|

Medieval Gildersome

|

It must be noted that I am not a scholar of languages or a historian but rather a researcher. The theories I present are based on my interpretation of the available information.

|

With these few words, recorded in Latin in the 33rd year of the reign of King Henry II (1176-1177), the recorded history of Gildersome began:

"Idem vicecomes reddit compotum de catallis fugitivorum et eorum qui perierunt judicio aque per assisam de norhanton de anno preterito. Quorum nomina subscribuntur. ................. De Radulfo del Gildhus . xxi. s. ...........

In thesauro liberavit. Et quietus est." *

A possible translation is as follows:

"The sheriff of Yorkshire's expenses for the judgment of sizing the chattels of fugitives and of those who perished by the ordeal of water at the assizes in Northampton in the past year. Their names are subscribed. ....... For Radulfo of Gildersome 21s........Paid out from the Treasury. These matters are concluded."

The next surviving record was made 3 or 4 years later (1180-1181):

De oblatis Curie.

Idem vicecomes redd. comp. de .vj. s. et .viij. d. de Rogero de Gildehusum. Et de dim. m. de Alwin de Horton’ quia retraxerunt se de appellatione sua. In thesauro liberavit in ij. talliis.

Et quietus est. **

A possible translation is as follows:

"Outstanding Debts Carried Forward from Last Year.

The Sheriff to pay compensation of six shillings and eight pence to Roger de Gildersome and half a mark to Alwin de Horton because they have withdrawn their appeal. Paid in two payments. This matter is concluded."

* From: THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-THIRD YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1176 - 1177 VOL. 26 Pg 79

** From: THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1180 - 1181 VOL. 30 Pg 44

"Idem vicecomes reddit compotum de catallis fugitivorum et eorum qui perierunt judicio aque per assisam de norhanton de anno preterito. Quorum nomina subscribuntur. ................. De Radulfo del Gildhus . xxi. s. ...........

In thesauro liberavit. Et quietus est." *

A possible translation is as follows:

"The sheriff of Yorkshire's expenses for the judgment of sizing the chattels of fugitives and of those who perished by the ordeal of water at the assizes in Northampton in the past year. Their names are subscribed. ....... For Radulfo of Gildersome 21s........Paid out from the Treasury. These matters are concluded."

The next surviving record was made 3 or 4 years later (1180-1181):

De oblatis Curie.

Idem vicecomes redd. comp. de .vj. s. et .viij. d. de Rogero de Gildehusum. Et de dim. m. de Alwin de Horton’ quia retraxerunt se de appellatione sua. In thesauro liberavit in ij. talliis.

Et quietus est. **

A possible translation is as follows:

"Outstanding Debts Carried Forward from Last Year.

The Sheriff to pay compensation of six shillings and eight pence to Roger de Gildersome and half a mark to Alwin de Horton because they have withdrawn their appeal. Paid in two payments. This matter is concluded."

* From: THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-THIRD YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1176 - 1177 VOL. 26 Pg 79

** From: THE GREAT ROLL OF THE PIPE for the TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR OF THE REIGN of KING HENRY the SECOND A.D. 1180 - 1181 VOL. 30 Pg 44

From "The Story of Morley"

From "The Story of Morley"

From 1176 and for several hundred years thereafter, the name Gildhus, in various forms, was the name which appeared consistently in contemporary documents. It may have been a variation of a surviving Scandinavian or Saxon name such as Gilhus or Gildas, or possibly a guild hall or Gildhus as was spoken then.

Gildersome did not appear in the Domesday Book. Was it an oversight made by the King's commissioners or an omission, deliberate or not, on the part of the local representatives whose duty it was to faithfully report all towns and villages and their assets to those commissioners? Nearly half of the towns and villages in the Wapentake of Morley, mostly to the west, went unreported either due to their remoteness or, more likely, Norman reprisals. In fact, during the period between the Conquest and Domesday known as the 'Harrying of the North.' a good deal of West Yorkshire had been decimated so that by the time of the domesday inspections many existing manors were recorded as waste (either nothing of value or inhabitants or both).

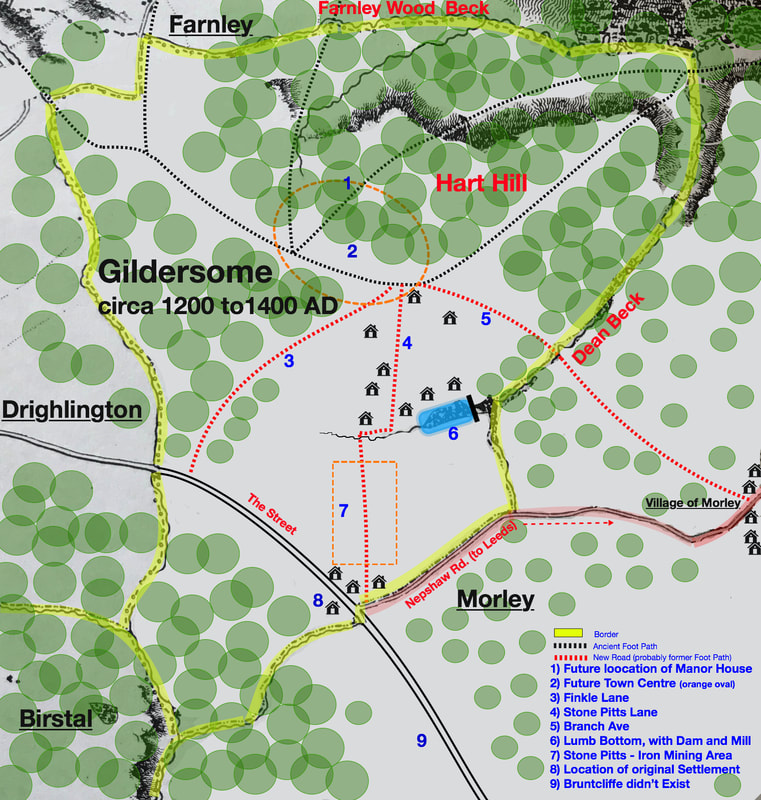

So from that time until its establishment as a manor, possibly around 1150, Gildersome was probably considered a berewick of Morley (a detached portion of land belonging to a medieval manor). If any small settlement existed there, its likeliest location would have been at the top of Nepshaw Lane at The Street (the section of the Bradford & Wakefield road that ran through Gildersome). The road network provided easy access to nearby markets, but also found near the intersection was abundant water, woodland suitable for conversion to agricultural use, and mineral wealth in the form of coal and ironstone, some of the most valuable commodities in the medieval world. Their presence helps to support the notion that such an important crossroads was not devoid of human activity. In fact, a small hamlet of 2 to 4 families is certainly not beyond the realm of possibilities.

Proto-Gildersome may have included one or a few of the following improved sites:

a Farmstead

a Toll Bar and Toll-Keeper's House

an Inn with a Smithy

Iron Mining and Smelting

a Woodmen's or Charcoal Burner's camp

Perhaps a Guild House stood nearby, whose presence gave rise to the name Gildhus. It could have held a religious shrine or a band of eremite monks who worshiped in isolation (Some monastic enclaves did engage in iron smelting). These two examples of gilds and others not mentioned were common all over Yorkshire in the middle ages.

If not a religious guild then maybe a trade association such as a guild of iron-founders or miners who plied their trade at the Stone Pitts.

Whatever remained to be found of those ancient days will no doubt remain a mystery as commercial development and the M621 have spoiled any opportunity for archaeological research. Recently, all of the fields called the Nipshaws, the Windmill Close and the Mill Fields, including Lumb Bottom have been scraped clean, awaiting development. More's the pity!

In the early 1100s, King Henry I granted dominion over the ancient parish of Batley to the Nostell Priory which was located near Wakefield. In 1233, a dispute between the Priory and the parish of Leeds over the northern boundary of Batley parish, resulted in Batley's northern border being fixed at Farnley Wood Beck running between Farnley Wood and the assart of Gildus (Gildersome). This put Gildersome firmly in Batley parish where it remained until the 1870s when the Parish of Gildersome was created.

The two court roll references to Gildhus (above) establish that in 1176 Dean Wood had been settled, and the boundary dispute of 1233 describes it as an assart, woods cleared for farmland, and not a manor or even a hamlet. The West Yorkshire Archaeological to A.D. 1500 makes a point that Gildersome began as cleared land well before the Norman Conquest, however the first mention of Gildersome as a manor is not until 1280. Unfortunately, any record of this occurring has been lost.

