Iron Production in Medieval Gildersome by Charles Soderlund & Andrew Bedford © 03/2019

(It must be pointed out that this is not a geological study and that any diagrams or maps are approximations)

During the long period between the beginning of the Iron Age in Yorkshire and the coming of the Normans, the iron rich deposits found in the ridges and vales between the Aire and Calder rivers must have caught the eye of all foreign occupiers as they came in successive waves. Gildersome was one of those upland areas with abundant and easy to reach iron ore. It sat, as it still does today, near the convergence of two ancient roads. One of those routes ran from Bradford and Wakefield, right through the heart of this iron rich region. Whether the Romans built a road along its course is still a matter of debate, but it certainly must have been used by them as a secondary road. As for the other, it's well documented that the Romans did construct a series of highroads from York to Manchester whose route between Leeds and Birstall has been obliterated by urbanisation. Roman road experts place that missing piece of road somewhere near, or possibly passing through Gildersome.(1) There's no doubt that the Romans worked the valuable iron resources south of Leeds but there's no evidence of their presence in Gildersome. However, it goes without saying that, during the many historic eras prior to Domesday, there were periods of settlement in Gildersome, of varying degrees, that came and went and with them came crude ironworking. Unless some successful archaeological work is performed there, we'll never know much about who or how iron resources may have been exploited pre Conquest. What concerns us here is the post 1066 intensive ironworking that created the village of Gildersome.

William Smith, in his book c.1880, 'Morley Ancient and Modern', wrote the following about iron production in the region:

...... Cinderhill (in Morley), which derives its name from the numerous beds of cinders deposited here in former times. In the reign of the Plantagenets, and probably before then, there were many foundries in Morley and the neighbourhood. It is a striking fact connected with these foundries, that, though they were in many instances actually upon and but a few yards above beds of coal, the owners used timber more than anything else for their blast or smelting. One of these foundries was at the top of Neepshaw Lane, the place still being known as the "Stone Pits," thus bespeaking its origin, for the ore in this neighbourhood is still called "ironstone"; it is, therefore, probable that for brevity the old works or mines would be called the stone pits. That ironstone was meant is certain, for there was no stone suitable for building or road purposes in that locality. Scatcherd says: — "Before the woollen trade hereabouts became prevalent, the iron trade was carried on to a great extent nearly all around us. The Deightons, of Batley, were great ironfounders, and accumulated wealth."

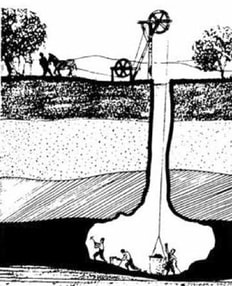

A Bell Pit Mine

A Bell Pit Mine

It is not beyond speculation that the discovery of ironstone nodules (iron ore) in the area known locally as Gildersome Bottoms, resulted in an Iron Age settlement. There, in an enclosure in the woods, a small group of people might have set up a crude furnace (called a bloomery) to smelt iron for their own domestic requirements, enabling them to make hammers, nails and axes. The readily attainable ironstone was probably mined in this way until the Normans eventually turned it into an organised enterprise. It's well known that ironworking took place in the West Riding during the Middle Ages. Archaeological evidence and post Conquest documents reveal a thriving industry in the area. As far as Gildersome is concerned, however, the earliest written evidence we have (c.1560s) confirms that ironstone was being mined in Gildersome for transportation to the nearby smithy at Farnley(2) and to the more distant furnaces of Shipley (3). It also appears that, as early as the 16th century, shifting markets and new technologies affected the demand for ironstone and Gildersome’s economy was already in a process of transition toward coal mining and cloth manufacture.

There is no hard evidence to suggest when ironworking began in Gildersome, or to what extent. However, the following discussion will attempt to demonstrate that, using a variety of available evidence, prior to the 16th century the manufacture of iron was taking place at Gildersome. It will also reveal the location of possible furnace sites, some of which might have been powered by watermills. Evidence will also be presented to show that the village of Gildersome probably developed around a site of early iron mining and processing, i.e. a smithy.

