|

⬆︎ Use pull down menus above to navigate the site.

|

|

Joshua Greatheed of Gildersome © Charles Soderlund 12/23

|

It seems odd that Joshua Greatheed has remained unstudied for so long since he was at the centre of perhaps the biggest events in Gildersome and Morley's modern history. But then again, the Farnley Wood Plot and the 1663 risings in Yorkshire have been treated as mere footnotes by academics and by local historians as well. Greatheed can also be looked upon as the patriarch of the Scatcherd family, whose wealth and property became their legacy and brought about their creation as one of Morley's premier families. The following is an attempt to rectify that oversight...

The following is a list of contents, choose one or bypass the list and start reading. |

Introduction

Now followeth the Charracter of Joshua Greathead of Gildersom who was called Major Greathead he was reported to be a cunning knaveish man it was a very dangerous thing to be in his company, he was hated by all good men, yea of his neighbours who all stood in awe of him, he was employed sometime to collect Hearth money but behaved himself very ill and was cast out afterwards he was cast into prison, by his Letigacy at the suite of Richard Lepton of Gildersome for Three hundred pounds & died in the Kings Bench at London (1)

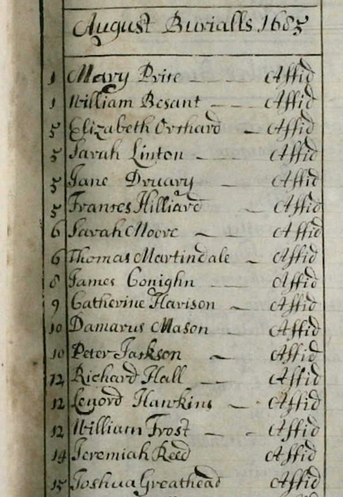

The above quote was probably written soon after Joshua Greatheed's death in 1685. The excerpt was from a document found at Wakefield in the office of the Manor Court, contained within a packet of miscellaneous deeds. It was penned in a seventeenth century style by someone unknown, who was familiar enough with Greatheed to have knowledge of the lawsuit between him and Richard Lepton. This event wouldn't have been widely discussed at the time. The rest of the document contained details of the executions of the so called traitors who participated in the Northern Rising of 1663 and the Farnley Wood Plot. (2)

|

Above: the only likeness of Joshua Greathead known to be in existence. From a Scatcherd collection on display at Morley's Town Hall.

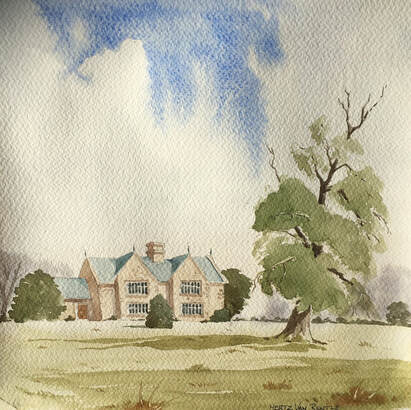

Above, Joshua Greatheed's house, we'll call Major's Hall, in Gildersome on today's Church St.

It was pulled down around the turn of the twentieth century, |

Joshua Greatheed (1615-1685) was born in Morley, at Morley Hole, and moved to Gildersome sometime in the 1640s. In my opinion he was Gildersome's most famous resident and still retains that status today. On the other hand, as the above quote suggests, he was probably Gildersome's greatest scoundrel. I hope to demonstrate this as the biography progresses. During the turbulent Civil War, he served in the Parliamentary Army under Thomas Fairfax and was promoted to Major for competence and bravery. His role in uncovering the "Great Northern Rebellion" of 1663 and especially the Farnley Wood Plot gained him notoriety, not just in Yorkshire, but within the halls of government, all the way up to King Charles the Second. However, to his Yorkshire comrades-in-arms and fellow Presbyterians he was vilified as the traitor responsible for the execution and imprisonment of many West Yorkshire men. After the Plot, he applied to the King, and was granted, a position as collector of the Hearth Tax in Yorkshire. His first assignment, 1666, as collector, failed when he came up over £2000 short. Thus began a series of investigations and charges that plagued him throughout the remainder of his life. During these hearings he consistently pleaded his innocence and blamed others while claiming his inability to reimburse the Exchequer. In response, the Crown seized many of his properties. Despite his obligation to repay the Crown, which he never did, he continued to wheel and deal, buying and selling properties, especially those rich in coal, and borrowed money which was hardly ever repaid, consequently engendering numerous lawsuits. It was one of these lawsuits (1684), filed by a close neighbour in Gildersome, which eventually brought Greatheed down. He was incarcerated in Fleet Street's debtors prison in London where, after a few months, he died.

|

|

Before proceeding I'd like to clear up a few misconceptions that have become part of his legend.

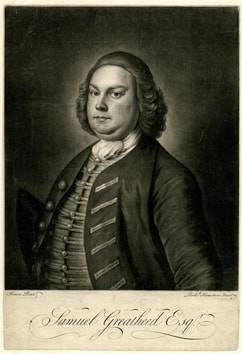

First, the portrait (right) which has been widely circulated showing the sitter with a tricorne under his right arm is not Joshua Greatheed but rather his great grandson Samuel Greatheed born 1710 on St Christopher's Island in the Caribbean.This mezzotint resides today at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Below is the Gallery's own citation: Sitter: Samuel Greatheed by Richard Houston, after William Hoare mezzotint, mid 18th century 12 1/2 in. x 8 3/4 in. (316 mm x 222 mm) Purchased with help from the Friends of the National Libraries and the Pilgrim Trust, 1966 Reference Collection NPG D2487 William Hoare (1707-1792), Portrait painter. Artist associated with 74 portraits, Sitter in 6 portraits. |

|

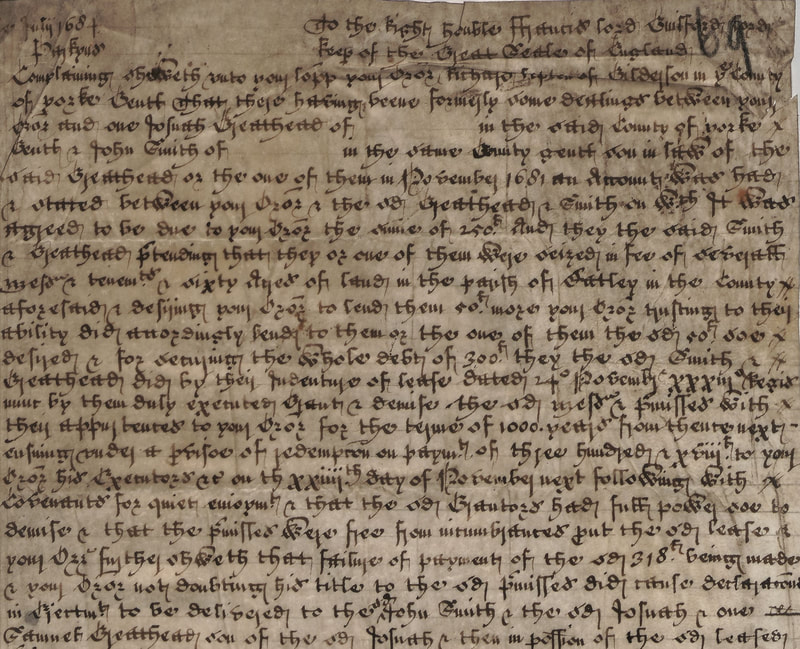

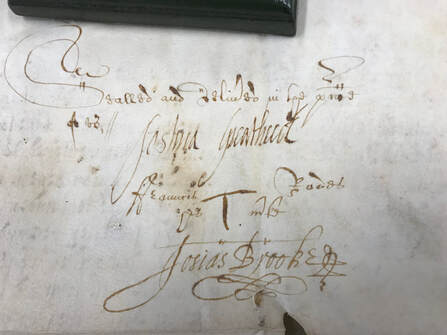

Second, that Joshua Greatheed, when signing deeds and other documents, used the spelling "Greatheed." I've seen his signature on many documents from the National Archives (Kew) and the West Yorkshire Archives Services (WYAS). Left, is an example from a 1670s deed signed by Joshua Greatheed as witness to the signing, it reads: "Sealed and delivered in the presence of us, // Joshua Greatheed - Franncis Rodes, her T mark - Josias Brooke." (3) This same spelling accompanies a few archival documents as well as birth, marriage and death records pertaining to Joshua's ancestors and descendants; in most he has been misnamed. Norrison Scatcherd (1780 - 1853), who wrote the long winded, A History of Morley, was a direct descendant of Joshua Greatheed. Scatcherd mentioned his illustrious ancestor quite a few times; each time he did so, he used the spelling Greatheed. Only the descendants of Thomas Greatheed used the Greatheed spelling, making it a great research tool when tracing the family's line. Note: I may call Joshua Greatheed "the Major" instead or use Greathead as interchangeable with Greatheed, especially when quoting documents.

|

Third, legend has it that after the Farnley Wood Plot, the Major was so hated by his neighbours that he dared not show his face in Gildersome and Morley. However, after 1663, every official document I've come across describes him as being "of Gildersome."

The Early Greatheeds of Morley and Gildersome

The Greatheed family had a long occupation in Batley parish and Morley especially. In a 1379 Poll Tax list for Morley, one William Greathede was wealthy enough to be included (4). The Greatheed name, in its various forms, appears now and then in Batley parish records from the 1500s and 1600s, but gaps in those records make a connection to the ancestral line of Thomas Greatheed, the Major's father, impossible. Though many Greatheeds lived in Batley parish prior to the 17th century it's not known if any had lived in Gildersome. The earliest Greatheed connection with Gildersome comes from the second half of the 16th century when Sir John Saville, Gildersome's manorial lord, disposed of most of his property held in demesne in that same manor. Sometime in the 1570s or 1580s, one John Greathead, along with John Stubley, of Stubley, received from Saville a grant of land in Gildersome of unquantifiable size. John Greathead along with his wife Isobel resided at Scholecroft, Morley, which is known, today, as Hillcrest Farm off Scotchman's Lane. Out of that grant, in 1589, they resold to the freeholders of Gildersome, a portion of that property which included fourteen subdivided fields: four Harthill Closes, four Moor Closes, four West Moor Closes and two Carr Closes. Among the purchasers was one Henry Crowther, his son became the father-in-law of the Major (5). When the said John Greathead died in 1595, his last will and Testament left property in Pontefract to his grandson, Thomas Bury, and money for the "poore in Gildersome," as well as the poor in Morley, Churwell and Batley. He named Isabel, his wife, heir and executrix to the residue of his estate in which no properties were mentioned, but certainly must have included Scholecroft. Since he bequeathed money to the poor in Gildersome, it's a good guess that he owned some property there at the time of his death (6). Thus far, the earliest record placing a Greatheed definitively in Gildersome is the death record of John Greatheed the younger brother of the Major who died in 1647(7). Most likely he lived with his brother, Joshua and family at Carr Hall. This property may have been a portion that Isobel Greathead inherited and passed down for the family's use. The next Greatheed to occupy Gildersome, as found in the surviving records, was Joshua Greatheed, the Major himself.