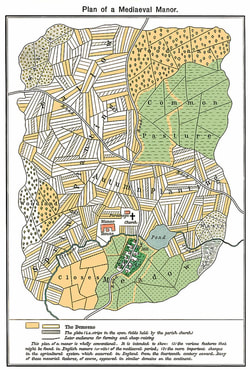

The new Lord of Gildhus, according to the fashion of the times, would have received approximately 1,000 acres in total (very close in acreage to the present size of Gildersome). Some would have been allotted specifically for his use, in perpetuity, for maintenance of the manor. Such plots of land, in the feudal system were called the demesne (de-MAYN), which contained all the land retained by the lord of the manor for his own use and support. It was not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house. A portion of the demesne lands, called the lord's waste, served as public roads and common pasture land for the lord and his tenants. Most of the remainder of the land in the manor was leased out by the lord to others as sub-tenants in exchange for fees or service or both. Lower rung villagers, villeins and serfs, were required to work the demesne a specified number of hours per year.

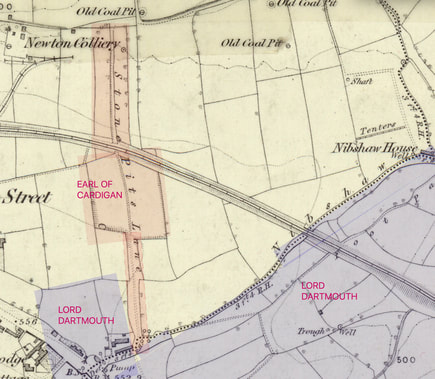

Gildhus' boundaries were certainly easy to configure as, for the most part, they consisted almost entirely of natural features. Those features are, Farnley Wood Beck to the north, Dean Beck to the east, Howden Clough in the south and Andrew Beck to the west. By the addition of Nepshaw Lane as part of its boundary, Gildersome gained access to the important intersection at The Street and Leeds Road (Nepshaw Lane) which they shared with the Manor of Morley. It was often the case that, now and then, that Gildersome and Morley shared the same lord but when it didn't, sharing the Nepshaw boundary may have caused contention and perhaps was contested for several centuries until a proper survey could fix the line. This may have occured circa 1671 when Gildersome and Morley belonged to the same lord Saville. Upon his death, the Earl of Cardigan and Lord Dartmouth divided Gildersome and Morley, with Gildersome going to Cardigan.

Early on, an administrative building, sometimes called a hall, would certainly have been built. This Hall housed a manorial court, primarily dealing with local disputes, as well as offices for other important agents. Those offices would include a bailiff, a reeve (lord's overseer), a clerk, a forester to manage the woodland, a ditch reeve (an expert in drainage) and a toll keeper. The construction of a manor house was optional and left to the whim of the lord. If, early on, a manor house was built, it would have been made of wood, like most everything built in England's middle ages, as only important constructions were made of stone.

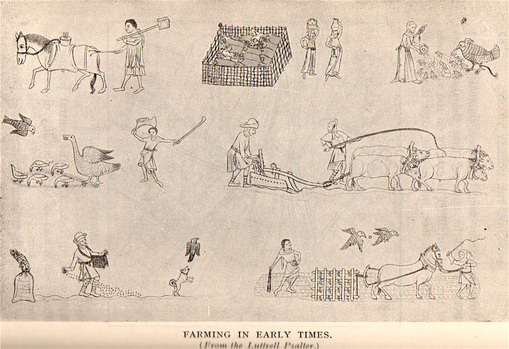

Ordinary life in England's middle ages was tightly regulated and stratified. Everyone knew his or her place. This was especially so for countless generations of the lower classes who were expected to work the same fields from birth until death without change. I could continue but there's a wealth of fascinating material written about village life during the middle ages, both in books and on the internet. I encourage those curious about early Gildersome to start with "Medieval Manor" on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manor

Gildersome did not appear in the Domesday Book. Was it an oversight made by the King's commissioners or an omission, deliberate or not, on the part of the local representatives whose duty it was to faithfully report all towns and villages and their assets to those commissioners? Nearly half of the towns and villages in the Wapentake of Morley, mostly to the west, went unreported either due to their remoteness or, more likely, Norman reprisals. In fact, during the period between the Conquest and Domesday known as the 'Harrying of the North.' a good deal of West Yorkshire had been decimated so that by the time of the domesday inspections many existing manors were recorded as waste (either nothing of value or inhabitants or both).

So from that time until its establishment as a manor, possibly around 1150, Gildersome was probably considered a berewick of Morley (a detached portion of land belonging to a medieval manor). If any small settlement existed there, its likeliest location would have been at the top of Nepshaw Lane at The Street (the section of the Bradford & Wakefield road that ran through Gildersome). The road network provided easy access to nearby markets, but also found near the intersection was abundant water, woodland suitable for conversion to agricultural use, and mineral wealth in the form of coal and ironstone, some of the most valuable commodities in the medieval world. Their presence helps to support the notion that such an important crossroads was not devoid of human activity. In fact, a small hamlet of 2 to 4 families is certainly not beyond the realm of possibilities.

Proto-Gildersome may have included one or a few of the following improved sites:

a Farmstead

a Toll Bar and Toll-Keeper's House

an Inn with a Smithy

Iron Mining and Smelting

a Woodmen's or Charcoal Burner's camp

Perhaps a Guild House stood nearby, whose presence gave rise to the name Gildhus. It could have held a religious shrine or a band of eremite monks who worshiped in isolation (Some monastic enclaves did engage in iron smelting). These two examples of gilds and others not mentioned were common all over Yorkshire in the middle ages.

If not a religious guild then maybe a trade association such as a guild of iron-founders or miners who plied their trade at the Stone Pitts.

Whatever remained to be found of those ancient days will no doubt remain a mystery as commercial development and the M621 have spoiled any opportunity for archaeological research. Recently, all of the fields called the Nipshaws, the Windmill Close and the Mill Fields, including Lumb Bottom have been scraped clean, awaiting development. More's the pity!

In the early 1100s, King Henry I granted dominion over the ancient parish of Batley to the Nostell Priory which was located near Wakefield. In 1233, a dispute between the Priory and the parish of Leeds over the northern boundary of Batley parish, resulted in Batley's northern border being fixed at Farnley Wood Beck running between Farnley Wood and the assart of Gildus (Gildersome). This put Gildersome firmly in Batley parish where it remained until the 1870s when the Parish of Gildersome was created.

The two court roll references to Gildhus (above) establish that in 1176 Dean Wood had been settled, and the boundary dispute of 1233 describes it as an assart, woods cleared for farmland, and not a manor or even a hamlet. The West Yorkshire Archaeological to A.D. 1500 makes a point that Gildersome began as cleared land well before the Norman Conquest, however the first mention of Gildersome as a manor is not until 1280. Unfortunately, any record of this occurring has been lost.

The new Lord of Gildhus, according to the fashion of the times, would have received approximately 1,000 acres in total (very close in acreage to the present size of Gildersome). Some would have been allotted specifically for his use, in perpetuity, for maintenance of the manor. Such plots of land, in the feudal system were called the demesne (de-MAYN), which contained all the land retained by the lord of the manor for his own use and support. It was not necessarily all contiguous to the manor house. A portion of the demesne lands, called the lord's waste, served as public roads and common pasture land for the lord and his tenants. Most of the remainder of the land in the manor was leased out by the lord to others as sub-tenants in exchange for fees or service or both. Lower rung villagers, villeins and serfs, were required to work the demesne a specified number of hours per year.

Gildhus' boundaries were certainly easy to configure as, for the most part, they consisted almost entirely of natural features. Those features are, Farnley Wood Beck to the north, Dean Beck to the east, Howden Clough in the south and Andrew Beck to the west. By the addition of Nepshaw Lane as part of its boundary, Gildersome gained access to the important intersection at The Street and Leeds Road (Nepshaw Lane) which they shared with the Manor of Morley. It was often the case that, now and then, that Gildersome and Morley shared the same lord but when it didn't, sharing the Nepshaw boundary may have caused contention and perhaps was contested for several centuries until a proper survey could fix the line. This may have occured circa 1671 when Gildersome and Morley belonged to the same lord Saville. Upon his death, the Earl of Cardigan and Lord Dartmouth divided Gildersome and Morley, with Gildersome going to Cardigan.