A smithy was a site where the process of extracting raw iron from ironstone took place. The finished product would be worked into the shape of an ingot called a bar (a smithy should not be confused with a blacksmith’s forge, at which bars purchased from the smithy would be converted into finished products). The primary resources necessary for a Medieval smithy’s operation were, ironstone, extensive woodland and a ready supply of water. Trees were felled and converted into charcoal, by charcoalers, to fuel the furnace and water was required to prepare the ore and later to power a bellows. The cost of transporting these materials rose proportionally as the distance increased, therefore it was advantageous, if not absolutely necessary, to have all these resources close at hand. During the early Middle Ages, Gildersome had these resources in abundance; it was also situated close to an ancient highway system that facilitated access to a wider market.

There is no hard evidence to suggest when ironworking began in Gildersome, or to what extent. However, the following discussion will attempt to demonstrate that, using a variety of available evidence, prior to the 16th century the manufacture of iron was taking place at Gildersome. It will also reveal the location of possible furnace sites, some of which might have been powered by watermills. Evidence will also be presented to show that the village of Gildersome probably developed around a site of early iron mining and processing, i.e. a smithy.

A smithy was a site where the process of extracting raw iron from ironstone took place. The finished product would be worked into the shape of an ingot called a bar (a smithy should not be confused with a blacksmith’s forge, at which bars purchased from the smithy would be converted into finished products). The primary resources necessary for a Medieval smithy’s operation were, ironstone, extensive woodland and a ready supply of water. Trees were felled and converted into charcoal, by charcoalers, to fuel the furnace and water was required to prepare the ore and later to power a bellows. The cost of transporting these materials rose proportionally as the distance increased, therefore it was advantageous, if not absolutely necessary, to have all these resources close at hand. During the early Middle Ages, Gildersome had these resources in abundance; it was also situated close to an ancient highway system that facilitated access to a wider market.

Records regarding the extent of Gildersome’s woodlands, from pre-Roman to the late Middle Ages are scarce. According to an archaeological sstudy, West Yorkshire was covered by an extensive forest when the Saxons first arrived, but by the time of the Domesday survey, some of this had been cleared for agriculture, especially in lower lying regions. The survey describes Gildersome as being situated between the zones of an “extensively wooded area” and a “partially wooded area”. (4)

The same survey reveals this:

The same survey reveals this:

"An award of c. 1233 describes Farnley Wood Beck as running 'between the wood of Farneley and the assart of Gildhus, suggesting that Gildersome township, like Longwood, developed from an assart. This would explain its omission from Domesday Book and the Nomina Villarum......Before its emergence as a township, Gildersome must have formed part of either Drighlington or Morley......." (5)

An assart, in its basic form, is a piece of land taken from the waste or forest, cleared of trees and made arable. It also could describe any small habitation that grew out of a wooded area. In Gildersome's case it could be interpreted that, 147 years post Domesday, the assart of Gildhus had developed as a clearing in the woodland. Was that development a direct result of mining activity? I believe so. Unfortunately, there is no mention of the date, size or location of that cleared land and no indication of the size of the preceding woodland. However, field and place names can provide clues as to which locations have been derived from woodland. Of the 352 fields reported in Gildersome’s 1843 tithe apportionments, over 25% retain a name pertaining to woods or woodlands. Examples of which are royd, shaw, birk, stubbs etc. Many more field names appear in deeds dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries that are woodland related, though these appear to have slipped out of use by 1843. Given the West Yorkshire Archaeological findings and the evidence of surviving field names, it is hard not to reach the conclusion that Gildersome in 1086 was predominantly woodland. However, over time the activities of the charcoalers had stripped Gildersome of its trees and changed the character of the landscape. Although foresters would have been employed to manage the dwindling resources, we can justifiably assume that by the mid 1500s local smelting was no longer profitable, as records show that Gildersome’s miners were exporting their ironstone to Farnley and elsewhere. (6)

Gildersome's Ironstone, known as Black Bed Ironstone, is located in a series of strata called the Lower Coal Measures in which the ore may lie above or below seams of coal. The ore is a black clay ironstone and its nodules are rich in iron with concentrations as high as 35 per cent. The thickness of the ore bed varies but never exceeds two feet (24 inches).(7) Another available source was the Tankersley Ironstone which overlays the Flockton Coal, better known locally as the Adwalton Black Bed. (8) In 1868, a peak year for iron production in Yorkshire, a combined total of 785,000 tons of iron, from these very same ironstones, was pulled from the ground in Morley, Batley and the Low Moor near Bradford.(9) It is also important to note that wherever ironstone is found, coal is close at hand. However, during the Middle Ages, coal was not as commercially viable as ironstone was and therefore probably ignored.