The Greatheed family had a long occupation in Batley parish and Morley especially. In a 1379 Poll Tax list for Morley, one William Greathede was wealthy enough to be included (4). The Greatheed name, in its various forms, appears now and then in Batley parish records from the 1500s and 1600s, but gaps in those records make a connection to the ancestral line of Thomas Greatheed, the Major's father, impossible. Though many Greatheeds lived in Batley parish prior to the 17th century it's not known if any had lived in Gildersome. The earliest Greatheed connection with Gildersome comes from the second half of the 16th century when Sir John Saville, Gildersome's manorial lord, disposed of most of his property held in demesne in that same manor. Sometime in the 1570s or 1580s, one John Greathead, along with John Stubley, of Stubley, received from Saville a grant of land in Gildersome of unquantifiable size. John Greathead along with his wife Isobel resided at Scholecroft, Morley, which is known, today, as Hillcrest Farm off Scotchman's Lane. Out of that grant, in 1589, they resold to the freeholders of Gildersome, a portion of that property which included fourteen subdivided fields: four Harthill Closes, four Moor Closes, four West Moor Closes and two Carr Closes. Among the purchasers was one Henry Crowther, his son became the father-in-law of the Major (5). When the said John Greathead died in 1595, his last will and Testament left property in Pontefract to his grandson, Thomas Bury, and money for the "poore in Gildersome," as well as the poor in Morley, Churwell and Batley. He named Isabel, his wife, heir and executrix to the residue of his estate in which no properties were mentioned, but certainly must have included Scholecroft. Since he bequeathed money to the poor in Gildersome, it's a good guess that he owned some property there at the time of his death (6). Thus far, the earliest record placing a Greatheed definitively in Gildersome is the death record of John Greatheed the younger brother of the Major who died in 1647(7). Most likely he lived with his brother, Joshua and family at Carr Hall. This property may have been a portion that Isobel Greathead inherited and passed down for the family's use. The next Greatheed to occupy Gildersome, as found in the surviving records, was Joshua Greatheed, the Major himself.

|

The Major's Parents and Siblings

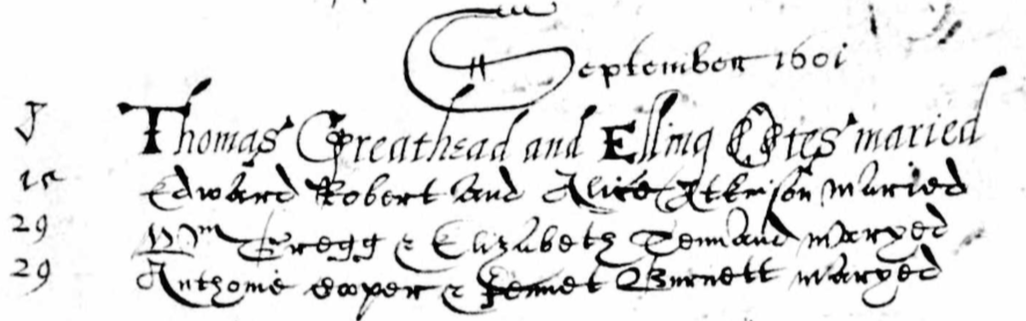

As mentioned previously, the Major's family tree begins with his parents,Thomas Greatheed (c1575-1622), and Ellen Greatheed nee Oates (c1579-16??), (see above). They were married in Leeds on the 8th of September 1601. Thomas was a clothier. Regarding their children, I can find only six boys born to the couple, they may have had other children but if they did, they remain unknown. Their boys were: (8)

The family owned an estate in Morley, which was centred at Morley Hole (read the Morley Hole study to the right). Prior to his death in 1622, Thomas sold half of his estate to the Trustees of the Batley Grammar School. Thomas, died and was buried on the 5th of February 1622 at Batley (10). The next year, 1623, Ellen, his wife and Peter, the eldest son, sold the remaining half. Peter immediately leased back a portion of their former property and perhaps lived for a time off the proceeds from the sale (11). What life was like for the Greathead children and their mother after Thomas' death, we can only imagine. If Thomas left a will then Peter, the eldest (19 yo), was probably named a co-executor and principle heir, while each of the other brothers, all below the age of 18, were undoubtedly left money or property or both, to be claimed upon their maturity.

The family appears not to have been lacking in resources. Peter became a clothier in Morley, following in his father's footsteps. After the Morley Hole sale, the family had enough money to secure brother Thomas, at the age of 17, a seat at Magdalen College, where he achieved a B.A. in 1627 (age 22) and matriculated from Magdalen Hall with an M.A. (12). In fact all the brothers received a good education, though where is not presently known. Brother Robert died young at age 27 (13). Brother Nicholas eventually removed from Morley to Holbeck and engaged in the woollen trade. In May of 1644 he was "commissioned as a troop captain in Lord Fairfax's regiment of horse, having raised and financed his officers and 60 troopers." (14) Brother Joshua was described in his marriage banns (1637) as a clothier, so he must have apprenticed somewhere, perhaps with one of his brothers, either Peter or Nicholas (15). Finally brother John, the youngest, may have resided in Morley but died in Gildersome. Thus far little is known about John, He may have married but there's no definite proof. In the Protestation Oaths (1641 to 42) administered in Batley Parish which included Morley and Gildersome, the list of oath takers recorded no male Greatheed or Greathead, 18 or over, as having taken the oath, though there were plenty of them. What's probable was that the Greatheeds practiced one of the various dissenting doctrines popular in Yorkshire at the time and either refused to take the oath or made themselves scarce when it was administered. During the Civil War, bothers Peter, Thomas, Nicholas and Joshua Greathead all joined the Parliamentary Army, were commissioned officers and served with distinction. In praise of Joshua Greatheed, Clements Markham, in his 'Life of Thomas Fairfax,' wrote the following:

the young warriors who flocked to the standard of SirThomas Fairfax, and displayed their prowess on Adwalton Moor. One of these was Joshua Greathead, then aged twenty-eight, who behaved with extraordinary gallantry. Wherever the work was hottest on that fateful day, there was young Greathead's sword gleaming in the sunlight; and, when at last he was forced down Warren's Lane in the press of fugitives, he took away with him more than one honourable wound. His hat, pierced with two bullets, and with the brim literally cut into shreds by cavalry swords, was long preserved by his family. About the 7th of July 1643, one week after the Battle of Adwalton, Joshua and his brother Nicholas, presumably with their families, appeared at a double baptism at St. Peters in Leeds. Joshua was recorded in the church book as being "of Headrow" and was there to witness his son Joshua Junior's baptism. Nicholas was recorded as "of Morley" with a son called Samuel. What's of most interest though, is that Joshua must have been stationed in Headrow, Leeds, perhaps convalescing or manning the defences, or both. (16)

In 1643 Joshua was promoted major of horse. In 1648 the Major was paid £499 in arrears and £120 in expenses and was probably mustered out of the Regular Army at the same time (17). However, in 1650, he was commissioned as a major in the Yorkshire militia, a position he probably held until 1660, when many with republican leanings lost their government appointments. (18) Peter Greatheed of Morley township served as:

An army quartermaster, and later a sequestrator in Agbrigg and Morley wapentakes. (19) |

Vertical Divider

|

The case for Morley Hole

Did the Greatheed family reside in Morley Hole? In Norrison Scatcherd's book, "A History of Morley?" he mentions several seventeenth century houses there, including the one above in an early twentieth century photo. All those houses have since disappeared.