Early on, an administrative building, sometimes called a hall, would certainly have been built. This Hall housed a manorial court, primarily dealing with local disputes, as well as offices for other important agents. Those offices would include a bailiff, a reeve (lord's overseer), a clerk, a forester to manage the woodland, a ditch reeve (an expert in drainage) and a toll keeper. The construction of a manor house was optional and left to the whim of the lord. If, early on, a manor house was built, it would have been made of wood, like most everything built in England's middle ages, as only important constructions were made of stone.

Ordinary life in England's middle ages was tightly regulated and stratified. Everyone knew his or her place. This was especially so for countless generations of the lower classes who were expected to work the same fields from birth until death without change. I could continue but there's a wealth of fascinating material written about village life during the middle ages, both in books and on the internet. I encourage those curious about early Gildersome to start with "Medieval Manor" on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manor

The Lords of the Manor

The Domesday Book entries for Morley named Dunstan (either a Saxon or a Dane) as the former Lord. Morley's six carucates (approximately 720 acres) of land and the tenancy then passed to Ilbert de Lacy, a Norman. Prior to 1066, Dunstan held title to over a dozen manors but whether he continued in possession of any as under-tenant to de Lacy is unknown. Because of the large gaps in the surviving records from that time, it's surmised that in the early 1100s, most of the land in Morley was held jointly by Ralph de L'isle and Robert de Beeston. It was both of those under-tenants to de Lacy who gave land in Morley to the Nostell Priory as mentioned above.

It's unfortunate that the earliest (1176-77) surviving mention of Gildersome concerns Radulfo de Gildhus who was either executed after an 'ordeal by water' or a fugitive from justice for supposed crimes (see, the Court Roll entries above). Radulfo was on a list with approximately 60 other men who had had their property seized, all were either fugitives or were executed. What's interesting is that the expense for handling his case was the second highest of the lot, so he must either have been a man of some means or there was difficulty with the seizure of his property, a common practice when a greater lord needed money. In the Court Roll entry, three years later, Rogero de Gildhusum and Alwin de Horton may have been Radulfo's sons who petitioned to have Radulfo's properties returned.

By 1200, a descendant of Ralph de L'isle, named William de L'isle, held the manor of Morley of which Gildhus may have been a part. William de L'ise had two daughters, one of these, Eufemia, married Nicholas de Rotherfield, and the other, Helewisia, married Marmaduke Darel (see: 1226, Feet of Fines, below). In 1226, a judgment levied between the two sisters and their husbands, divided their father's lands and Gildhus and Morley passed to the Rotherfields.

Sometime during the next 60 years or so, the possession of the Manor of Gildhus must have passed to a daughter or granddaughter of Eufemia and Nicholas and subsequently out of the Rotherfield line. As near as I can make out, in 1280, William de Rither (Ryther) marries a woman named Lucy who brings with her the manor of Gildhus as part of her dowery. The agreement contained the condition that if Lucy were to die without heirs, the manor would revert to the Ross family, to whom Lucy was somehow related. Apparently, Lucy does have children and Gildersome remains in the Ryther family for many generations to come. (see: 1280, below), This conclusion is supported by a 1304 Charter Roll record which states, "Grant to William de Rythre, and his heirs, of free warren in all their demesne lands in Scarthecroft, Hornyton and Gyldusum , co. York.". Wikipedia's definition of free warren is as follows: "....a type of franchise or privilege conveyed by a sovereign in mediaeval England to a subject, promising to hold them harmless for killing game of certain species within a stipulated area, usually a wood or small forest. .............The privilege of free warren was a reciprocal relationship. The grantee of the warren was granted an exemption from the law (under which all game in the realm was property of the sovereign), but the grantee owed the sovereign the stewardship and protection of the game from all others who might wish to hunt it."

Meanwhile, back in Morley during the 14th century, a marriage that took place between a Rotherfield and a Mirfield which resulted in the manor of Morley passing into the Mirfield family. Though there are no records to support it, Gildersome was acquired by the same Mirfield family, either through that same marriage, a different marriage within the same families or through some other cause. Whatever the arrangements were, eventually, the Mirfields of Howley came to control both the the manors of Gildersome and Morley. This is born out by the '1360 - 1370' record, below, in which a 'William de Gildersome' is clearly a Mirfield, as this 1461 will, kept in the Registry at York, bears witness: " Testamentum Oliveri Myrfeld Armigeri ..........First I wille that my feffis that air enfeffed in al my lordschippes - in the townes of Mirfeld, Dighton, Egerton, Gleydholte, Heyton, hopton, Batley, Holey, Morley, Gildosome, Bolton, Chekylay, Leede, Newstede, Halyfax, Wakefelde, Westerton, with al theire appurtenaunces, make a state of theim - to William Mirfeld my son and to his eyeres of his body......"

In time, both the manors of Gildersome and Morley were handed down to the Savile family who established themselves at Howley Hall. Philip Booth, in his history, wrote, "Sir John Savile, who died on Aug. 31st, 1630, at Howley Hall, was certified to be possessed of the Manors of Headingley, Batley, Morley, East Ardsley, Woodchurch and Gildersome, in addition to lands in Wakefield, Dewsbury and other places. His descendant, James Savile, 2nd Earl of Sussex, who died in 1671, left no heir, so the Manor passed to the Cardigan family, into which a Savile had married."

Today, the Earl of Cardigan and Marquess of Ailesbury titles have merged and David Brudenell-Bruce is the present titular lord of Gildersome Manor.

The Domesday Book entries for Morley named Dunstan (either a Saxon or a Dane) as the former Lord. Morley's six carucates (approximately 720 acres) of land and the tenancy then passed to Ilbert de Lacy, a Norman. Prior to 1066, Dunstan held title to over a dozen manors but whether he continued in possession of any as under-tenant to de Lacy is unknown. Because of the large gaps in the surviving records from that time, it's surmised that in the early 1100s, most of the land in Morley was held jointly by Ralph de L'isle and Robert de Beeston. It was both of those under-tenants to de Lacy who gave land in Morley to the Nostell Priory as mentioned above.

It's unfortunate that the earliest (1176-77) surviving mention of Gildersome concerns Radulfo de Gildhus who was either executed after an 'ordeal by water' or a fugitive from justice for supposed crimes (see, the Court Roll entries above). Radulfo was on a list with approximately 60 other men who had had their property seized, all were either fugitives or were executed. What's interesting is that the expense for handling his case was the second highest of the lot, so he must either have been a man of some means or there was difficulty with the seizure of his property, a common practice when a greater lord needed money. In the Court Roll entry, three years later, Rogero de Gildhusum and Alwin de Horton may have been Radulfo's sons who petitioned to have Radulfo's properties returned.

By 1200, a descendant of Ralph de L'isle, named William de L'isle, held the manor of Morley of which Gildhus may have been a part. William de L'ise had two daughters, one of these, Eufemia, married Nicholas de Rotherfield, and the other, Helewisia, married Marmaduke Darel (see: 1226, Feet of Fines, below). In 1226, a judgment levied between the two sisters and their husbands, divided their father's lands and Gildhus and Morley passed to the Rotherfields.

Sometime during the next 60 years or so, the possession of the Manor of Gildhus must have passed to a daughter or granddaughter of Eufemia and Nicholas and subsequently out of the Rotherfield line. As near as I can make out, in 1280, William de Rither (Ryther) marries a woman named Lucy who brings with her the manor of Gildhus as part of her dowery. The agreement contained the condition that if Lucy were to die without heirs, the manor would revert to the Ross family, to whom Lucy was somehow related. Apparently, Lucy does have children and Gildersome remains in the Ryther family for many generations to come. (see: 1280, below), This conclusion is supported by a 1304 Charter Roll record which states, "Grant to William de Rythre, and his heirs, of free warren in all their demesne lands in Scarthecroft, Hornyton and Gyldusum , co. York.". Wikipedia's definition of free warren is as follows: "....a type of franchise or privilege conveyed by a sovereign in mediaeval England to a subject, promising to hold them harmless for killing game of certain species within a stipulated area, usually a wood or small forest. .............The privilege of free warren was a reciprocal relationship. The grantee of the warren was granted an exemption from the law (under which all game in the realm was property of the sovereign), but the grantee owed the sovereign the stewardship and protection of the game from all others who might wish to hunt it."