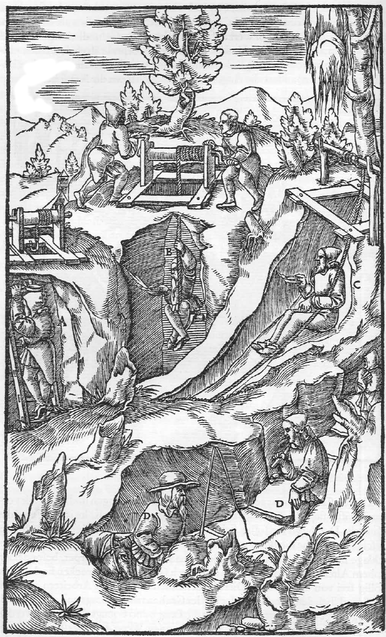

(In the depiction (above right), Medieval miners, called gravers, delve into a bank at ground level, one can also see ironstone nodules scattered about and a pot of boiling water used to make the stone friable in preparation for smelting. This scene is very similar to what one might have beheld near Gildersome Bottoms at Stoney Gate) (10)

(In the depiction (above right), Medieval miners, called gravers, delve into a bank at ground level, one can also see ironstone nodules scattered about and a pot of boiling water used to make the stone friable in preparation for smelting. This scene is very similar to what one might have beheld near Gildersome Bottoms at Stoney Gate) (10)

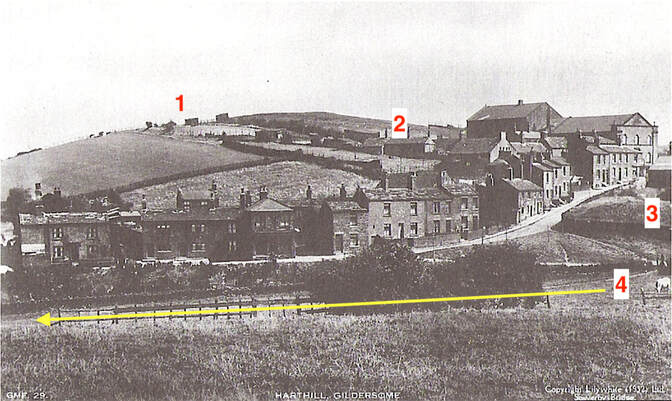

It's more than likely that the village of Gildersome grew out of a mining colony located at the intersection of the Leeds Road (called Harthill Lane), and The Bottoms. There, a seam of ironstone outcropped at "Black Bank," adjacent to the bottom of the Leeds Road, it then ran close to the surface, parallel to the road, for 300 yards in a northeasterly direction. (11) The same seam, displaced by a geological fault, ran out of The Bottoms in a northwesterly direction towards Moorhead and beyond.(12) For millennia, as the ironstone bearing bed eroded, its nodules of ore eventually found their way down into a beck in the area called Stony Gate, thus forming a concentrated deposit. With little effort, Gildersome's gravers (miners) were able to pluck the ore right from the stream bed. Given Gildersome's abundance of easily accessible iron ore and woodland, there's little doubt that a smithy was situated close to the centre of operations.( Stony Gate and Black Bank are names that have survived from that long ago era of iron mining.