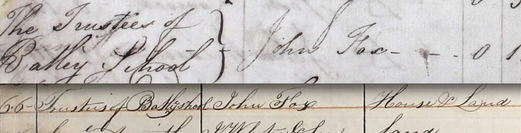

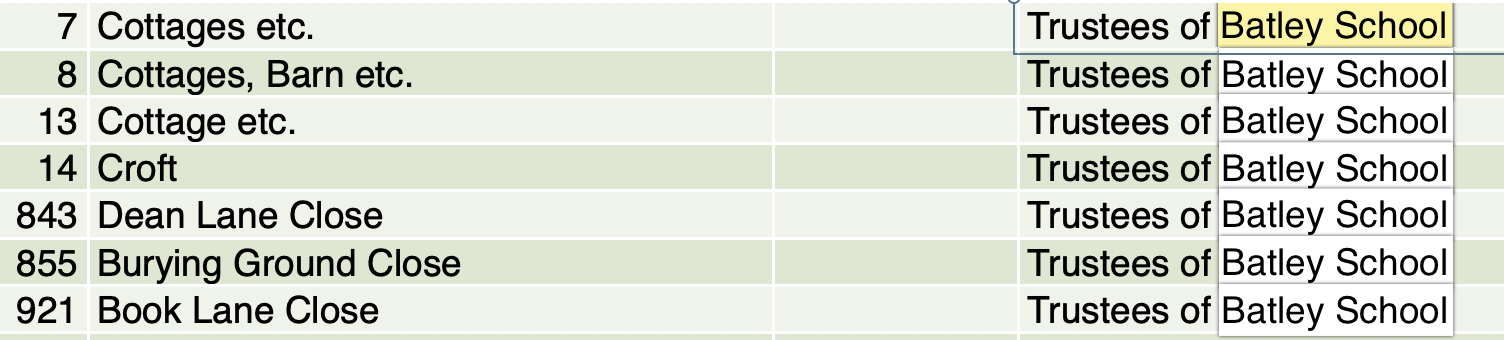

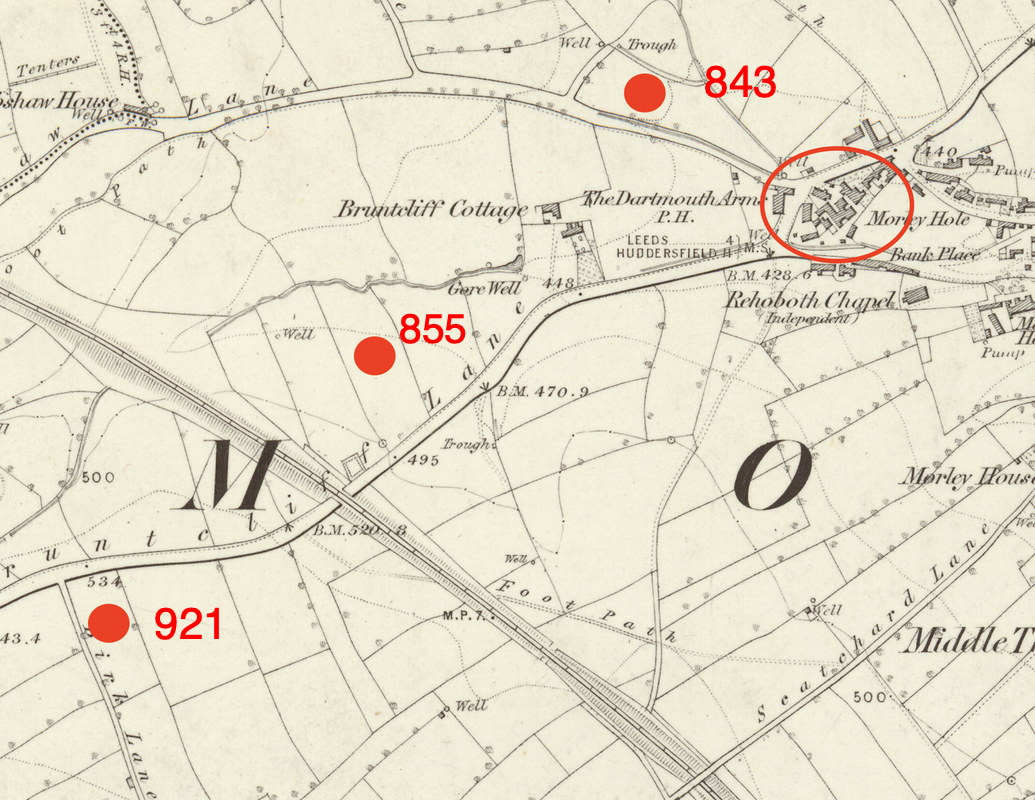

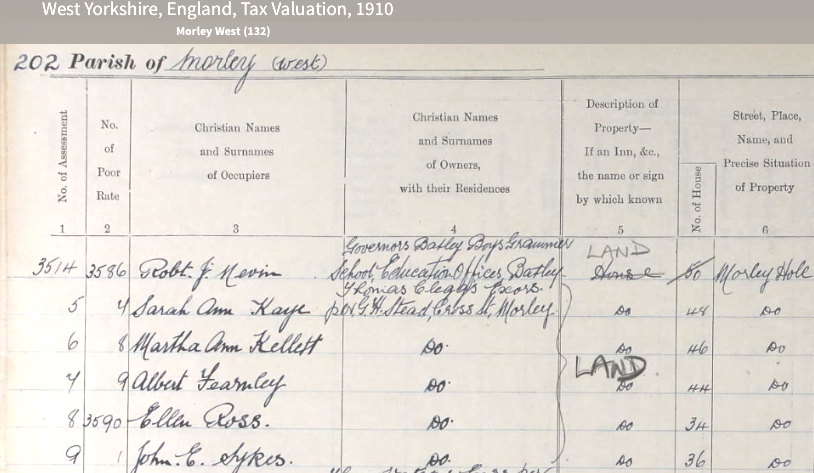

In Michael Sheard's book, Records of the Parish of Batley, pg. 171 (1894), he gives an account of the properties owned by the old Batley Grammar School whose rents were applied to the school's maintenance. One of the properties purchased by the school's trustees was in Morley and owned by Thomas and Ellen Greatheed, the parents of Joshua Greatheed. The sale was accomplished in two halves, the first in 1622 by Thomas to the Batley trustees. The second sale to the trustees, 1623, was by Ellen and her eldest son Peter, Thomas having died the previous year. The next year, 1624, the Trustees leased the same property to Peter Greatheed for 21 years. A description of the transferred property from the lease is as follows, "two messuages, barns, buildings, orchards, gardens, lands, closes, meadows, feedings, pasture, woods, underwood, &c, in anywise belonging." In 1636 the property was again leased to Peter for an additional 58 years. The terms of the lease were limited to Peter, his children and his grandchildren. Peter died in 1649, apparently without any progeny, and as Sheard further states: "In 1650, all entitled to any interest under this lease, must have died or surrendered it, for in that year the trustees granted a lease of the estate to Abraham Dawson." Sheard then includes a list, in chronological order, of the occupiers of the old Greathead estate, beginning with Dawson in 1659 and ending with John Fox in 1799. Below, excerpts from local records follow the trail of owners and occupiers up to 1910: Using the early 1700s Dartmouth Plan of Morley (www.morleystory.online/1716-plan.html) one can find a William Fox and a John Dawson occupying Morley Hole, a freehold. The Morley Tax Assessments (below) for the years 1781 and 1827 record John Fox as the occupier of the Batley School properties. (Click to Expand) Below, the 1843 Tithe Apportionments for Morley list all the properties still held by the school. No's. 7, 8, 13 and 14 are in Morley Hole.

In the 1843 map (below) that accompanies the Morley Tithe Apportionment's, Morley Hole dominates the centre. The four circled properties were still owned by the Batley Grammar School.

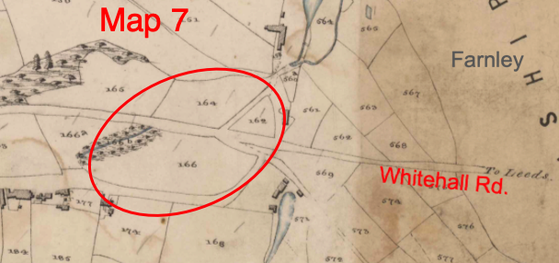

The portion of the 1850s OS map below, shows the location of the other three closes as described in the Tithe Apportionments. Given the wide distribution of the remaining school properties, one wonders whether the estate was originally larger and had been subdivided and sold. |

Nicholas Greatheed of Holbeck township served:

In May of 1644 Nicholas was commissioned as a troop captain in Lord Fairtax's regiment of horse, having raised and financed his officers and 60 troopers. He served at the siege of York and at the battle of Marston Moor. Greathead relinquished his commission on 2 Dec. 1645, his troop passing to Adam Baynes. In 1648 he claimed a £944 3s in arrears and £693 10s in expenses. (20)

Thomas Greatheed of Morley township served:

From 17 May 1643 to 1 Jan. 1644 Thomas was a Quartermaster in George Gill's regiment of horse. By 20 Jan. 1644 he had been promoted captain of a troop in John Lambert's regiment of horse. in which he fought at the battle of Nantwich. In Feb. 1644 he returned with Lambert to the west riding. Greathead served with the regiment into June 1645, and probably well after. In 1648 he claimed arrears of £985 13s and £566 in expenses. (21)

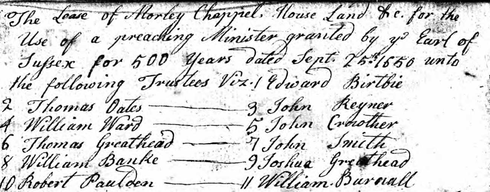

In 1650, during the Interregnum, a trust deed signed by Lord Thomas Savile of Howley Hall had been granted to lay impropriators (all dissenters) containing..... a parcell of land called the Chappell yeard wherein the Chappell at Morley now standeth. Among the eleven trustees who had signed the deed on behalf of the lay congregation were Thomas Greathead of Morley, his brother Joshua Greathead and John Smith both of Gildersome as well as Thomas Oates, of Morley, the Major's first cousin. Others signing the deed were: John Rayner, John Ellis, William Ward, John Crowther, Wm. Bancke, Robert Paulden, and William Burnell, all from the county of York. (22)

Peter Greatheed died in 1649. Having no direct heirs, the lease on his Morley Hole estate was terminated in 1650 and evidently not renewed. Whatever accumulated wealth he possessed must have passed on to his surviving brothers, Thomas, Joshua, and Nicholas. According to a deed made out in 1650, Nicholas was living in Holbeck, Thomas was living in Morley and Joshua was living in Gildersome having most likely removed there sometime in the 1640s.

At the beginning of the hostilities between the Royalists and Parliament, Nicholas apparently purchased a commission with Fairfax in the parliamentary army. He provided equipment, horses and sixty men. Whether this was done out of his own funds or from borrowing is yet to be discovered (23). In 1648, he asked Dame Mary Bolles of Heath Hall near Wakefield for the loan of £500. In return he signed a bond, putting up 50 acres of his property as security (24). This loan was probably made to tide him over until the nearly £1700 in arrears owed to him by Parliament was forthcoming. I have good reason to suspect that Nicholas, along with many other officers from the North, was never fully reimbursed by Parliament for their service. Instead of repaying the full amount to Dame Mary, he was forced to pay its interest each year. This continued until 1653 when he defaulted (25). Between 1652 and 1657, Nicholas appears to have been desperately in debt. As corroboration, in 1653 Nicolas was in the King's Bench Prison, presumably over the Dame Mary Bolles loan (26). In addition, residing in the National Archives at Kew are no less than eight other litigations involving Nicholas and money matters. In the Bolles v Greathead case (1654), the plaintiff's and defendant's statements are available but the court's ruling is missing (27), in spite of that, I'm certain the court ruled in favour of Dame Mary, resulting in the forfeiture of Nicholas' fifty acres plus an unknown quantity in penalties. This appears to have been a severe blow in the sad decline of a brave former parliamentary officer. In 1657 Nicholas Greatheed passed away and his brother Joshua Greatheed was appointed his estate's administrator (28), as presumably Nicholas died intestate. As Nicholas' administrator, the Major was sued by Mary Jackson of Leeds over £80 pounds supposedly owed to her deceased husband by Nicholas. Again, the decision in the case is missing, however, this illuminating sentence was found in the defendants testimony: ....Nicholas Greathead being likewise lately dead very poore and possessed of very small or noe personall estate. (29)