Meanwhile, back in Morley during the 14th century, a marriage that took place between a Rotherfield and a Mirfield which resulted in the manor of Morley passing into the Mirfield family. Though there are no records to support it, Gildersome was acquired by the same Mirfield family, either through that same marriage, a different marriage within the same families or through some other cause. Whatever the arrangements were, eventually, the Mirfields of Howley came to control both the the manors of Gildersome and Morley. This is born out by the '1360 - 1370' record, below, in which a 'William de Gildersome' is clearly a Mirfield, as this 1461 will, kept in the Registry at York, bears witness: " Testamentum Oliveri Myrfeld Armigeri ..........First I wille that my feffis that air enfeffed in al my lordschippes - in the townes of Mirfeld, Dighton, Egerton, Gleydholte, Heyton, hopton, Batley, Holey, Morley, Gildosome, Bolton, Chekylay, Leede, Newstede, Halyfax, Wakefelde, Westerton, with al theire appurtenaunces, make a state of theim - to William Mirfeld my son and to his eyeres of his body......"

In time, both the manors of Gildersome and Morley were handed down to the Savile family who established themselves at Howley Hall. Philip Booth, in his history, wrote, "Sir John Savile, who died on Aug. 31st, 1630, at Howley Hall, was certified to be possessed of the Manors of Headingley, Batley, Morley, East Ardsley, Woodchurch and Gildersome, in addition to lands in Wakefield, Dewsbury and other places. His descendant, James Savile, 2nd Earl of Sussex, who died in 1671, left no heir, so the Manor passed to the Cardigan family, into which a Savile had married."

Today, the Earl of Cardigan and Marquess of Ailesbury titles have merged and David Brudenell-Bruce is the present titular lord of Gildersome Manor.

Stone Pits at Benton Grange, similar to how the area around Stone Pitts Ln. appeared.

Stone Pits at Benton Grange, similar to how the area around Stone Pitts Ln. appeared.

Theory Regarding Gildersome's Origin

This theory postulates that the early interest in Gildersome centered around the top of Nepshaw Lane and its intersection with The Street. Starting from there the clearcutting expanded in a northward direction. It must be remembered that this theory is based upon the facts as they are known and what was generally happening in the region in the time, the real events may have been completely different.

England in the middle ages, was a wooden world. The market for wood and charcoal was insatiable and the demand kept on growing. Gildersome had what many other existing manors lacked, or had exhausted by the 12th century, easy access to an extensive and relatively untouched woodland. The commercial potential was sizeable, profits from the sale of timber and charcoal alone would have exceeded those of an established manor whose economy was entirely farm based. Thanks to a good road network and proximity to many nearby markets, including the river ports of Leeds and Wakefield, Gildersome's yield probably suffered from no lack of buyers, even when times were bad.

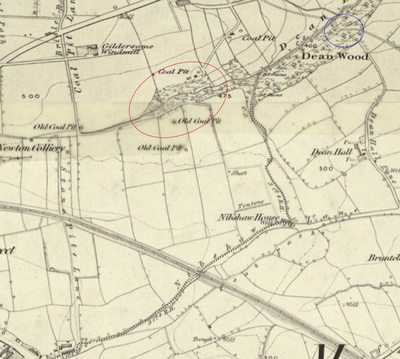

Gildersome's other economic asset was iron ore called ironstone, a sandstone, which was found over a large portion of West Yorkshire and mined extensively during the middle ages. Ironstone was apparently abundant and easily accessible near the top of Nepshaw Lane and Old Stone Pitts Road and along The Street's south side where the land fell away. It's highly likely that ironstone mining and a crude furnace, called a bloomery, could have have been in continuous operation for quite some time. If so, the distinctive stone pits and cinder mounds, left by the previous miners, would have been easily spotted and exploited by the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans as they came and went.

William Smith, in his book, 'Morley Ancient and Modern', wrote the following about Iron production in the region: ".................. Cinderhill (in Morley), which derives its name from the numerous beds of cinders deposited here in former times. In the reign of the Plantagenets, and probably before then, there were many foundries in Morley and the neighbour hood. It is a striking fact connected with these foundries, that, though they were in many instances actually upon and but a few yards above beds of coal, the owners used timber more than anything else for their blast or smelting. One of these foundries was at the top of Neepshaw Lane, the place still being known as the "Stone Pits," thus bespeaking its origin, for the ore in this neighbourhood is still called "ironstone"; it is, therefore, probable that for brevity the old works or mines would be called the stone pits. That ironstone was meant is certain, for there was no stone suitable for building or road purposes in that locality. Scatcherd says: — "Before the woollen trade hereabouts became prevalent, the iron trade was carried on to a great extent nearly all around us. The Deightons, of Batley, were great ironfounders, and accumulated wealth."

Gildersome was fortunate to have all the necessary resources to make a smelting operation successful, iron ore, ample woodlands for charcoal making, water and easy access to the highroads. The word smelting is not entirely correct, rather it was an ancient process of converting iron ore to crude iron that could be hand worked but not pure enough to be poured into a mold. The process required a forge, called a bloomery, which was fueled by charcoal and fanned by human powered bellows. Numerous acres of woodland per year would have been consumed to make the charcoal necessary to break down the ore. Of course, this was dependant upon the number of bloomerys in operation and the crude iron tonnage produced. Obliviously a lot of woodland disappeared to keep the bloomeries in operation, if a smithy producing finished iron products occupied the site at the same time, more woodland would have vanished.

It's not known how long it took for the depletion of Gildersome's woodland, it could have been one hundred to three hundred years. The rate could have been, and probably was, offset by wise forest management. The Lord of the Manor probably employed one or more foresters who used their extensive knowledge of woodland management to nurture the dwindling resource. By the early 1500s, at the latest, most of Gildersome's woodlands were cleared and converted to farm and pasture land. Deeds from that century, concerning fields such as the Harthills, the Carrs, the Moor Closes and others, confirm that many of Gildersome's fields had been enclosed, indicating general agricultural use.

This theory postulates that the early interest in Gildersome centered around the top of Nepshaw Lane and its intersection with The Street. Starting from there the clearcutting expanded in a northward direction. It must be remembered that this theory is based upon the facts as they are known and what was generally happening in the region in the time, the real events may have been completely different.

England in the middle ages, was a wooden world. The market for wood and charcoal was insatiable and the demand kept on growing. Gildersome had what many other existing manors lacked, or had exhausted by the 12th century, easy access to an extensive and relatively untouched woodland. The commercial potential was sizeable, profits from the sale of timber and charcoal alone would have exceeded those of an established manor whose economy was entirely farm based. Thanks to a good road network and proximity to many nearby markets, including the river ports of Leeds and Wakefield, Gildersome's yield probably suffered from no lack of buyers, even when times were bad.

Gildersome's other economic asset was iron ore called ironstone, a sandstone, which was found over a large portion of West Yorkshire and mined extensively during the middle ages. Ironstone was apparently abundant and easily accessible near the top of Nepshaw Lane and Old Stone Pitts Road and along The Street's south side where the land fell away. It's highly likely that ironstone mining and a crude furnace, called a bloomery, could have have been in continuous operation for quite some time. If so, the distinctive stone pits and cinder mounds, left by the previous miners, would have been easily spotted and exploited by the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans as they came and went.

William Smith, in his book, 'Morley Ancient and Modern', wrote the following about Iron production in the region: ".................. Cinderhill (in Morley), which derives its name from the numerous beds of cinders deposited here in former times. In the reign of the Plantagenets, and probably before then, there were many foundries in Morley and the neighbour hood. It is a striking fact connected with these foundries, that, though they were in many instances actually upon and but a few yards above beds of coal, the owners used timber more than anything else for their blast or smelting. One of these foundries was at the top of Neepshaw Lane, the place still being known as the "Stone Pits," thus bespeaking its origin, for the ore in this neighbourhood is still called "ironstone"; it is, therefore, probable that for brevity the old works or mines would be called the stone pits. That ironstone was meant is certain, for there was no stone suitable for building or road purposes in that locality. Scatcherd says: — "Before the woollen trade hereabouts became prevalent, the iron trade was carried on to a great extent nearly all around us. The Deightons, of Batley, were great ironfounders, and accumulated wealth."