(Above: A scene resembling the operations on Harthill: in the foreground, amid piles of extracted ironstone, gravers dig shallow pits as they follow a seam of ironstone, two men use rods to "divine" for rich deposits while two overseers look on. Meanwhile, in the background, the woodland is being denuded to feed the charcoaler's fire, seen in the upper left corner. (13)

(Above: A scene resembling the operations on Harthill: in the foreground, amid piles of extracted ironstone, gravers dig shallow pits as they follow a seam of ironstone, two men use rods to "divine" for rich deposits while two overseers look on. Meanwhile, in the background, the woodland is being denuded to feed the charcoaler's fire, seen in the upper left corner. (13)

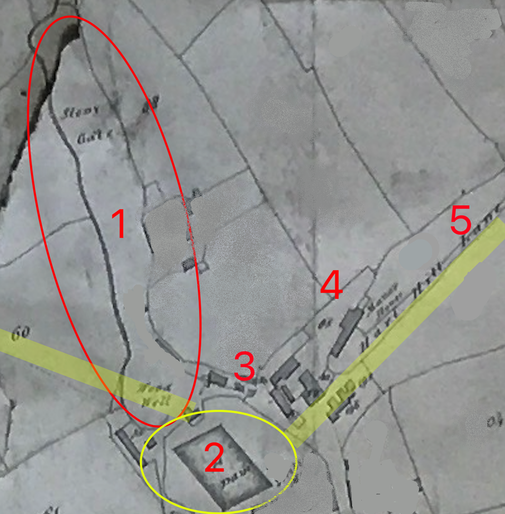

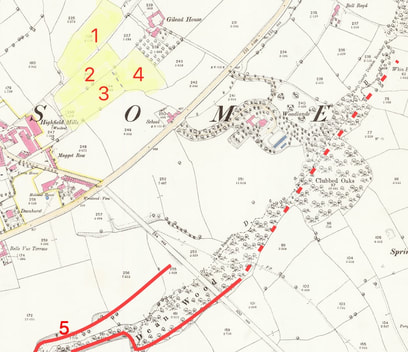

The clipping, below comes from the 1800 Enclosure Map of Gildersome and has been altered slightly (by me) to approximate how the hamlet of Gildersome might have looked during the Middle Ages. (Note: ignore the enclosed fields and try to imagine a woodland in their place). The two yellow stripes show the approximate location of the outcropping strata called the Black Bed, composed of ironstone nodules. (14)

|

1. Stony Gate (within the red oval): an aptly named area of waste containing a watercourse fed by many springs located in the higher ground to the south (in recent memory its been known as Blue Beck). For millennia ironstone nodules had washed out of the rich deposits on both sides of the stream's embankment, filling its channel with ore. In miner's terms this is called a "glory hole" or open quarry.

2. Pond or reservoir (within the yellow circle): created by constructing a dam, perhaps from mine tailings and slag. Over time, the ponds potential energy was used to power a succession of mills. 3. The Bottoms: the earliest site of the village of Gildersome. It makes sense that today's Town End was actually the end of town in Gildersome's early days. 4. The Manor House: it's no coincidence that a Reeve's house had been erected in this nexus of three rich ironstone deposits. (15) 5. The Leeds Road (Harthill Lane): again, it's no coincidence that the Leeds Road runs precisely parallel to the Black Bed Strata. |

In addition to the Black Bed deposits found at Harthill, another exploited deposit was the Tankersley Ironstone that overlays the Flockton Coal (better known locally as the Adwalton Black Bed). In Gildersome it's found south of Gelderd Road. On the east side of Dean Beck it's close to the surface and may outcrop along its east bank. I believe that the feature called Lumb Bottom was an artificial open quarry created by miners delving for ironstone directly into the embankment of Dean Beck. (16)

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

In the map, left, the solid red lines represents the location where the Tankersley Ironstone outcrops at the surface. Lumb Bottom is number 5. The red dashed line represents an approximate location of the outcropping Tankersley seam.(17)

The most telling support for medieval ironworking in Gildersome can be found in field names recorded in the 1843 Tithe Map and its associated Apportionments. The fields, highlighted in yellow in the map left, reveal the long ago presence of a smithy near Gilead House. Those numbered 1 thru 3 were called the Clay Crofts (clay was a necessary ingredient for construction of a bloomery). The field numbered 4 was called Cinderhill, in other words, large piles of slag.

The evidence indisputably leads to the conclusion that the Gilead House area was the site of a smithy. Furthermore, the presence of 'cinders' where there was inadequate water to power a mill suggests that it was a pre 16th century site.