At the beginning of the hostilities between the Royalists and Parliament, Nicholas apparently purchased a commission with Fairfax in the parliamentary army. He provided equipment, horses and sixty men. Whether this was done out of his own funds or from borrowing is yet to be discovered (23). In 1648, he asked Dame Mary Bolles of Heath Hall near Wakefield for the loan of £500. In return he signed a bond, putting up 50 acres of his property as security (24). This loan was probably made to tide him over until the nearly £1700 in arrears owed to him by Parliament was forthcoming. I have good reason to suspect that Nicholas, along with many other officers from the North, was never fully reimbursed by Parliament for their service. Instead of repaying the full amount to Dame Mary, he was forced to pay its interest each year. This continued until 1653 when he defaulted (25). Between 1652 and 1657, Nicholas appears to have been desperately in debt. As corroboration, in 1653 Nicolas was in the King's Bench Prison, presumably over the Dame Mary Bolles loan (26). In addition, residing in the National Archives at Kew are no less than eight other litigations involving Nicholas and money matters. In the Bolles v Greathead case (1654), the plaintiff's and defendant's statements are available but the court's ruling is missing (27), in spite of that, I'm certain the court ruled in favour of Dame Mary, resulting in the forfeiture of Nicholas' fifty acres plus an unknown quantity in penalties. This appears to have been a severe blow in the sad decline of a brave former parliamentary officer. In 1657 Nicholas Greatheed passed away and his brother Joshua Greatheed was appointed his estate's administrator (28), as presumably Nicholas died intestate. As Nicholas' administrator, the Major was sued by Mary Jackson of Leeds over £80 pounds supposedly owed to her deceased husband by Nicholas. Again, the decision in the case is missing, however, this illuminating sentence was found in the defendants testimony: ....Nicholas Greathead being likewise lately dead very poore and possessed of very small or noe personall estate. (29)

Joshua Greatheed, his Wife and Children

Joshua Greathead married Susan Crowther (1620-1684) on the 28th of May 1640 (30), however they first announced their intention to wed in the marriage banns of 1637 (31). It would be interesting to find out the reason for the three year delay, perhaps it was negotiating a dowery. Whatever the reason, the couple were wed at the Batley parish church. Susannah's parents, Ralph Crowther (1585-1658) and Alice Crowther nee Scott (b 1580) were married on 15 Oct 1617 at Batley parish church (32). Ralph's father was Henry Crowther, mentioned in the 1580s Greatheed and Stubley sale above. In those days, the Crowthers were a large Gildersome and Morley clan whose trades included mining, smithing, tanning and cloth making.

Joshua and Susannah had the following children. Except for Hannah and Henry who were certainly born in Gildersome, it's not clear whether the others were born in Gildersome or Morley. However, with Joshua away with the parliamentary army, Susannah probably had her children at her parents house in Gildersome, then called Newhouse. (33)

Joshua Greathead married Susan Crowther (1620-1684) on the 28th of May 1640 (30), however they first announced their intention to wed in the marriage banns of 1637 (31). It would be interesting to find out the reason for the three year delay, perhaps it was negotiating a dowery. Whatever the reason, the couple were wed at the Batley parish church. Susannah's parents, Ralph Crowther (1585-1658) and Alice Crowther nee Scott (b 1580) were married on 15 Oct 1617 at Batley parish church (32). Ralph's father was Henry Crowther, mentioned in the 1580s Greatheed and Stubley sale above. In those days, the Crowthers were a large Gildersome and Morley clan whose trades included mining, smithing, tanning and cloth making.

Joshua and Susannah had the following children. Except for Hannah and Henry who were certainly born in Gildersome, it's not clear whether the others were born in Gildersome or Morley. However, with Joshua away with the parliamentary army, Susannah probably had her children at her parents house in Gildersome, then called Newhouse. (33)

- Alice - b. about 1640, d. 1727. She married John Smith of Gildersome abt. 1658, they had at least 5 children.

- Joshua - b. about July 1643, d. 1665. He died unwed.

- Samuel - b. about 1644, d. 1721. he married Susannah Appleyard of Gildersome June 1682. They appear to have had no children.

- Hannah - Hannah's birth and death remain uncertain. What's certain is that she was born before 1655 when all of her siblings, except Henry were mentioned in a 1655 conveyance by her grandfather, Ralph Crowther. She died unmarried. She has often been mistaken for Hannah Wood nee Smith (1669-1758), her niece who married Nehemiah Wood.

- John - b. about 1645, d. about Jan 1710 in London. He married Jane Hill in 1670 in London and the couple probably had one boy and two girls both called Anne. He then married Margaret Boote in London in 1689. They had no children.

- Susannah - b. about 1652, d. 1741 in Gildersome, unmarried.

- Henry - b. about 1658, d. 1718 in Gildersome. he married Martha Fox (nee Kinge) in London 1689, she was born 1651 in London and died in Morley 1722. They had at least one child, Mary born 1691, who married Samuel Scatcherd. (34)

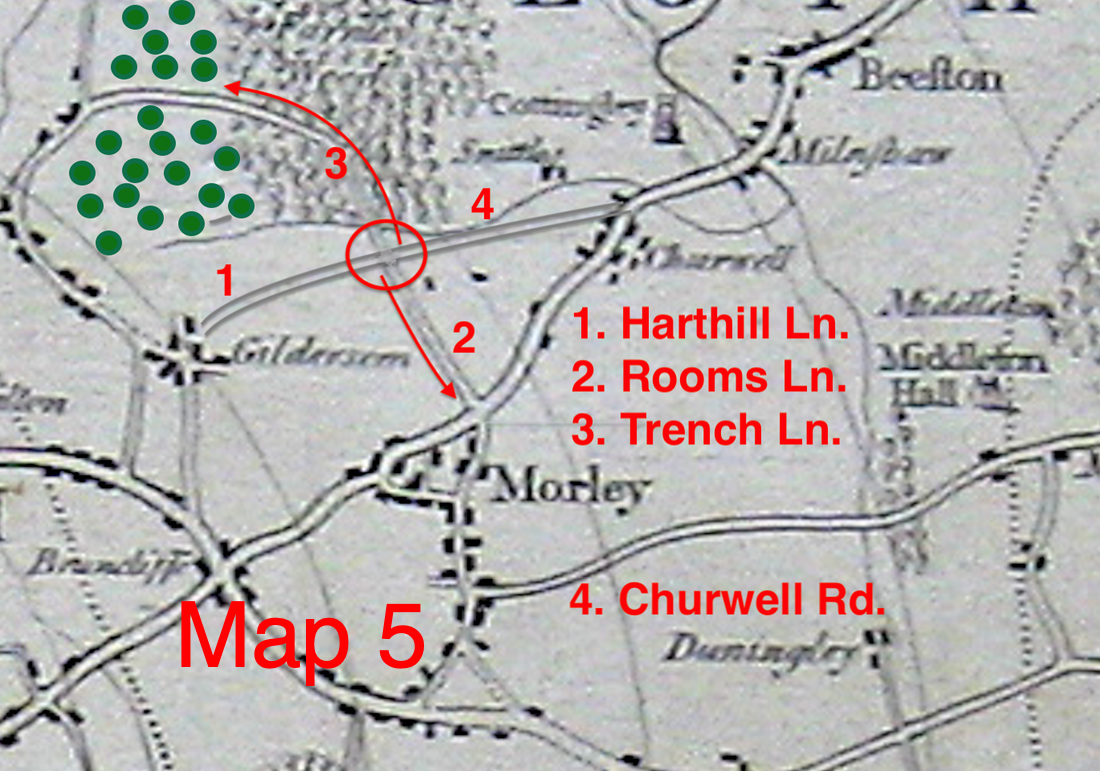

The Major's Gildersome

The earliest description of Gildersome came from Barnard’s survey of 1577 which reported that it was a "hamlet having about twenty dwellings, where it was easy to settle and encroach on the wastes? (35) Prior to that, a rich abundance of iron ore combined with an extensive supply of woodland supported a thriving iron mining and smelting economy. This eventually stripped the land of most of its trees (36) and left in its wake great swaths of tree stumps and superficial damage from scarring, pitting and spoiling. During the sixteenth century, where once there was common land, the enclosure laws had separated field from field, and tenants had to pay for the privilege to use them. It was then that Gildersome's principle landholders, at the top being the Saville family who held the Manor, began a sell off of large tracts of the manor's exhausted fields to local yeomen and tradesmen. A good example of such a transaction is the Greatheed and Stubley purchase previously discussed above (37). By 1711, a survey plan of southwest Farnley made for Lord Cardigan, its manorial lord, also included his lands in Gildersome. It revealed that he owned some waste in Gildersome, probably containing 10 to 20 cottages, and owned only about 10 to 15 acres of its enclosed fields occupied by one tenant, freeholders owning the remaining 98% of the township. Contrast that with adjacent Morley where, at the same time, freeholders owned approximately 10% to 15% of Morley's total acreage and Morley's Lord Dartmouth owned the rest (38).

By1600 coal had become a highly sought after commodity and since Gildersome was awash in it, coal mining eclipsed iron mining, the woollen industry and farming becoming its most profitable industry. Crude coal mines began to litter the land especially near or within the old iron workings, such as Harthill, the western edge of Dean Beck and in the southern parts of the township mainly just above and "beyond the Street" (39) (the Bradford Wakefield Road). Gildersome's location, near the crossroads of the Street and the Leeds to Huddersfield road meant that it had a large and ready market for its coal, all within the radius of ten miles.

Gradually the old stumps left behind by the charcoalers were pulled and much of the land was cleared and by the time the 1666 Hearth Tax count was taken, Gildersome had grown to forty six houses, each containing one hearth or more. Of course this did not include the poorer classes living on the waste and those living rough. The greatest concentration of buildings, which could be considered the centre of town, was located around and near the Manor House, on Harthill, with farmsteads and houses radiating from the centre, many along today's Church and Town Streets. With population growth, the town centre was gradually shifting to occupy the area around the Green and the old town centre would later become known as Town End. Aside from its atypical quantity of coal and iron, during the 1600s Gildersome was probably similar to most other small villages, having the usual collection of tradesmen including the following, all found within surviving documents from that period: yeomen farmer, clothier, glover, salter, shoe maker, tanner, blacksmith and roper. Due to its proximity to the burgeoning town of Leeds, it also attracted gentlemen who preferred the country life but had their business interests in town.