Gildersome was fortunate to have all the necessary resources to make a smelting operation successful, iron ore, ample woodlands for charcoal making, water and easy access to the highroads. The word smelting is not entirely correct, rather it was an ancient process of converting iron ore to crude iron that could be hand worked but not pure enough to be poured into a mold. The process required a forge, called a bloomery, which was fueled by charcoal and fanned by human powered bellows. Numerous acres of woodland per year would have been consumed to make the charcoal necessary to break down the ore. Of course, this was dependant upon the number of bloomerys in operation and the crude iron tonnage produced. Obliviously a lot of woodland disappeared to keep the bloomeries in operation, if a smithy producing finished iron products occupied the site at the same time, more woodland would have vanished.

It's not known how long it took for the depletion of Gildersome's woodland, it could have been one hundred to three hundred years. The rate could have been, and probably was, offset by wise forest management. The Lord of the Manor probably employed one or more foresters who used their extensive knowledge of woodland management to nurture the dwindling resource. By the early 1500s, at the latest, most of Gildersome's woodlands were cleared and converted to farm and pasture land. Deeds from that century, concerning fields such as the Harthills, the Carrs, the Moor Closes and others, confirm that many of Gildersome's fields had been enclosed, indicating general agricultural use.

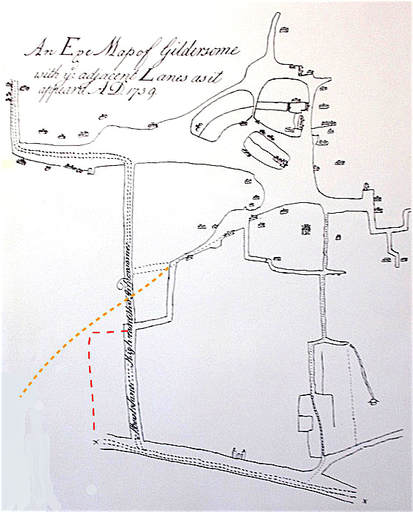

A purely representational map depicting the early development of Gildhus

Click on Map to Enlarge

Click on Map to Enlarge

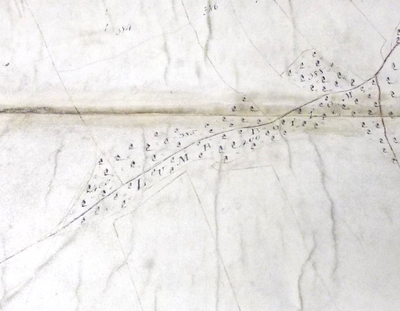

Upp Olde Stoney Pitts Roade?

As mentioned earlier, sometime around the early to middle 13th century Gildhus (Gildersome) officially came into existence. Along with the rights to the manor, the new Lord, whomever he was at that time, would also have been granted the privilege to mine the prime ironstone beds (#7 on the map above). Since we assume that mining and smelting were already taking place at the time of the new charter, the most logical place to begin the clearcutting and expansion was to the north of the mining area, beyond Lumb Bottom (#5 on the map above). A service road, later called Old Stone Pits Road, already ran through the middle of the open pit field, facilitating this northward push. Later, when the mining operation was no longer profitable the workings were transformed into agricultural fields which came to be known as The Old Stone Pitts, a name that has survived into the twentieth century. The Stone Pits remained in the possession of each successive Manorial Lord until they were sold by Lady Cardigan circa 1890.

As mentioned earlier, sometime around the early to middle 13th century Gildhus (Gildersome) officially came into existence. Along with the rights to the manor, the new Lord, whomever he was at that time, would also have been granted the privilege to mine the prime ironstone beds (#7 on the map above). Since we assume that mining and smelting were already taking place at the time of the new charter, the most logical place to begin the clearcutting and expansion was to the north of the mining area, beyond Lumb Bottom (#5 on the map above). A service road, later called Old Stone Pits Road, already ran through the middle of the open pit field, facilitating this northward push. Later, when the mining operation was no longer profitable the workings were transformed into agricultural fields which came to be known as The Old Stone Pitts, a name that has survived into the twentieth century. The Stone Pits remained in the possession of each successive Manorial Lord until they were sold by Lady Cardigan circa 1890.

|

The above 1852 map clearly shows Old Stone Pits fields, the Earl of Cardigan's property, and Stone Pits Lane which was part of the Lord's Waste and remained a road into Gildersome until recently when it became a public Footway (the orange shaded area). "Nibshaw" Lane is the dividing line between Gildersome and Morley. The blue shaded fields are the Lord of Dartmouth's property. The Stone Pitts are clearly demesne lands granted at the founding of the manor and handed down since the charter from lord to lord.

|

In this 18th century map, the turnpike road from Leeds to The Street goes straight from Morley to Bruntcliffe and Nipshaw Rd, though not shown, has become a convenient shortcut for those not needing the use of the turnpike. The two main entrances into Gildersome are Old Stone Pitts Road and Branch/Asquith avenues. Soon after, Street Lane was reconstructed as a turnpike allowing quicker access from The Street to Farnley.

|

|

In the beginning, it's more than likely that most trees around the new settlement of Gildhus and its' mining operation had been felled. So what would have been more natural than the deforestation to follow Stone Pitts Road north, fanning out in an arc from the west to east. The topography is relatively flat and would made good farm and grazing land. How long it took to reach the present Town Street and Branch Avenue is anyone's guess but eventually it did. Right: Old Stone Pitts Road Today, looking south from Gelderd Road. #4 in the above Map.

|

One hard to miss feature near the Stone Pitts is Lumb Botton (#6 in the 1200 to 1400 map above). In 'Old Yorkshire', edited by W. Wheater 1885 page 294, it states that: "Lum, Lumb. --- This name, with or without the b, which is a modern addition, is applied to a number of places, especially in the elevated districts of the West Riding of Yorkshire. where a brook or streamlet runs through a wooded gorge, and forms in its course pools of water more or less deep. (as in)...Near Drighlington are Lumb-Bottom, Lumb-Woodand Lumb-Hall." Lumb Bottom is the lower part of a stream which forked with Dean Beck and may have been called Lumb Beck (the 1800 Enclosure Map below, specifically designates 'Lumb Bottom' as an entity distinct from Dean Beck). This too may indicate that Drighlington's Lumb Wood once extended into Gildersome but just how far is anybody's guess. I believe that early in Gildersome's existence, Lumb Bottom would have been the perfect spot to create a reservoir. By damming the eastern end, it's quite possible that enough fall could have been generated to power a mill, either for grinding or to power a bellows. It's interesting that the Gildersome/Morley boundary line turns south and follows the Dean fork to Nepshaw Road, this allowed Gildersome access to Lumb Bottom and the Nepshaw intersection.

The 1852 map, above, shows Lumb Bottom circled in red and the location of Dean Bridge shown in blue. The location of the red circle in the Today's map, matches the location on the 1852 map. The yellow dashed line in the Today's map is the position of Old Stone Pitts and Old Coal Pit Lanes. Much of early Gildhus may have been centered around Lumb Bottom. An archaeological survey of the remaining fields surrounding the bottoms, before they're gone, might turn up some interesting finds. (TOO LATE! Written last year, since, the fields have been gouged and scraped and prepared for development)

Branch Avenue (#5 on the 1200 -1400 map above) was probably so named because it forked in two directions, one road led to Leeds and the other to Morley. These were ancient footways, hundreds of years old, used by hunters and herders to access the Hart Hill area. When the early clearcutting of Gildersome moved north past Lumb Bottom, the need for a shortcut to haul the felled trees to Morley and the Leeds Road became apparent. The old footway to Morley Hole was the oblivious choice. To accomplish that task, the path was improved and a bridge was built across Dean Beck, sturdy enough for loaded oxcarts (the lorries of their day) and high enough to withstand any flooding. Old maps reveal that such a bridge was located very close to the present one on Asquith Avenue. As Dean Bridge was slightly across Gildersome's boundary line, its repair became the responsibility of Morley and its condition, and ultimately its use, depended upon a good relationship between the two towns which could, and did, ebb and flow. With the coming of the turnpike system and the rise of the textile industry in the 18th century, the road to Morley Hole was unable to support the increasing heavy traffic and gradually it declined untill it again became a mere footway. It was not until the 1890s that a modern bridge and road was constructed, then called the New Bridge and the New Road (Asquith Avenue). It was open to traffic of all sorts and shortened the distance between Morley and Gildersome by over a mile.

|

This 1739 Map of Gildersome was made as a plan for a proposed Turnpike road which would run up Street Lane then left to Farnley. The orange line is the original course of Finkle Ln. The red line is a possible early piece of Finkle Lane which was abandoned with the coming of Street Lane. The proposed shortcut connection to Street Ln, indicated by the dark broken line, didn't happen until 1803. In the satellite view below, the orange line is the original "dog leg' shown above and the red corresponds to the red line. Also visible below are some of the original "strip" fields.

|

Proof of ancient Viking influence in Gildersome comes from the word Finkle. The name is derived from either Old Norse meaning elbow, bend or even dog-leg or the Old Danish word, vincle, which meant a corner or angle (in German the word winkle means corner). The name has survived in nearby towns such as Leeds, Selby, Knaresborough, Richmond, Thirsk and one was thought to have existed in York. It follows that most of local Finkle Streets will have a sharp corner or angle somewhere along their length, or perhaps they would have had such a feature in their early days.