The most telling support for medieval ironworking in Gildersome can be found in field names recorded in the 1843 Tithe Map and its associated Apportionments. The fields, highlighted in yellow in the map left, reveal the long ago presence of a smithy near Gilead House. Those numbered 1 thru 3 were called the Clay Crofts (clay was a necessary ingredient for construction of a bloomery). The field numbered 4 was called Cinderhill, in other words, large piles of slag.

The evidence indisputably leads to the conclusion that the Gilead House area was the site of a smithy. Furthermore, the presence of 'cinders' where there was inadequate water to power a mill suggests that it was a pre 16th century site.

|

(Left) This c.2003 aerial map depicts the same fields near Gilead House that appear in the map above. They are in much the same configuration as is shown in the 1843 Tithe Map. (Google Maps)

Note the pit mine like impressions littering the Little Clay Croft and the Top Close. Since the Middleton coal seam runs right through this area, it's almost a certainty that the pits were the result of later coal mining and not attributable to iron mining. (18) |

|

A third area of intensive mining took place in and around the fields called the Stone Pitts. For 800 years the Stone Pitts remained part of the demesne lands for the lords of Gildersome until it was sold in the 1880s. Unfortunately, today, it and Lumb Bottom have been covered by an industrial park. I believe that the "pitts" were mined later in Gildersome's history, perhaps the 1500s, and that coal was the primary objective and ironstone being a fringe benefit. It's documented that in the 1560s, the smithies at Farnley imported Gildersome stone from the Stone Pitts.(19) In addition, the smithies at Shipley received regular shipments from Gildersome, since Shipley's smithies were eight miles distant, transport could only have been cost effective if the stone was mined near a highroad (the Bradford and Wakefield road). (20) The transporting of ironstone is a good indication that Gildersome's fuel (trees) had run low.

|

Above: In this clipping from the 1824 Enclosure Map of Gildersome, the perimeter of the fields containing the Stone Pitts is within the dashed lines. Lumb Bottom appears at the top and the intersection of Nipshaw Lane and the Bradford and Wakefield road can be seen at the bottom.

Close to one hundred years after Domesday, Radulfo de Gildhus became the first resident of Gildersome to appear in the Court Rolls of Yorkshire. (21) His very appearance in the Court Rolls marked Mr. de Gildus as a man of property, but by what means was his wealth acquired? In an economic study that assessed wealth in terms of shillings per square mile (1334), Gildersome’s value was estimated at 47 shillings. This was on a par with Drighlington, though less than Morley, which was valued at 57 shillings. Perhaps surprisingly, Gildersome’s value was greater than that of Farnley, Gomersal and Batley. (22) In a later evaluation (c1600) Gildersome’s value was again equal to Drighlington, but higher than most other villages in the surrounding area, including Morley. (23) What is the explanation for this apparent wealth, given that Barnard’s survey of 1577 described Gildersome as a "hamlet having about twenty dwellings, where it was easy to settle and encroach on the wastes?" (24) Almost certainly ironworking, and later coal mining, is the answer.

It's unknown where the first serious mining operations were located, though this is likely to be where the necessary resources would be most readily available. Two sites that fit the bill would be those at Gildersome Bottoms and Lumb Bottom. Evidence suggests that both of these had sufficient wood and water resources with which to operate a smithy. The site at Lumb Bottom, however, was not located in the village and is most likely connected with the 15th and 16th century excavations at the Stone Pits close by. On the other hand, the site at Stony Gate was richer and easier to mine. It's close to the modern village and this proximity suggests that it could have been the starting point from which the present village eventually developed. In addition, the site of the Manor House on what was his lordship's demesne land suggests an 800 year occupation for both. The first furnace site could have been somewhere in the Bottoms, with the charcoalers exploiting timber resources up the gentle slope toward the ridge of Moorhead. In due course, the woods would have been cleared eastwards out of Stony Gate between Farnley Wood Beck and Harthill, exposing further outcroppings of ironstone along the way and eventually terminating at Gilead House. Perhaps the area cleared of its trees was the assart of Gildhus alluded to in the Award of 1233? (25)