Greatheed 's original holdings in Gildersome:

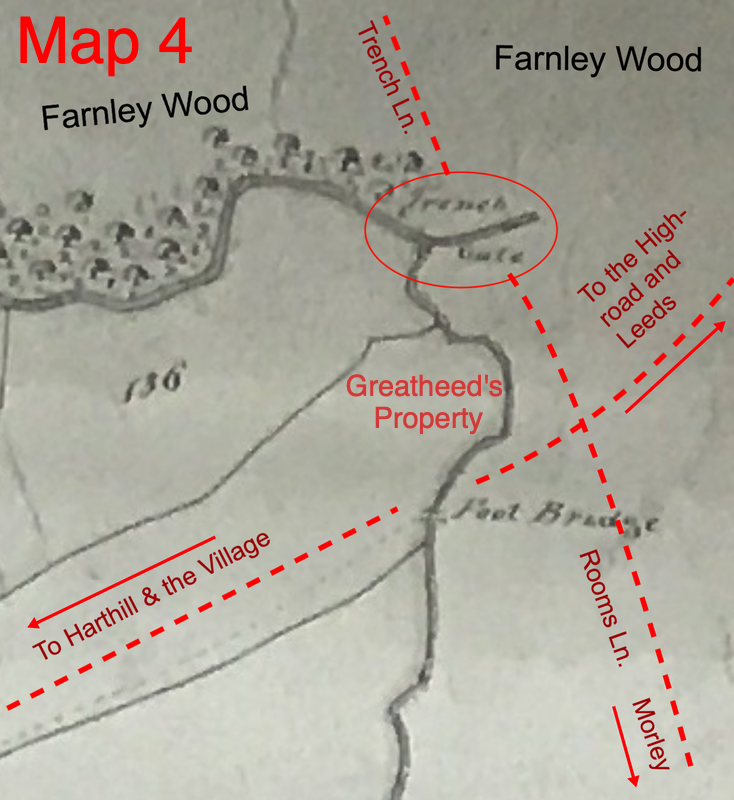

There still remains the question of whether the Greatheeds possessed ancestral land in Gildersome which could have been part of the 16th century Greatheed Stubley purchase. If not, it must have been acquired during the 1640s and could have been either purchased by a Greatheed or been part of a dowry from Ralph Crowther. The land in question was located in the northern half of Major's Farm, bordering on Farnley Wood and contained a farmstead located at present day Carr Hall. On Map 1 of Gildersome, below, the said property is located within the blue oval. Though the Major probably did reside there in the 1640s, he makes his first appearance in the surviving records in a deed dated1650 (40), which also happens to be the same year that he was promoted to Major in the Yorkshire militia. In that deed Greatheed leases to Richard Lepton, a yeoman and Gildersome neighbor, "a Lith close (land with a grain storehouse) called Hollings Close and the Sour Ing," (number 1 on Map 1, below). The Major, at that time, was clearly in a generous mood because the yearly rent was, "one red rose in the time of roses (if the sum be used) and no other or more rent provided." Though no rent was applied, Lepton was expected to maintain the appurtenances and manure the fields. The deed further states:

The earliest description of Gildersome came from Barnard’s survey of 1577 which reported that it was a "hamlet having about twenty dwellings, where it was easy to settle and encroach on the wastes? (35) Prior to that, a rich abundance of iron ore combined with an extensive supply of woodland supported a thriving iron mining and smelting economy. This eventually stripped the land of most of its trees (36) and left in its wake great swaths of tree stumps and superficial damage from scarring, pitting and spoiling. During the sixteenth century, where once there was common land, the enclosure laws had separated field from field, and tenants had to pay for the privilege to use them. It was then that Gildersome's principle landholders, at the top being the Saville family who held the Manor, began a sell off of large tracts of the manor's exhausted fields to local yeomen and tradesmen. A good example of such a transaction is the Greatheed and Stubley purchase previously discussed above (37). By 1711, a survey plan of southwest Farnley made for Lord Cardigan, its manorial lord, also included his lands in Gildersome. It revealed that he owned some waste in Gildersome, probably containing 10 to 20 cottages, and owned only about 10 to 15 acres of its enclosed fields occupied by one tenant, freeholders owning the remaining 98% of the township. Contrast that with adjacent Morley where, at the same time, freeholders owned approximately 10% to 15% of Morley's total acreage and Morley's Lord Dartmouth owned the rest (38).

By1600 coal had become a highly sought after commodity and since Gildersome was awash in it, coal mining eclipsed iron mining, the woollen industry and farming becoming its most profitable industry. Crude coal mines began to litter the land especially near or within the old iron workings, such as Harthill, the western edge of Dean Beck and in the southern parts of the township mainly just above and "beyond the Street" (39) (the Bradford Wakefield Road). Gildersome's location, near the crossroads of the Street and the Leeds to Huddersfield road meant that it had a large and ready market for its coal, all within the radius of ten miles.

Gradually the old stumps left behind by the charcoalers were pulled and much of the land was cleared and by the time the 1666 Hearth Tax count was taken, Gildersome had grown to forty six houses, each containing one hearth or more. Of course this did not include the poorer classes living on the waste and those living rough. The greatest concentration of buildings, which could be considered the centre of town, was located around and near the Manor House, on Harthill, with farmsteads and houses radiating from the centre, many along today's Church and Town Streets. With population growth, the town centre was gradually shifting to occupy the area around the Green and the old town centre would later become known as Town End. Aside from its atypical quantity of coal and iron, during the 1600s Gildersome was probably similar to most other small villages, having the usual collection of tradesmen including the following, all found within surviving documents from that period: yeomen farmer, clothier, glover, salter, shoe maker, tanner, blacksmith and roper. Due to its proximity to the burgeoning town of Leeds, it also attracted gentlemen who preferred the country life but had their business interests in town.

Greatheed 's original holdings in Gildersome:

There still remains the question of whether the Greatheeds possessed ancestral land in Gildersome which could have been part of the 16th century Greatheed Stubley purchase. If not, it must have been acquired during the 1640s and could have been either purchased by a Greatheed or been part of a dowry from Ralph Crowther. The land in question was located in the northern half of Major's Farm, bordering on Farnley Wood and contained a farmstead located at present day Carr Hall. On Map 1 of Gildersome, below, the said property is located within the blue oval. Though the Major probably did reside there in the 1640s, he makes his first appearance in the surviving records in a deed dated1650 (40), which also happens to be the same year that he was promoted to Major in the Yorkshire militia. In that deed Greatheed leases to Richard Lepton, a yeoman and Gildersome neighbor, "a Lith close (land with a grain storehouse) called Hollings Close and the Sour Ing," (number 1 on Map 1, below). The Major, at that time, was clearly in a generous mood because the yearly rent was, "one red rose in the time of roses (if the sum be used) and no other or more rent provided." Though no rent was applied, Lepton was expected to maintain the appurtenances and manure the fields. The deed further states:

"And also one sufficient way and passage for wayne carts and carriages and for no other uses, att all times of the year in on and through or in out and through the said South end of the same close of land called the SOUR in the access now there accustomed to and fro and between the said south end of the saide close and one layne called Stonygatelayne (a) which said south end of the said close and the said way and passage the said Joshua Greathead hath souled unto the said Richard Lepton....."(41)

(Click on map to expand)

(Click on map to expand)

Richard Lepton lived near the present day site of Manor Farm, off today's Spring View which back then was called Stoneygate Lane. The site may have been occupied for several hundreds of years prior to the 1650s when it became known as Lepton Place. The name endured until the turn of the 20th century .

(Map 1, below) Superimposed upon a modern map of Gildersome is a rough approximation of the Major's holdings between the years 1650 and 1686. It's helpful to remember that the map has been created using surviving documents and records, so some guesswork is inevitable. Many of the field names remained the same as they were found to be called in the 1843 Tithe Apportionments, but some of those fields may have been larger and had since been subdivided. The property within the blue oval was held by the Greatheeds prior to the 1650s. The rest of the properties, highlighted and bordered in yellow, came as either a marriage dowry or gift from Ralph Crowther to his daughter Susannah and her Greatheed grandchildren. The map also shows to whom the land passed after the Greatheed line in Gildersome had ended, i.e. the Smiths through Alice Smith nee Greatheed and the Scatcherds through Mary Greatheed, Henry's daughter, who married Samuel Scatcherd. Also noted are some of the other property owners and the general locations of their holdings.

Key to the Map:

The blue oval marks the earliest Greatheed land. The red star is the location of Major's Hall. The dashed yellow oval is the approximate area of the Queen's Tenement. The area within the red oval represents Lum Bottom and the Stone Pitts.

1. Lepton's Lease.

2. Major's Spring.

3. Carr Hall.

4. Jon Hole.

5. Bell Royds.

6. Layne side, Langleys, and Johnny Hole.

7. The Street, Bradford to Wakefield Road.

8. West and Birk Fields.

9. Later Andrew Hill Farm.

10. The Queen's Tenement .

11.Harthill, numerous owners and tenants.

12. Morley Hole, the Major's birthplace.

The area within the red oval represents Lumb Bottom and the Stone Pitts, fertile iron and coal beds.

(Map 1, below) Superimposed upon a modern map of Gildersome is a rough approximation of the Major's holdings between the years 1650 and 1686. It's helpful to remember that the map has been created using surviving documents and records, so some guesswork is inevitable. Many of the field names remained the same as they were found to be called in the 1843 Tithe Apportionments, but some of those fields may have been larger and had since been subdivided. The property within the blue oval was held by the Greatheeds prior to the 1650s. The rest of the properties, highlighted and bordered in yellow, came as either a marriage dowry or gift from Ralph Crowther to his daughter Susannah and her Greatheed grandchildren. The map also shows to whom the land passed after the Greatheed line in Gildersome had ended, i.e. the Smiths through Alice Smith nee Greatheed and the Scatcherds through Mary Greatheed, Henry's daughter, who married Samuel Scatcherd. Also noted are some of the other property owners and the general locations of their holdings.

Key to the Map:

The blue oval marks the earliest Greatheed land. The red star is the location of Major's Hall. The dashed yellow oval is the approximate area of the Queen's Tenement. The area within the red oval represents Lum Bottom and the Stone Pitts.

1. Lepton's Lease.

2. Major's Spring.

3. Carr Hall.

4. Jon Hole.

5. Bell Royds.

6. Layne side, Langleys, and Johnny Hole.

7. The Street, Bradford to Wakefield Road.

8. West and Birk Fields.

9. Later Andrew Hill Farm.

10. The Queen's Tenement .

11.Harthill, numerous owners and tenants.