Gildersome's Finkle Lane probably began its life as an ancient footpath that ran from The Street to the Town Green and may even have intersected with The Street as far west as Adwalton (see: #3 on the 1200 -1400 map above). When Gildersome's town centre shifted to near its present location, the footpath became a new entrance into town. It was then that the cleared land around the footpath was transformed into strips, long and narrow rectangles that trended in a north/south direction. In the middle ages, this communal field arrangement, called Strip Farming, was the custom. To accommodate the newly organised fields, the old footpath had to be diverted around the perimeter of those "strips" so as to not pass directly through. The only portion of the old footway that retained its original "angle" was at the Nook. I believe that it was then that the route became known as Finkle Lane. |

|

Manor and Mill Pond

Soon after the charter creating the Manor of Gildersome, a manor house would have been built to lodge the new Lord's overseer and a small staff of specialists. Their duty was to manage the manor, collect taxes, settle minor disputes, etc. The new Manor house would have been made of wood. Where it was situated is unknown but it probably sat somewhere near a good water source and upwind from the burning of stumps, charcoal and iron furnaces. If the manor's Lord ever visited Gildhus, he would have brought his entourage of guards, inspectors and friends. The inspectors would tour the manor while the Lord and his friends hunted Dean, Farnley or Lumb Woods. Gildhus, being too rustic, his Lordship would have quartered at the best house available in the vicinity, probably in Morley or Drig. |

After 400 years or so, who knows how many different manor houses were built, and where. Finally, a manor house was built of stone which endured until the 1950s (#1 on the 1200 -1400 map above). Situated on Harthill Lane, it was probably built during the Tudor period (1500s). It was a two story dwelling with a thatched roof and most likely received several rebuilds during its lifetime. Sometime in the latter part of the 19th century, its top story was removed. Surrounding the manor house were fields designated as support for the Lord's reeve (overseer), better known as the Lord's demesne. these were sold by Lady Cardigan in the early 1900s. I believe that an overseer continuously occupied the manor until the late 1700s after which the property was put out to let. Below the manor house was a pinfold where were kept strays or livestock seized for back taxes or rent.

Across today's Spring View from the manor house was the location of a dammed up pond that serviced a mill, probably to grind corn. The pond existed for hundreds of years and was still in use in textile production right into the 1950s, when it was filled in.

Across today's Spring View from the manor house was the location of a dammed up pond that serviced a mill, probably to grind corn. The pond existed for hundreds of years and was still in use in textile production right into the 1950s, when it was filled in.

|

The diagram on the left depicts a typical medieval manor. In many ways, it's very similar to how Gildersome must have looked once it was cleared and fields were established. Strip cropping was a method of partitioning fields into long narrow strips. This practice was quite common during the middle ages. Some of these "strip" fields can still be found in Gildersome today, such as near Scott Green.

Click on graphic to expand. |

|

When Gildersome's best land was cleared of trees and the fires in the forges were extinguished for good, the stone pits were filled in to make way for additional farmland. Gildersome settled down and became a bucolic hamlet, probably dependent upon the nearby townships as the primary market for its agricultural surpluses. As the centuries came and went, there was little change. That is until the mid 18th century when the coming of the industrial revolution intruded upon its traditional way of life. |

Gildersome in Medieval Records:

Below is a list of 25 records or references for which I'm certain are about our Gildersome. All, I've pulled off the internet. I have many more for the place name Gildhus, or its variants, but they are from other parts of Yorkshire or other counties. I also have many references to people bearing the name Gildhus, or its variants, but again I'm not sure of a connection. For example, in Lancashire there's a 1421 reference to an Elizabeth Gildhus at Lyndyate. And, I've held back many definite 16th century records for the sake of brevity.

1176-1177:

The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Thirty Third year of the reign of King Henry II Vol. 26 Pg 79 :

"Idem vicecomes reddit compotum de catallis fugitivorum et eorum qui perierunt judicio aque per assisam de norhanton de anno preterito. Quorum nomina subscribuntur. ................. De Radulfo del Gildhus . xxi. s. ...........

In thesauro liberavit. Et quietus est."

Possible translation above.

1181:

The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Twenty seventh year of the reign of King Henry II Vol. 30 Pg 44 :

De oblatis Curie.

Idem vicecomes redd. comp. de .vj. s. et .viij. d. de Rogero de Gildehusum. Et de dim. m. de Alwin de Horton’ quia retraxerunt se de appellatione sua. In thesauro liberavit in ij. talliis.

Et quietus est.

Possible translation above.

1226

Feet of Fines, Yorkshire, II Hen. III., No. 58. "Between Nicholas de Rithereffeld and Eufemia his wife, plaintiffs, and Marmaduke Darel and Helewisa his wife, tenants, of half all the lands which belonged to William de Insula, father of Eufemia and Helewisa, in Broddeswrth, Quendal, Sutton, Morle, Neweton, Beston, Cottingle, Cherlewell, Hansee, Puntfreit, Eusthorp, Dritlington, Gildhus, Poles, Pikeburn, Bukethorp, Squalecroft, and Finchden. Nicholas and Eufemia to have all the lands in Quendal, Sutton, Morle, Neweton, Puntfreit, Eusthorp, Beston, Cottingle, Cherlewell, Dritlington, Gildhus, Fincheden, Squalecroft, Poles, and Hansee, except the homage and service of Hugo de Langetweit of the land of Diglandes.

Marmaduke and Helewisa to have all the rest, i.e., Broddeswrth with the advowson, Pikeburn, Buggethorp, and the aforesaid service of Hugo de Langetweit."

1233

West Yorkshire: Archaeological an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, page 268 : ......Farnley Wood Beck, separating Drighlington, Gildersome and Churwell. The stream is mentioned in a dispute settled c. 1233 defining the boundaries between the parishes of Leeds and Batley, and more precisely, in which of the two parishes Churwell lay. The agreed boundary lay in part along 'a certain stream (rivus) descending between the wood (nemus) of Feanley and the assart of Gildersome', the incomplete summary clause stating that the boundary ran 'starting from the stream between Farnley and Gildersome'. The same boundary is refered to in a quitclaim of the period 1246-58 releasing the land in Farnley in various parcels............." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view. I have ordered the book and hope to have the full paragraph as well as others soon)

Sometime in the 1200s (date still to be determined) :

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series Vol. 62, Page 30, No. 125 : "......Between William son of Samson, Agnes his wife and Alice sister of Agnes, claiments, and Roger of Gildhusun, tenant: as to a bovate of land in Erdeslawe (Ardsley). Quitclaim by William. Agnes and Alice, for themselves and the heirs of Agnes and Alice, to Roger and his heirs. Roger gives 5 shillings sterling." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1249

Yorkshire Inquisitions XVII : "Alexander de Nevill. Inq. p.m. [33 Hen. III No. 50] Writ fated at Westminster, 12 July, 33 rd year. Inquisition made by Nicholas de Erdeslawe, John of the same, John de Batelay, Hugh de Muhaut, Nicholas de Mirefeld, John de Alta Ripa, thomas de heden, john del Hil', Sampson de Gilhusum, Robert son of Richard of Mirfeud, Alexander of the same, Roger Alayn, and John de Birstal, who say that Alexander de Nevill had in Nunington two carucates and two bovates of land in demesne, which he held of the Abbot of S. Mary's, York......"