It's unknown where the first serious mining operations were located, though this is likely to be where the necessary resources would be most readily available. Two sites that fit the bill would be those at Gildersome Bottoms and Lumb Bottom. Evidence suggests that both of these had sufficient wood and water resources with which to operate a smithy. The site at Lumb Bottom, however, was not located in the village and is most likely connected with the 15th and 16th century excavations at the Stone Pits close by. On the other hand, the site at Stony Gate was richer and easier to mine. It's close to the modern village and this proximity suggests that it could have been the starting point from which the present village eventually developed. In addition, the site of the Manor House on what was his lordship's demesne land suggests an 800 year occupation for both. The first furnace site could have been somewhere in the Bottoms, with the charcoalers exploiting timber resources up the gentle slope toward the ridge of Moorhead. In due course, the woods would have been cleared eastwards out of Stony Gate between Farnley Wood Beck and Harthill, exposing further outcroppings of ironstone along the way and eventually terminating at Gilead House. Perhaps the area cleared of its trees was the assart of Gildhus alluded to in the Award of 1233? (25)

Click to enlarge the image.

Click to enlarge the image.

The Smelting Process

During the Iron Age, iron smelting was a cottage industry with each step in the process undertaken by a small group of individuals. As the demand for iron grew, the process became more intensive, giving rise to specialisation. One of the specialists involved was the smelter or smith. After the ore had been dug, it was prepared and delivered to the smith for smelting. The word “smelting” is not entirely correct, rather it was an ancient process of producing iron that could be hand worked, but was not pure enough for casting in a mould (casting came with the development of the blast furnace). The process required a forge, called a bloomery, which was built of clay, fuelled by charcoal and enhanced by human-powered bellows. The heat derived therefrom allowed the relatively pure iron to be released from the chemical bond it shared with other ingredients (the residue is known as slag). From the onset of this technology, the bloomery would have been located at or quite close to the mining site in order to minimise the requirement for transportation. However, with the introduction of water-powered mechanical bellows in the 15th century, bloomery sites became fixed near an adequate water source. Any increase in transportation costs would have been offset by increased production.

(Above right: Gravers dig into an exposed bank while others work in pits dug into higher ground. The artist cut out the banks of the hill to render the workers inside visible). (26)

Another specialist, vital to the smelting process, was the Charcoaler, the person responsible for converting timber into charcoal: a more efficient form of fuel with which to power the bloomery. To the detriment of nearby woodland resources, innumerable acres of greenwood would have been consumed annually to keep the smelter’s fires burning. In the iron producing areas of West Yorkshire, the management of manorial woodland was simply insufficient to prevent this destruction, with charcoal production resulting in whole forests disappearing in the space of a few hundred years.

During the Iron Age, iron smelting was a cottage industry with each step in the process undertaken by a small group of individuals. As the demand for iron grew, the process became more intensive, giving rise to specialisation. One of the specialists involved was the smelter or smith. After the ore had been dug, it was prepared and delivered to the smith for smelting. The word “smelting” is not entirely correct, rather it was an ancient process of producing iron that could be hand worked, but was not pure enough for casting in a mould (casting came with the development of the blast furnace). The process required a forge, called a bloomery, which was built of clay, fuelled by charcoal and enhanced by human-powered bellows. The heat derived therefrom allowed the relatively pure iron to be released from the chemical bond it shared with other ingredients (the residue is known as slag). From the onset of this technology, the bloomery would have been located at or quite close to the mining site in order to minimise the requirement for transportation. However, with the introduction of water-powered mechanical bellows in the 15th century, bloomery sites became fixed near an adequate water source. Any increase in transportation costs would have been offset by increased production.

(Above right: Gravers dig into an exposed bank while others work in pits dug into higher ground. The artist cut out the banks of the hill to render the workers inside visible). (26)

Another specialist, vital to the smelting process, was the Charcoaler, the person responsible for converting timber into charcoal: a more efficient form of fuel with which to power the bloomery. To the detriment of nearby woodland resources, innumerable acres of greenwood would have been consumed annually to keep the smelter’s fires burning. In the iron producing areas of West Yorkshire, the management of manorial woodland was simply insufficient to prevent this destruction, with charcoal production resulting in whole forests disappearing in the space of a few hundred years.

