the Great North Road came to be exaggerated to that of the gallant highwayman with an eye for the ladies. This perhaps illustrates another connection between Nevison and Turpin: both were basically horse thieves whose notoriety as “highwaymen” was largely developed by broadside sellers and taproom yarn spinners.

James Burnley concludes his essay on Nevison (15) with the following:

‘the terror with which he was regarded during the period he held such sway on the northern highways is amply testified by the fact that his name has been preserved as a byword for all that is wicked and reckless in the quiet country places of Yorkshire for two hundred years.’

I can personally verify this. My own interest in John Nevison was stirred by early memories of my grandmother referring contemptuously to anyone throwing their weight around as “Nevison.” It may be, then, that the local notoriety of the famous “highwayman” had provided the justification for Nevison’s appearance at the Gildersome pageant. However, as far as any tangible connection with Gildersome is concerned, the closest we are able to place Nevison with anything approaching certainty is Howley Hall, which, as the YEP pointed out, was close to Batley, and Gildersome was, at that time, in the parish of Batley.

On the other hand, were we to be persuaded by the idea that Nevison was born in South Yorkshire, another tenuous connection with Gildersome steps out of the shadows. According to one story, Nevison’s father was a steward at Wortley Hall at the same time as a man called Skelton. Skelton is alleged to have been the quarter master of a private troop of soldiers which was raised to quench the Farnley Wood Plot and assisted in the taking of Oates and Greathead. So, while Nevison may not have had any tangible connection to Gildersome, he may have once lived in the same house as a man that might have arrested an historical character with definite connections to Gildersome.

On the other hand, were we to be persuaded by the idea that Nevison was born in South Yorkshire, another tenuous connection with Gildersome steps out of the shadows. According to one story, Nevison’s father was a steward at Wortley Hall at the same time as a man called Skelton. Skelton is alleged to have been the quarter master of a private troop of soldiers which was raised to quench the Farnley Wood Plot and assisted in the taking of Oates and Greathead. So, while Nevison may not have had any tangible connection to Gildersome, he may have once lived in the same house as a man that might have arrested an historical character with definite connections to Gildersome.

Notes & Sources:

1) Leeds Mercury 1934. This publicity picture appeared a few days before the pageant was staged.

2) Yorkshire Evening Post, 1934.

3) Scatcherd, N. (1874) The History of Morley. Morley: S Stead, printer by steam power.

4) Scatcherd also makes the claim that nearby Scotsman Lane was named to mark the fact that a Scotsman had been murdered in the vicinity and thus might have been named in honour of Fletcher. Scatcherd’s “evidence” being that Fletcher “sounds Scottish.”

5) Scatcherd, N. (1874) The History of Morley. Morley: S Stead, printer by steam power.

6) It has been suggested that Robert Louis Stephenson projected a novel featuring the exploits of John Nevison though this was never completed. Had it been, the enduring legacies of Nevison and Turpin might have been very different.

7) The fact of his making an appearance in Macaulay’s History of England suggests that at least some of the legend is grounded in fact.

8) Wakefield Quarter Sessions, 1671.

9) Depositions from the Castle of York, volume 40.

10) There is a suggestion that the original Three Houses in which Nevison was taken may have been at the opposite side of Barnsley Road at the corner of Cock and Bottle Lane.

11) Burnley J (1885) Yorkshire Stories Retold, Leeds: Richard Jackson.

12) Depositions from the Castle of York, volume 40.

13) Sheffield Weekly Telegraph.April, 1912.

14) Blackmail, in its original meaning, is more akin to modern day extortion or protection money. Demanding money from drovers for safe passage would be more expedient than stealing their cattle and finding a buyer.

15) Burnley J (1885) Yorkshire Stories Retold, Leeds: Richard Jackson.

1) Leeds Mercury 1934. This publicity picture appeared a few days before the pageant was staged.

2) Yorkshire Evening Post, 1934.

3) Scatcherd, N. (1874) The History of Morley. Morley: S Stead, printer by steam power.

4) Scatcherd also makes the claim that nearby Scotsman Lane was named to mark the fact that a Scotsman had been murdered in the vicinity and thus might have been named in honour of Fletcher. Scatcherd’s “evidence” being that Fletcher “sounds Scottish.”

5) Scatcherd, N. (1874) The History of Morley. Morley: S Stead, printer by steam power.

6) It has been suggested that Robert Louis Stephenson projected a novel featuring the exploits of John Nevison though this was never completed. Had it been, the enduring legacies of Nevison and Turpin might have been very different.

7) The fact of his making an appearance in Macaulay’s History of England suggests that at least some of the legend is grounded in fact.

8) Wakefield Quarter Sessions, 1671.

9) Depositions from the Castle of York, volume 40.

10) There is a suggestion that the original Three Houses in which Nevison was taken may have been at the opposite side of Barnsley Road at the corner of Cock and Bottle Lane.

11) Burnley J (1885) Yorkshire Stories Retold, Leeds: Richard Jackson.

12) Depositions from the Castle of York, volume 40.

13) Sheffield Weekly Telegraph.April, 1912.

14) Blackmail, in its original meaning, is more akin to modern day extortion or protection money. Demanding money from drovers for safe passage would be more expedient than stealing their cattle and finding a buyer.

15) Burnley J (1885) Yorkshire Stories Retold, Leeds: Richard Jackson.