1268 :

Grant of a bovate of land in Headingley by William de Gildhus

"Scaint omnes presentes et futuri quod ego Willelmus de Gildhus, pro amore Dei et salute anime mee, heredum et antecessorum meorum, per bonam uoluntatem et gratum Matildis vxoris mee, dedi et concessi et hac mea carta confirmaui Deo et Sancte Marie et monachis de Kirk[stall] inperpetuum unam bouatam terre in Eaddingla', cum omnibus pertinentiis suis ubique, sine aliquo retinemento: tenendam de me et de heredibus meis in perpetuam elemosinam: reddendo annuatim mihi et heredibus meis x denarios pro omni seruicio quod ad me uel ad heredes meos pertinet, videlicet v denarios ad festum Sancti Martini et v denarios ad Pentecosten. Et monachi facient forense seruicium quantum pertinet ad unam dimidiam bouatam, unde octo carrucate faciunt feodum militis. Ego uero et heredes mei warrantizabimus et adquietabimus et defendemus predictam terram prenominatis monachis vbique et erga omnes homines. Testes."

This grant was confirmed by William's uncle, Thomas Peitevin.

Translation: All present and future that I, William de Gildhus, for the love of God and the salvation of the of my soul, of my ancestors and heirs, by means of a good and agreeable to the will of my wife, Maud, I have given and granted and by this my charter confirmed to God and St. Mary and the monks of the Kirk [stall] for ever, one bovate of land in Headingley', with all its appurtenances, without any reserve, to be held in perpetual alms of me and my heirs: the heirs of an annual payment to me, and all my money in lieu of the service which 10 denari belongs to me or to my heirs, that is to say 5 pence at the feast of St Martin, and Pentecost. And as much as it belongs to the one half of the service of the monks they will do a forensic Bouata, from which eight carrucate make a knight 's fee. I am, however, and my heirs, will warrant, acquit and defend the aforesaid land to the aforesaid monks, and in all places and for all men. Witnesses

1280

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, 1956. Y.A.S.Record Series, vol. CXXI : "28.York. Morrow of Hil. 8 Edw I. Before the same. Between John, son of Robert de Ros of Hamelak, quer., and William de Rither, deforc., of the manors of Rither, Schardecroft, Gyldhusum' and the advowson of Rither church. Covenant. John's right as of William's gift. John and his heirs to hold of the chief lords. William and his heirs to warrant. For a sore sparrowhawk."

" 54. York. Morrow of Cand. Before the same. Between William de Ryther, quer., and John de Ros, deforc., of the manors of Ryther, Scarthecroft and Gildehus' with the advowson of Ryther church. Covenant. John's right. William and Lucy his wife and the heirs of Lucy's body to hold of the chief lords with remainder to William and reversion after William's death to John and the heirs of his body with remainders to Alexander, John's brother, and the heirs of his body and to William's next heirs. "

1298

Victoria County History, Vol. I., page 440, “Wakefield School.” : “A school at Wakefield existed as early as the 13th century as the following entry from the Court Roll of the Manor of Wakefield for 1298 clearly proves :-‘Alice, daughter of Henry Sampson of Gildusme (Gildersome) broke into the barn of Master John, rector of the School of Wakefield, at Topcliff, and stole 16 fleeces. She is to be arrested."

1300 - 1314

Feet of Fines for the County of York: From 1300 to 1314 - Page 23: "Adam son of Hugh de Gildesum, quer., and John de Brom and Agnes his wife, imped., of a toft, 10 acres of land and a rent of 6d. in Driglynton. Warranty of charter. Adam's right as of the gift of John and Agnes. He and his heirs to hold of the ......" (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1304

Calendar of the Charter Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward I - Edward II AD 1300 - 1326 Vol III 6 Mar 1304 : "Grant to William de Rythre, and his heirs, of free warren in all their demesne lands in Scarthecroft, Hornyton and Gyldusum , co. York."

1315

Court Rolls for the Manor of Wakefield Edward II : "Bailiff - Hugh de Gildesome and Amabilla, his wife, 6d, for withdrawing their suit against Alice del Wro in a plea of trespass. William de Gildesom, surety for the prosecution, and Hugh and Ambilla are amerced."

1323

Yorkshire Deeds Volume 9 : "Grant by Edmond de Nevyll to Richard Samson of Farnelay.................Witnesses: Sir William de Beeston, knt., William de Wyrkelay, Adam, the clerk of Gyldosum, ................."

1351

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series Vol. 93, Page 41 : "3 June 1351 Ingland, John, de, Gildesham, adm:...." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1352 - 1362

Yorkshire Deeds: - Volume 8 - Pages 167 thru 169 : A certain 'William de Gildoshome' is witness to four deeds concerning land in 'Wouelay' (Woolley).

1360 - 1370

The Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Journal, Volume 8, Page 28 : "Sir Rob. de Swillington the uncle gives to Sir Wm. de Fincheden and his heirs his manor of Slaghthwayte; No. 7, and acknowledges it to be his by Fine, No. 15; No. 28 and 29 are their warrants of atty. to give and receive, and on Monday in Easter week, 48 Edw. Il.I., Sir Wm. de Fynchedcu gave this manor with the manor of Woodsome and Farnley Tyas and other lands to Sir Robert de Swillington the uncle and Sir Wm. Mirfield, Knts. Sir Wm. Mirfielil parson of Bradford, Sir Ralph Hancock parson of Thurnscoc, Hugh Wombwell, John son of John Amyas, Wm. de Gildersome, and Richard Bulter; N o. 87, they paying yearly to the said donor 200 marks for life. 49 Edw. llI., the above William de Gildersome gives to Robt. de Maunton, Vicar of Eccles, and John Cupper, chaplain, his manor of Slaithwaite with the reversion of the dower of Alice, who was wife of William de Fyncheden, and the reversion of the manor of Woodsome and Farnley Tyas, which the said Alice held for the term of her life."

1392

Papers related to a land grant at The National Archives, Kew, C143/415/33: "Thomas de Woolay, chaplain, to grant messuages, land, and rent in Ardsley, Darfield, Wombwell, Wrangbrook, Skelbrooke, Gildersome and Wath to the prior and convent of Monk Bretton, York."

1401-1402

Inquisitions and assessments relating to feudal aids, with other analogous documents preserved in the Public record office; A.D. 1284-1431; published by authority of H.M. principal secretary of state for the Home department (Volume 6) : "De domino Willelmo de Ryther pro j. f. in Ryther et Gyldesone xx.s."

1404

Yorkshire Deeds 228. Nov 28, Henry IV : " Indenture by which John Daunay demises to Richard Gildersome and Thomas Lowe of Goldale all arable land and pasture which Simon de Hek lately held by by the law of England in the village of Goldale....."

1414 - 1420

Yorkshire Deeds Vol. IX, Page 91 : Concerning the previous "Richard Gildersome" and three transfers of property in Goldale.

1435

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal - Volume 12 - Page 48 : "Fines XXX [voL 106] 30 Between Oliuer Furbishour, Chaplaine, and John Lake of Wakefield, compl‘ and John Oliuer of Cayteby, Agnes his wife and Alice Berlou of Wakefield deforce of 6 messauges, 261 acres and 1 rood of Land, 12 Acres of medow, 20 Acres of pasture, 4 Acres of wood, and 3s 4d rent, with the appurtnances in Wakefield, Stanley, Snaypthorp, Robertthorp, Osset, Pountfreit, Preston Jakelin, Batelay, Bristall, Gildersham, Drightlington, and Chekynley. the right of Oliuer and John and their heires, foreuer."

1461

Testamenta Eboracensia: A Selection of Wills from the Registry at York, Volume 30 : " Testamentum Oliveri Myrfeld Armigeri ..........First I wille that my feffis that air enfeffed in al my lordschippes - in the townes of Mirfeld, Dighton, Egerton, Gleydholte, Heyton, hopton, Batley, Holey, Morley, Gildosome, Bolton, Chekylay, Leede, Newstede, Halyfax, Wakefelde, Westerton, with al theire appurtenaunces, make a state of theim - to William Mirfeld my son and to his eyeres of his body......"

1577

In Barnard’s Survey, under date August 23rd, 1577, reference is made to the “ Hamlet of Gildersom.”