Sometime during the 1400s the mechanical bellows powered by a watermill was introduced to West Yorkshire. It’s fairly certain that Gildersome had at least one of these mills, possibly located in the Bottoms, or Philadelphia. The Yorkshire Fines list four deeds concerning Gildersome, other townships and watermills, the earliest is dated 1503. Although the first three deeds fall short of connecting Gildersome specifically with a watermill, the fourth (1579) makes the following revelation: (27)

Manors of Morley, Gyldersome, and Howley, and 100 messuages, 40 cottages, and 4 watermills with lands....

Watermills were beneficial to ironworks through the increase in productivity, though the benefit came at considerable cost to Gildersome’s woodlands. By the mid 1500s Gildersome ironstone was being transported to smithies at Shipley, Farnley, and probably Birstall, indicating that Gildersome's fuel was in short supply.

Aside from Stoney Gate being a prime contender for a watermill, the following are two other sites that could have supported an ironworking mill:

Aside from Stoney Gate being a prime contender for a watermill, the following are two other sites that could have supported an ironworking mill:

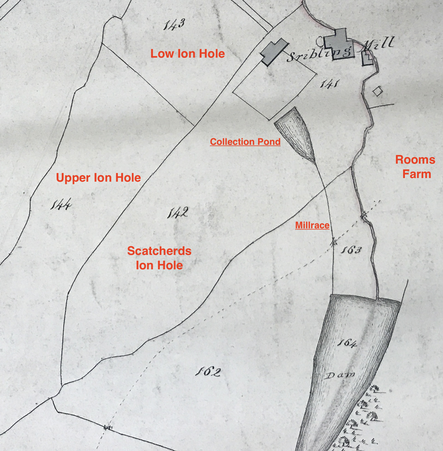

|

This clipping taken from the 1800 Enclosure Map for Gildersome, right, reveals a possible ironworking site at Philadelphia near the bottom of Dean Beck (the squiggly line on the right, running from the dam and north past the mill). The collection pond is serving the late 1700s scribbling mill (Philadelphia Mill). It's possible the same site hosted a mill or mills for centuries, either for ironworking or grinding grains or both. The three fields surrounding the collection pond, called Ion Hole in the 1843 Tithe survey, were called Johnny or John Hole in earlier deeds, both were names associated with coal mining, such as the Joan Coal bed.

|

Click to view a larger image.

Click to view a larger image.

Though not in Gildersome, Cockersdale is close by. In a clipping from an 1852 O.S. map, right, the red lines represent the Black Bed seam (ironstone bearing) which is close to the surface. Its found on both sides of the beck indicating that the plane of the strata in that area is relatively close to horizontal. Due to the presence of a geological fault, the seams begin near Cockersdale and run along both sides of Tong Beck to the confluence of with Pudsey Beck and beyond. If you ever wondered what made Farnley Wood disappear, the answer may lie in the red lines contained in this map. The eastern seam follows Pudsey Beck downstream. About ¾ of a mile north of Cockersdale, near the beck in Farnley, is a field called Cinderhill. Proceed another ½ mile, or so downstream, and there's another Cinderhill near to the old Farnley Smithies. A third furnace site is suggested, this time in the centre of Farnley near Pitt Hill, it's described in the list of fields as, "Cinder Oven and Waste." At Domesday, Farnley Wood may have contained 2,000 acres, more or less, but by 1451, the earliest report of its size, it was reported to have been close to 600 acres (by the early 19th century another 300 acres had been consumed). All this indicates that Farnley's wood resources were under intense exploitation and that ironworking may have been prime contributor.

The green line in the lower left of the map indicates the Tankersley ironstone which runs into Drighlington. It's possible that these ore beds and the Tong beck sites were worked long before ironworking began in Gildersome.

In Cockersdale, a series of ponds with a mill race can be seen on the map. The valuable iron ore in its immediate vicinity leads one to the conclusion that this spot has been used as a mill site since the Middle Ages. Traces of the ponds and mill race can still be seen today.

The green line in the lower left of the map indicates the Tankersley ironstone which runs into Drighlington. It's possible that these ore beds and the Tong beck sites were worked long before ironworking began in Gildersome.

In Cockersdale, a series of ponds with a mill race can be seen on the map. The valuable iron ore in its immediate vicinity leads one to the conclusion that this spot has been used as a mill site since the Middle Ages. Traces of the ponds and mill race can still be seen today.