12. Morley Hole, the Major's birthplace.

The area within the red oval represents Lumb Bottom and the Stone Pitts, fertile iron and coal beds.

The Crowther Legacy

In the 16th century, the southern portion of Major's Farm, down to Church Street and beyond (number 10 on Map 1, above) was part of what was known as the Queen's Tenement (42) to which a messuage and barn was included. The messuage was called the Queen's Cottage, which I believe was situated on or near to the future site of the Major's Hall (see: Map 1 below, the yellow oval). In 1597 the Queen's cottage was leased by Benjamin Crowther, but as the name suggests, the property belonged to the Crown. The proceeds from its rents were part of a Royal Endowment and were paid to support a Chantry Chapel in Middleton (43). The endowment probably ended shortly after 1603 with the death of Elizabeth the first. The property then came into the hands of Thomas Walker (44) who sold it to Thomas Wentworth and Henry Batt (45) who sold it to Henry Crowther, the grandfather of Susannah Greatheed nee Crowther.

In the mid to late 16th century, members of the Crowther family, among others, were delving near the surface of Gildersome for ironstone. This is verified by an account recorded circa 1567at the Farnley Smithies, an ironworks situated along Farnley Beck (46). By the mid 17th century the Crowthers occupied and mined a large amount of acreage in Gildersome containing easily obtainable coal beds (coal had become the more desirable commodity). While at work they also collected ironstone as a fringe benefit, since the two were often found together. The probable extent of the Gildersome property belonging to Ralph Crowther can be seen in the Map 1 above (with the exception within the blue oval, the remainder of those areas highlighted and bordered in yellow). In 1655, Ralph Crowther, in advance of his death, endowed most, if not all, of his Gildersome property to his daughter Susan Greatheed and her children (47). The introduction of that grant reads as follows:

In the 16th century, the southern portion of Major's Farm, down to Church Street and beyond (number 10 on Map 1, above) was part of what was known as the Queen's Tenement (42) to which a messuage and barn was included. The messuage was called the Queen's Cottage, which I believe was situated on or near to the future site of the Major's Hall (see: Map 1 below, the yellow oval). In 1597 the Queen's cottage was leased by Benjamin Crowther, but as the name suggests, the property belonged to the Crown. The proceeds from its rents were part of a Royal Endowment and were paid to support a Chantry Chapel in Middleton (43). The endowment probably ended shortly after 1603 with the death of Elizabeth the first. The property then came into the hands of Thomas Walker (44) who sold it to Thomas Wentworth and Henry Batt (45) who sold it to Henry Crowther, the grandfather of Susannah Greatheed nee Crowther.

In the mid to late 16th century, members of the Crowther family, among others, were delving near the surface of Gildersome for ironstone. This is verified by an account recorded circa 1567at the Farnley Smithies, an ironworks situated along Farnley Beck (46). By the mid 17th century the Crowthers occupied and mined a large amount of acreage in Gildersome containing easily obtainable coal beds (coal had become the more desirable commodity). While at work they also collected ironstone as a fringe benefit, since the two were often found together. The probable extent of the Gildersome property belonging to Ralph Crowther can be seen in the Map 1 above (with the exception within the blue oval, the remainder of those areas highlighted and bordered in yellow). In 1655, Ralph Crowther, in advance of his death, endowed most, if not all, of his Gildersome property to his daughter Susan Greatheed and her children (47). The introduction of that grant reads as follows:

TO ALL XPIAN (Christian) PEOPLE to whom this present writing Indented shall come: Raphe Crowther of Gildersome in the County of Yorke yeom sonne and heir of Henry Crowther late of the same deceased sendeth greeting in our lord on hailing: Know ye that the said Raphe Crowther for the fathers love and affection I have and beare towards Susan my daughter now wife of Joshua Greathead of Gildersome aforesaid in the said County Yorke and for the better maintenance and fray of living of her and her heirs after my decease and for the love and affection which I have and bear as well towards Alice Greathead, Hanna Greathead and Susan Greathead my grandchildren the three daughters of the said Joshua Greathead and for the augmentation of their persons AS towards Joshua Greathead, Samuel Greathead and John Greathead my grandchildren the three sonnes of the said Joshua Greathead (ed. son Henry had not yet been born) and for the better maintenance and advancement of them and their heirs and for divers other good causes and considerations..... (48)

Ralph then describes the following Gildersome properties which will transfer ownership upon his death. Fortunately, most of the field names survived into the mid 19th century and provide a reasonable estimate of their location.

....ALL THAT Messuage or Tennement called the Newhouse and all the house pasture barns buildings folds gardens orchards backsides and easements ...... now in the tenure or occupation of me the said Raphe Crowther AND ALSO one close or croft of land lying near or adjacent to the said messuage and also all the several closes of land herein after mentioned that is to say the Middlefield close the close called the close beyond the street the Westmoor close the little close called the little close by the laynside, the Moorfield close the close called John Hoyle the close called Bellroyd theretofore used in three closes and the close called Harthill. (49)

The grant specified that after Ralph's death all the aforementioned property was to come into the possession of the Major's wife and children when they came of age. The grant also included property in Drighlington and Morley. Grandson Henry was not included since he was born after Ralph died. Ralph Crowther died in 1658, and in his will is no mention of any landed property, indicating that he had disposed of most or all prior to his death. (50)

As mentioned previously, it's most likely that, when the Major removed to Gildersome, it was originally into Carr Hall with its associated land, mostly stretching west to Major Wood. The fields below that, down to Church Street, were owned by the Crowthers. It was they who built Newhouse which passed to the Greatheed grandchildren in 1658. Newhouse later became known as Major's Hall even though it passed to his wife and children. It was situated on Church Street across from today's St. Peters Church, and was near to or on the site of the old Queen's Cottage.

(Left) Major's Hall by Andrew Bedford.

At the time Newhouse was built and occupied, today's Church Street was nothing more than a country lane with few houses or farmsteads along its route. The lane ran from Morley in the east and to Farnley, Tong and Drighlington in the north and west. In 1666 the Hall was recorded as being occupied by the Major's eldest son, Joshua Jr. and in 1672, after Joshua Jr's death, the hall was occupied by his brother John. It was described as having five hearths. John Smith the Elder's house had six hearths and was once called by Norrison Scatcherd the grandest house in Gildersome, it occupied the site of the later Halstead House. Smith's son, also called John, married the Major's eldest daughter Alice, and they dwelt in a house with three hearths (possibly Carr Hall). (51)

(Left) Major's Hall by Andrew Bedford.

At the time Newhouse was built and occupied, today's Church Street was nothing more than a country lane with few houses or farmsteads along its route. The lane ran from Morley in the east and to Farnley, Tong and Drighlington in the north and west. In 1666 the Hall was recorded as being occupied by the Major's eldest son, Joshua Jr. and in 1672, after Joshua Jr's death, the hall was occupied by his brother John. It was described as having five hearths. John Smith the Elder's house had six hearths and was once called by Norrison Scatcherd the grandest house in Gildersome, it occupied the site of the later Halstead House. Smith's son, also called John, married the Major's eldest daughter Alice, and they dwelt in a house with three hearths (possibly Carr Hall). (51)

Numbers 8 and 9 on the big map above.

Numbers 8 and 9 on the big map above.

Greatheed and Crowther to Scott: In 1656, the Major and his father-in-law, Ralph Crowther, leased to William Scott the fields called (52) the Street Close, the West Field and Birk Close, part of which which would later come to be called Andrew Hill (53). How or why the Major and Crowther came to be partners in the lease is a mystery. The Scott family lived above Andrew Hill near the bend of Church Street and gave their name to today's Scott Green. The Andrew Hill property, especially at the low end, was rich in coal and iron ore and some of the old diggings can still be seen there today. In a 1738 deed Samuel Scatcherd the elder of Morley is named the property's owner, it "being his inheritance" (54), proving that the Greatheed family owned these properties after Ralph Crowther's death.

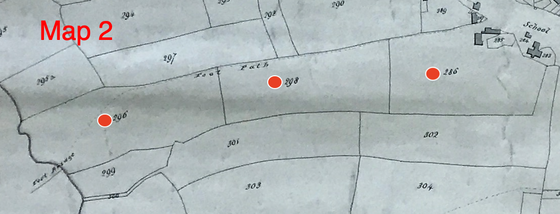

In the 1800 Enclosure Map of Gildersome (map 2 above) the three fields comprising the main properties of Andrew Hill are marked with red dots. In the 1843 Tithe Map, those same marked fields were called from left to right: Hillside or Brow, the Moor Field and the Overhouse Croft. The name Overhouse was derived from "oven house" that was once situated there in the 16th century, indicating a furnace and smelting activity.

In the 1800 Enclosure Map of Gildersome (map 2 above) the three fields comprising the main properties of Andrew Hill are marked with red dots. In the 1843 Tithe Map, those same marked fields were called from left to right: Hillside or Brow, the Moor Field and the Overhouse Croft. The name Overhouse was derived from "oven house" that was once situated there in the 16th century, indicating a furnace and smelting activity.

click on map to expand

click on map to expand

In 1681 an agreement made between the same Richard Lepton, mentioned above, and the Major with his son-in-law John Smith, involved the following properties which comprise what for centuries was known as the Major's Farm:

all that messuage or tenement and all the folds closes barns buildings, gardens orchards, outbuildings, folds easements and hereditaments whatsoever to the said messuage....also the following fields......SOUR ING GREAT ING the Upper Middle and nether BRACKENLEY The SPRING, Coats Close (of Herbert Royds) two closes called the CARR and the PIG HILL. (55)