Summary:

We have argued that the discovery of ironstone deposits would have made the area around Gildersome into an attractive location for early ironworking. What probably began as a cottage industry providing materials for domestic use gradually developed into a well organised operation that created considerable wealth for landowners and employment for their servants. We have also established that Gildersome’s ironworking industry had been facilitated by the ready availability of exploitable resources. It is perhaps significant that the depletion of one of those resources ultimately resulted in the industry’s decline. However, the real significance of Gildersome’s ironworking history may reside in its legacy. It is not beyond the boundaries of possibility that the same depletion of the woodlands ultimately resulted in the establishment of the assart of Gildhus and eventually to Gildersome itself.

We have argued that the discovery of ironstone deposits would have made the area around Gildersome into an attractive location for early ironworking. What probably began as a cottage industry providing materials for domestic use gradually developed into a well organised operation that created considerable wealth for landowners and employment for their servants. We have also established that Gildersome’s ironworking industry had been facilitated by the ready availability of exploitable resources. It is perhaps significant that the depletion of one of those resources ultimately resulted in the industry’s decline. However, the real significance of Gildersome’s ironworking history may reside in its legacy. It is not beyond the boundaries of possibility that the same depletion of the woodlands ultimately resulted in the establishment of the assart of Gildhus and eventually to Gildersome itself.

Sources:

(1) Roman Roads of Britain: http://www.romanroads.org/gazetteer/gazetteer_home.html.

(2) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(3) The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Volume 68, page 1996.

(4) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 14

(5) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

(6) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(7) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(8) Ibid

(9) Bernard Hobson M.Sc., F.G.S. (1921): The West Riding of Yorkshire

(10) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(11) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(12) Ibid

(13) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(14) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(15) Ibid

(16) Ibid.

(17) Ibid.

(18) Ibid.

(19) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(20) The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Volume 68, page 1996.

(21) THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-THIRD YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1176 - 1177 VOL. 26 Pg 79

(22) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 29

(23) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 30

(24) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire

Archaeological Journal, 88:1, 159-175, DOI: 10.1080/00844276.2016.1192798

(25) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

(26) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(27) 'Yorkshire Fines: 1579', in Feet of Fines of the Tudor Period [Yorks]: Part 2, 1571-83, ed. Francis Collins (Leeds, 1888), pp. 124-146.

British History Onlinehttp://www.british-history.ac.uk/feet-of-fines-yorks/vol2/pp124-146 [accessed 6 May 2019].

Between Robert Savile, esq. and Francis Leeke, kt.

(1) Roman Roads of Britain: http://www.romanroads.org/gazetteer/gazetteer_home.html.

(2) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(3) The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Volume 68, page 1996.

(4) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 14

(5) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

(6) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(7) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(8) Ibid

(9) Bernard Hobson M.Sc., F.G.S. (1921): The West Riding of Yorkshire

(10) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(11) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(12) Ibid

(13) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(14) Geological Survey of England and Wales, Revised 1932, Sheet 217 SE.

(15) Ibid

(16) Ibid.

(17) Ibid.

(18) Ibid.

(19) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal,

(20) The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Volume 68, page 1996.

(21) THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-THIRD YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1176 - 1177 VOL. 26 Pg 79

(22) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 29

(23) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 4, Map 30

(24) G.D. Newton (2016) Farnley Smithies, Leeds: An Elizabethan Iron Works and its Sources of Ironstone and Charcoal, Yorkshire

Archaeological Journal, 88:1, 159-175, DOI: 10.1080/00844276.2016.1192798

(25) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

(26) Georg Agricola: De re metallica (1556) (translation, 'On the Nature of Metals')

(27) 'Yorkshire Fines: 1579', in Feet of Fines of the Tudor Period [Yorks]: Part 2, 1571-83, ed. Francis Collins (Leeds, 1888), pp. 124-146.

British History Onlinehttp://www.british-history.ac.uk/feet-of-fines-yorks/vol2/pp124-146 [accessed 6 May 2019].

Between Robert Savile, esq. and Francis Leeke, kt.