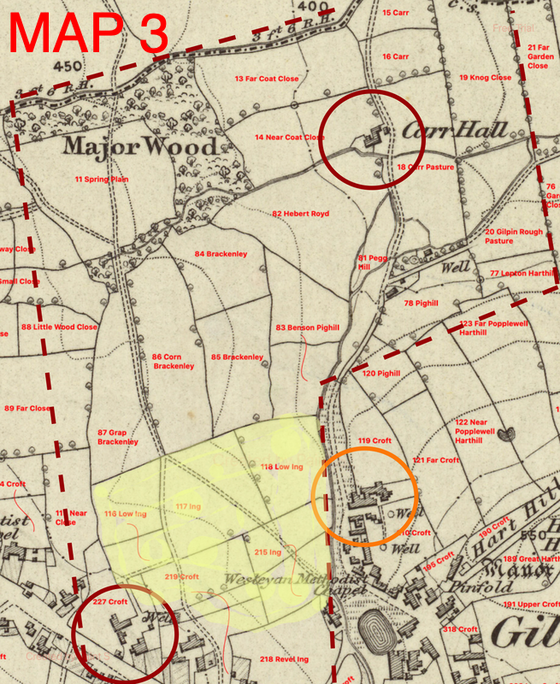

Map 3: Entered on to this portion of an 1850's O.S map of Gildersome, right, the field names from the Tithe map and Apportionments of the same period have been filled in by yours truly. Major's Farm is approximately delineated within the red dashed lines. If you click on the map, to see an enlarged version,you will find that the field names are exactly the same as they were in 1681, with the exception of the Great Ing which has been divided into smaller parcels, each called Ing (the yellow shading). Carr Hall, the above said messuage, is located in the upper red circle and the lower red circle is the Major's Hall. Lepton Place, still called that in the 1850s, is shown within the orange circle, and the lane running from there to Carr Hall was called Stoneygate Lane. The entire farm consisted of sixty acres more or less. It passed from the Greatheeds to the Scatcherds and remained in their possession until the beginning of the 20th century.

all that messuage or tenement and all the folds closes barns buildings, gardens orchards, outbuildings, folds easements and hereditaments whatsoever to the said messuage....also the following fields......SOUR ING GREAT ING the Upper Middle and nether BRACKENLEY The SPRING, Coats Close (of Herbert Royds) two closes called the CARR and the PIG HILL. (55)

Map 3: Entered on to this portion of an 1850's O.S map of Gildersome, right, the field names from the Tithe map and Apportionments of the same period have been filled in by yours truly. Major's Farm is approximately delineated within the red dashed lines. If you click on the map, to see an enlarged version,you will find that the field names are exactly the same as they were in 1681, with the exception of the Great Ing which has been divided into smaller parcels, each called Ing (the yellow shading). Carr Hall, the above said messuage, is located in the upper red circle and the lower red circle is the Major's Hall. Lepton Place, still called that in the 1850s, is shown within the orange circle, and the lane running from there to Carr Hall was called Stoneygate Lane. The entire farm consisted of sixty acres more or less. It passed from the Greatheeds to the Scatcherds and remained in their possession until the beginning of the 20th century.

Morley's Old Chapel Protest

On the 6th of April 1663, little over six months before the rising known locally as the Farnley Wood Plot, an armed protest occurred in Morley at the church containing the local Presbyterian chapel. It's now known as the 'Morley Old Chapel Protest.' On that day up to 200 protesters occupied the chapel by 'force of arms'. All the protesters seem to have been nonconformists of one bent or another and probably most were among the chapel's congregation. Shortly before the incident, the sitting minister, a dissenter, was compelled to 'conform' and swear an oath to the King as dictated in the newly enacted Act of Uniformity. This legislation forbade any form of religious service, ritual or ceremony, except as prescribed by the established episcopacy’s ‘Book of Common Prayer.’ The demonstrators' main concern was that the new regime was apparently forcing all of England into one church with one form of worship. To those who had enjoyed years of religious freedom under the Republic, this was an abomination. Twenty two men were soon identified as the prime conspirators and an arrest warrant was issued for their detention. Joshua Greatheed was included in the warrant as well as several other well known Gildersome men: John Smith, John Dickinson, Jeremy Boulton and William Scott. Of those five Gildersome men named, only William Scott was not on Sheriff Gower's payroll later in October. (56)

The incident is best described by the following verdict issued at the July Quarter Session at Leeds

against a certain Mr. Robert Halliday, one of 22 men singled out for arrest in a warrant in April:

On the 6th of April 1663, little over six months before the rising known locally as the Farnley Wood Plot, an armed protest occurred in Morley at the church containing the local Presbyterian chapel. It's now known as the 'Morley Old Chapel Protest.' On that day up to 200 protesters occupied the chapel by 'force of arms'. All the protesters seem to have been nonconformists of one bent or another and probably most were among the chapel's congregation. Shortly before the incident, the sitting minister, a dissenter, was compelled to 'conform' and swear an oath to the King as dictated in the newly enacted Act of Uniformity. This legislation forbade any form of religious service, ritual or ceremony, except as prescribed by the established episcopacy’s ‘Book of Common Prayer.’ The demonstrators' main concern was that the new regime was apparently forcing all of England into one church with one form of worship. To those who had enjoyed years of religious freedom under the Republic, this was an abomination. Twenty two men were soon identified as the prime conspirators and an arrest warrant was issued for their detention. Joshua Greatheed was included in the warrant as well as several other well known Gildersome men: John Smith, John Dickinson, Jeremy Boulton and William Scott. Of those five Gildersome men named, only William Scott was not on Sheriff Gower's payroll later in October. (56)

The incident is best described by the following verdict issued at the July Quarter Session at Leeds

against a certain Mr. Robert Halliday, one of 22 men singled out for arrest in a warrant in April:

Leeds the 16th day of July 1663

puts himself (before the jury), guilty

And that Robert Halliday, lately of Morley in the county of York, yeoman, with diverse other malefactors and disturbers of the peace of the Lord King, amounting to two hundred persons unknown to the aforesaid jury, on the fifth day of April in the fifteenth year of the reign of our Lord Charles the Second by the grace of God King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith etc., did by force of arms at Morley aforesaid, in the West Riding of the aforesaid county, riotously, tumultuously and illegally assemble and gather themselves for the disturbance of the peace of the said Lord King; and that the aforesaid Robert Halliday, together with the aforesaid other persons unknown to the aforesaid jury, being then and there assembled and then and there gathered, did with force of arms riotously, tumultuously and illegally then and there enter a certain chapel situated in Morley aforesaid in the West Riding in the county aforesaid called Morley Chappell, and then and there for the space of two hours on the same day remained in the aforesaid chapel, with force of arms, unlawfully, riotously and tumultuously and without any lawful authority, and then and there for the aforesaid time in the aforesaid chapel were engaged unlawfully, riotously and tumultuously, and made use of acts of religious worship and forms of prayer neither approved nor authorized or warranted to them by the laws of England, with the intention of disturbing the peace of the said Lord King, of putting fear into the government of the said Lord King, and of stirring up sedition in the nation and the subjects of the said Lord King, in contempt of the said Lord King, an evil example of all other offenders of this kind, and against the peace of the now said Lord King, his Crown and Dignity. (57)

I assume that those named in the original warrant were singled out as the main organisers, although their names may have found their way on to the list simply through witness identification. Rev. Thomas Smallwood, who was very well known, was probably the religious leader. He had been previously indicted at York for having demonstrated at Halifax and for saying this about Charles' Queen Catherine, a Catholic: “the whore of Babylon is rising and setting up.”(58) For that remark, he lost his seat as Vicar of Batley. The reputations of Joshua Greathead and Thomas Oates were well known in West Yorkshire and their presence must have added a great deal of credibility to the protest. Of the twenty two named in the warrant only eight faced trial. A Leeds court in July stated that, William Scott, Nathaniel Booth, Joseph Roades, Abraham Dawson & Thomas Atkinson all 'took the Oath of obedyense in open Corte.' I also found the same month that Thomas Smallwood, George Foster, Samuel Ward, Richard Halliday, Joseph Roades, Thomas Atkinson and Abraham Dawson each had a separate trial in which they were found guilty but were released on a promise to return the next session, until then they were to keep the King’s Peace (59). The remaining fourteen, about whom no court proceedings can be found, either remained at large or were brought to trial. All those who did have a hearing seem to have been dealt with very lightly, uncommonly so, given the severity of the charges. Is it possible that the sheriff and magistrates were purposefully light-handed at dispensing justice because their agents were among the Morley conspirators? I believe they were awaiting the maturation of the rebel's planned rising with the hope of catching all the guilty in one large treasonous net.

There's no record of Joshua Greatheed or his cousin Thomas Oates being brought up for charges. I believe that before and during the Chapel incident the Major was on the payroll for the Sheriff of York. Read on and make up your own mind!

There's no record of Joshua Greatheed or his cousin Thomas Oates being brought up for charges. I believe that before and during the Chapel incident the Major was on the payroll for the Sheriff of York. Read on and make up your own mind!

After the Farnley Wood Plot: the Hearth Tax:

Note: The Farnley Plot, its reasons and aftermath are too lengthy, complex and controversial for this article. Instead I intend to focus on Joshua Greatheed's betrayal and rewards. To read more about the Farnley Wood Plot and the Morley Old Chapel Protest, click on the references below:

Wikipedia The Farnley Wood Plot BBC Legacies The Old Chapel Morley Protest Greathead's Roll in the Plot Kirklees Cousins: Farnley Wood Plot

For the most academic account, read Andrew Hopper's:

The Farnley Wood Plot and the Memory of the Civil Wars in Yorkshire

Wikipedia The Farnley Wood Plot BBC Legacies The Old Chapel Morley Protest Greathead's Roll in the Plot Kirklees Cousins: Farnley Wood Plot

For the most academic account, read Andrew Hopper's:

The Farnley Wood Plot and the Memory of the Civil Wars in Yorkshire

Norrison Scatcherd (1780-1853), antiquarian and local historian, was a direct descendant of Joshua and Susannah Greatheed. He was born and raised in Morley, and owned property there. In Gildersome he owned most of the original seventeenth century Greatheed land, it having been passed on to the Scatcherds through Mary Scatcherd nee Greatheed, the Major's granddaughter. Norrison wrote 'The History of Morley' published in 1830 with a second edition published in 1874, about 19 years after his death. In it, he claimed to have many documents, original and copies, handed down from the 17th century. He wrote the following about the Farnley Wood Plot:

On the 12th of October,1663, 'says the memorandum of an ancestor of mine,' a little before midnight, the following conspirators did actually meet at a place called 'the Trench,' in Farnley Wood, viz: Captain Thomas Oates, Ralph Oates, his son, Joshua Cardmaker, alias Asquith, alias Sparling, Luke Lund, John Ellis, William Westerman, John Fossard (servant of Abraham Dawson, who lent him a horse), and William Tolson, all of Morley. John Nettleton and John Nettleton, jun., both of Dunningley, Joseph Crowther, Timothy Crowther, William Dickinson, Thomas Westerman,and Edward Webster, all of Gildersome. Robert Oldred, of Dewsbury, and Richard Oldred, commonly called the 'Devill of Dewsbury.' Israel Rhodes of Woodkirk, John Lacock of Bradford, Robert Scott of Alverthorpe, and John Holdsworth, of Churwell. Being all surprised at the smallness of their number, they made but a short stay, and, perceiving no more coming, Captain Oates desired them to return home, or shift themselves as they could.

In early 1664 in the town of York, twenty one men were condemned to death for treason. Nine of those men were from the Farnley Wood muster and were condemned primarily on the testimony of Major Joshua Greatheed (60). Yet ironically, the Major was one of their leaders and most, if not all, had joined because of his reputation. It was he who had persuaded them to rise, exaggerating the ranks of foot and horse ready to join the cause. Each man there at the "Trench" that night believed that civil war would erupt the very next day. But the Major wasn't there, where was he that night? He had been rounded up, three days earlier, in a preemptive sweep and incarcerated by the High Sheriff of York, as part of a group which included much of the plot's hierarchy throughout Yorkshire. Rumours concerning the Major's defection to the royalists' camp had been circulating and were quickly becoming widespread. Sir Thomas Gower, the High Sheriff, arrested the Major in an attempt to protect him, not only physically but with the futile hope of still preserving his cover. (61)

Two weeks before the Farnley meeting Gower wrote to civil servant Sir Joseph Williamson in London saying:

Two weeks before the Farnley meeting Gower wrote to civil servant Sir Joseph Williamson in London saying:

Gentlemen in the West Riding of Yorkshire have too hotly apprehended some of the ill-affected, on information of Major Greathead, who has an allowance from the Secretary for his discoveries, but now his information is publicly discoursed of, and the benefit of it will be less; he is one of many, and was close enough till he found some of his secrets known, and he is in danger of being made prisoner. (62)

A few days later Gower wrote the following to Secretary Bennet, the 1st Earl of Arlington, Keeper of the Privy Purse (Treasurer of the Royal Household) :

“The disaffected hold meetings, and profess to have a party in every county. Will use Greathead roughly,

because they begin to suspect him. (63)

“The disaffected hold meetings, and profess to have a party in every county. Will use Greathead roughly,

because they begin to suspect him. (63)

What happened? Why did this respected fighter for Presbyterianism and the Republic change sides, and aggressively so, betraying his friends, family, and comrades? Of course we'll never know his motives, probably the usual: the desire for money and power. To understand the depth of his collaboration with Sir Thomas Gower it's only necessary to see the rewards and the deference shown him by the King's own secretary. Even when he was actively defrauding the government, as shall be shown later, he was always treated lightly and with regard, as if he were the one man who saved the North from the rebellious plot.

The whole key to the Major's working relationship with Gower is the aforementioned allowance he received, which came right from the top, from the Treasurer of the Royal Household. Gower would never have brought such a dissenter and republican to the attention of the King's secretary unless he was absolutely certain the Major could deliver. Therefore Greatheed must have been subjected to a rigorous evaluation before gaining the sheriff's trust. Of course that would have taken some time and suggests that the Major, as Gower's agent, had attended conspiratorial meetings across the whole of the North during the early days of the plot's formation. At these meetings plans were freely discussed and no doubt the Major made suggestions and gave false counsel, all with the purpose of enlisting and ensnaring his unsuspecting comrades. How long he engaged in this strategy is unknown but as long as the plot grew and thrived, it meant job security. This is confirmed in a Nov 7, 1663 letter which Gower wrote to Sir Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, Secretary of State:

Sends up Major Greathead, with thanks for the assurance that his faithful service will be rewarded; he will

declare the whole design; he was thought so absolutely necessary to the military part that nothing could be

done without him, and was therefore fully trusted ..... (64)

The next day, the 8th, Gower again wrote to Secretary Bennet saying:

Major Greathead having been of great use, they gave him great hopes of reward, as well as indemnity; beg

that consideration may be had of him, in order that others may be encouraged to do the same. (65)

Enclosed in the above was a certificate, dated November 5th 1663, by Sir Thos. Gower and three other deputy lieutenants stating that:

Greathead has effectually contributed to the discovery of the late plot, and thereby to its prevention... (66)

In December 21st of 1663 in York, where the rebels treason trials were still ongoing, an order went out from the Lord Treasurer at Whitehall, granting Greatheed a position collecting hearth tax revenue out of which he could expect a percentage of the returns. As his 'farm,' he was given West Yorkshire and the city of York and his responsibility was to oversee the deputy collectors who would work the parishes. This office was a guaranteed income for life.

....to approve the petition of Joshua Greathead, for relief, and for a grant of the Collectorship of Excise

in Yorkshire, that as the petitioner did good service in discovery of the late plot, he shall have an

interest in the said collectorship when the present farm is expired. (67)

On the 23rd of December the relief mentioned above was sent in this instruction from the State Papers of Charles II, issued by Whitehall:

Warrant to pay Major Greathead £100 (approx. £10,500 today), as the King’s free gift, out of the £2000 for

secret services.

The whole key to the Major's working relationship with Gower is the aforementioned allowance he received, which came right from the top, from the Treasurer of the Royal Household. Gower would never have brought such a dissenter and republican to the attention of the King's secretary unless he was absolutely certain the Major could deliver. Therefore Greatheed must have been subjected to a rigorous evaluation before gaining the sheriff's trust. Of course that would have taken some time and suggests that the Major, as Gower's agent, had attended conspiratorial meetings across the whole of the North during the early days of the plot's formation. At these meetings plans were freely discussed and no doubt the Major made suggestions and gave false counsel, all with the purpose of enlisting and ensnaring his unsuspecting comrades. How long he engaged in this strategy is unknown but as long as the plot grew and thrived, it meant job security. This is confirmed in a Nov 7, 1663 letter which Gower wrote to Sir Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, Secretary of State:

Sends up Major Greathead, with thanks for the assurance that his faithful service will be rewarded; he will

declare the whole design; he was thought so absolutely necessary to the military part that nothing could be

done without him, and was therefore fully trusted ..... (64)

The next day, the 8th, Gower again wrote to Secretary Bennet saying:

Major Greathead having been of great use, they gave him great hopes of reward, as well as indemnity; beg

that consideration may be had of him, in order that others may be encouraged to do the same. (65)

Enclosed in the above was a certificate, dated November 5th 1663, by Sir Thos. Gower and three other deputy lieutenants stating that:

Greathead has effectually contributed to the discovery of the late plot, and thereby to its prevention... (66)

In December 21st of 1663 in York, where the rebels treason trials were still ongoing, an order went out from the Lord Treasurer at Whitehall, granting Greatheed a position collecting hearth tax revenue out of which he could expect a percentage of the returns. As his 'farm,' he was given West Yorkshire and the city of York and his responsibility was to oversee the deputy collectors who would work the parishes. This office was a guaranteed income for life.

....to approve the petition of Joshua Greathead, for relief, and for a grant of the Collectorship of Excise

in Yorkshire, that as the petitioner did good service in discovery of the late plot, he shall have an

interest in the said collectorship when the present farm is expired. (67)

On the 23rd of December the relief mentioned above was sent in this instruction from the State Papers of Charles II, issued by Whitehall:

Warrant to pay Major Greathead £100 (approx. £10,500 today), as the King’s free gift, out of the £2000 for

secret services.

Finally, as if the King's generosity toward this rustic yeoman from the North knew no bounds, on 15 May 1665 this interdepartmental memo was penned saying:

Reference to the Lord Treasurer on the petition of Major Greathead to be one of the Farmers of Excise

for Suffolk, the King wishing to gratify the petitioner, on account of his services in discovering the late

intended rebellion in the North. (69)

Greatheed began the collection of the hearth tax in Yorkshire in 1664. But by the beginning of 1666, those responsible for overseeing the tax collectors on the ground, called the Grand Farmers, discovered discrepancies in the Major's account. The assessments, mostly based upon several years of previous collections, did not tally with the actual returns. I'm not certain as to the initial alleged amount of the shortfall, but in one inquisition conducted in the town of York, the amount claimed had been reduced to £2400 (70). In March of 1666, the Major conducted his own investigation into the arrearage and compiled a lengthy report detailing the results which he submitted to the Grand Farmers who were unsatisfied with the Major's accounting (71). As a result, the next year he was ordered to cease collecting completely. During the years 1666 and 1668 a series of inquisitions were held in the city of York aimed at sorting out his shortage. In July 1667, the Major wrote to Lord Arlington, thanking him for a reference on his petition to the Treasury Commissioners. He asked why he must be a perpetual prisoner, and complained that "all his estate will not pay the money ordered by their lordships." (72) in 1668 the Farmer's auditor, presumably acting upon orders from above wrote: "The account to be engrossed with the allowances now made in consideration of Greathead's services."(73) After those allowances were applied to the Major's account, the debt owed was further reduced to about £1330 (at least 350,000 pounds in today's money). The only penalty imposed was the seizure of some of his unencumbered property. As near as I can tell this amounted to the sixty acres comprising Major's Farm in Gildersome as well as an unknown amount of property in Leeds, Morley and Drighlington.

Apparently, in 1666, Greatheed had joined in partnership with William Batt, Alexander Butterworth and Edward Copley, who were also hearth tax collectors (74). William Batt resided at Oakwell Hall, which was about a mile and a half from the Major's Hall in Gildersome. His son, also William Batt, was the famous ghost of Oakwell Hall having died in a duel in 1684. Alexander Butterworth, of Belfield near Rochdale, was apparently High Sheriff of Lancashire (1675 & 1676). Copley, who possessed Batley Manor and resided at Batley Hall, had entered into a bond with the King for the sum of £1350, as security for Joshua Greathead, the Receiver of the Hearth Tax (75). When the Major defaulted, Copley was called upon to honour the bond which he was financially unable to do. Copley's bond may have been the source of an equal reduction to the Major's balance owed. Copley had all his property seized and was ruined, to the great distress of his wife and children who inherited the debt after Copley's death in 1675. Fortunately, King James II., by deed dated 23 Mar., 1687, reconveyed the manor and lands to Edward Copley, his son and successor, and he entered and enjoyed the premises by virtue thereof. (76)

The sworn statement of Richard Lloyd Esq. (77), below, is the best example that reveals Batt, Butterworth and Greatheed's clear intention to brazenly defraud Lloyd, and indirectly through him the crown itself. I have little reason to doubt this assertion since it was a tactic the Major used numerous times. It also suggests that the trio, with Batt as its leader, purposefully conspired to misappropriate hearth tax money from the start.

Lloyd vs Batt, Butterworth and Greatheed: (78)