1583

Deed of exchange of land in Gildersome, Transcript of the Popeley Document of 1583:

"This indenture made the xviith day of June in the xxvth yere of the Reygne of oure soverygne Ladie Elizabeth by the grace of god queen of ynglande france & yreland defender of the faith etc Bytwixt Robert popeley of popeley in the Countie of yorke gent of that one partie and Robert appleyerde & George appleyerd of Gildsum in the sayde Countie of that other partie wytnessth that the sayde Robert popeley hath gyvyn granntid & confirmed to the sayde Robert & George appleyerd his two lands of meddo in the yng lete of gildsome aforesayde as they lye nowe at the east syde by the lands of the sayde Robert Appleyerde [& George Appleyerde] in the northen syde of the sayde yng lete nere unto the same these late made by Rodger Strynger To have & to houlde the sayde two lands to the sayde Robert appleyerd & George appleyerd & to theyre heyre[e]s & assiynes of the sayde George for evr in exchange for theyse two lands hereafter gyvyn to the sayde Robert popeley and in like maner the sayde Robert Appleyerde & George Appleyerde have gyvyn granntid & confirmed unto the sayde Robert Popeley theyre two lands of meddo in the sayde yng lete & they now lye theyre at the west syde of lower lands of the sayde Robert Popeley in or about the mydst of the sayde yng lete. To have and to houlde the sayde two lands in or about the mydst of the sayde yng lete to the sayde Robert Popeley his heyres & assynes for evr in exchange for the sayde two lands heretofore gyvyn by the sayde Robert Popeley to the sayde Robert Appleyerde & George in wytness whereof the parties beforesaid to the parties of these indentures interchangably have set theyre sealls given the day & yere of the above wrytten.

syned Robert X Robert syned X 1583"

Below is a list of 25 records or references for which I'm certain are about our Gildersome. All, I've pulled off the internet. I have many more for the place name Gildhus, or its variants, but they are from other parts of Yorkshire or other counties. I also have many references to people bearing the name Gildhus, or its variants, but again I'm not sure of a connection. For example, in Lancashire there's a 1421 reference to an Elizabeth Gildhus at Lyndyate. And, I've held back many definite 16th century records for the sake of brevity.

1176-1177:

The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Thirty Third year of the reign of King Henry II Vol. 26 Pg 79 :

"Idem vicecomes reddit compotum de catallis fugitivorum et eorum qui perierunt judicio aque per assisam de norhanton de anno preterito. Quorum nomina subscribuntur. ................. De Radulfo del Gildhus . xxi. s. ...........

In thesauro liberavit. Et quietus est."

Possible translation above.

1181:

The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Twenty seventh year of the reign of King Henry II Vol. 30 Pg 44 :

De oblatis Curie.

Idem vicecomes redd. comp. de .vj. s. et .viij. d. de Rogero de Gildehusum. Et de dim. m. de Alwin de Horton’ quia retraxerunt se de appellatione sua. In thesauro liberavit in ij. talliis.

Et quietus est.

Possible translation above.

1226

Feet of Fines, Yorkshire, II Hen. III., No. 58. "Between Nicholas de Rithereffeld and Eufemia his wife, plaintiffs, and Marmaduke Darel and Helewisa his wife, tenants, of half all the lands which belonged to William de Insula, father of Eufemia and Helewisa, in Broddeswrth, Quendal, Sutton, Morle, Neweton, Beston, Cottingle, Cherlewell, Hansee, Puntfreit, Eusthorp, Dritlington, Gildhus, Poles, Pikeburn, Bukethorp, Squalecroft, and Finchden. Nicholas and Eufemia to have all the lands in Quendal, Sutton, Morle, Neweton, Puntfreit, Eusthorp, Beston, Cottingle, Cherlewell, Dritlington, Gildhus, Fincheden, Squalecroft, Poles, and Hansee, except the homage and service of Hugo de Langetweit of the land of Diglandes.

Marmaduke and Helewisa to have all the rest, i.e., Broddeswrth with the advowson, Pikeburn, Buggethorp, and the aforesaid service of Hugo de Langetweit."

1233

West Yorkshire: Archaeological an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, page 268 : ......Farnley Wood Beck, separating Drighlington, Gildersome and Churwell. The stream is mentioned in a dispute settled c. 1233 defining the boundaries between the parishes of Leeds and Batley, and more precisely, in which of the two parishes Churwell lay. The agreed boundary lay in part along 'a certain stream (rivus) descending between the wood (nemus) of Feanley and the assart of Gildersome', the incomplete summary clause stating that the boundary ran 'starting from the stream between Farnley and Gildersome'. The same boundary is refered to in a quitclaim of the period 1246-58 releasing the land in Farnley in various parcels............." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view. I have ordered the book and hope to have the full paragraph as well as others soon)

Sometime in the 1200s (date still to be determined) :

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series Vol. 62, Page 30, No. 125 : "......Between William son of Samson, Agnes his wife and Alice sister of Agnes, claiments, and Roger of Gildhusun, tenant: as to a bovate of land in Erdeslawe (Ardsley). Quitclaim by William. Agnes and Alice, for themselves and the heirs of Agnes and Alice, to Roger and his heirs. Roger gives 5 shillings sterling." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1249

Yorkshire Inquisitions XVII : "Alexander de Nevill. Inq. p.m. [33 Hen. III No. 50] Writ fated at Westminster, 12 July, 33 rd year. Inquisition made by Nicholas de Erdeslawe, John of the same, John de Batelay, Hugh de Muhaut, Nicholas de Mirefeld, John de Alta Ripa, thomas de heden, john del Hil', Sampson de Gilhusum, Robert son of Richard of Mirfeud, Alexander of the same, Roger Alayn, and John de Birstal, who say that Alexander de Nevill had in Nunington two carucates and two bovates of land in demesne, which he held of the Abbot of S. Mary's, York......"

1268 :

Grant of a bovate of land in Headingley by William de Gildhus

"Scaint omnes presentes et futuri quod ego Willelmus de Gildhus, pro amore Dei et salute anime mee, heredum et antecessorum meorum, per bonam uoluntatem et gratum Matildis vxoris mee, dedi et concessi et hac mea carta confirmaui Deo et Sancte Marie et monachis de Kirk[stall] inperpetuum unam bouatam terre in Eaddingla', cum omnibus pertinentiis suis ubique, sine aliquo retinemento: tenendam de me et de heredibus meis in perpetuam elemosinam: reddendo annuatim mihi et heredibus meis x denarios pro omni seruicio quod ad me uel ad heredes meos pertinet, videlicet v denarios ad festum Sancti Martini et v denarios ad Pentecosten. Et monachi facient forense seruicium quantum pertinet ad unam dimidiam bouatam, unde octo carrucate faciunt feodum militis. Ego uero et heredes mei warrantizabimus et adquietabimus et defendemus predictam terram prenominatis monachis vbique et erga omnes homines. Testes."

This grant was confirmed by William's uncle, Thomas Peitevin.

Translation: All present and future that I, William de Gildhus, for the love of God and the salvation of the of my soul, of my ancestors and heirs, by means of a good and agreeable to the will of my wife, Maud, I have given and granted and by this my charter confirmed to God and St. Mary and the monks of the Kirk [stall] for ever, one bovate of land in Headingley', with all its appurtenances, without any reserve, to be held in perpetual alms of me and my heirs: the heirs of an annual payment to me, and all my money in lieu of the service which 10 denari belongs to me or to my heirs, that is to say 5 pence at the feast of St Martin, and Pentecost. And as much as it belongs to the one half of the service of the monks they will do a forensic Bouata, from which eight carrucate make a knight 's fee. I am, however, and my heirs, will warrant, acquit and defend the aforesaid land to the aforesaid monks, and in all places and for all men. Witnesses

1280

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, 1956. Y.A.S.Record Series, vol. CXXI : "28.York. Morrow of Hil. 8 Edw I. Before the same. Between John, son of Robert de Ros of Hamelak, quer., and William de Rither, deforc., of the manors of Rither, Schardecroft, Gyldhusum' and the advowson of Rither church. Covenant. John's right as of William's gift. John and his heirs to hold of the chief lords. William and his heirs to warrant. For a sore sparrowhawk."

" 54. York. Morrow of Cand. Before the same. Between William de Ryther, quer., and John de Ros, deforc., of the manors of Ryther, Scarthecroft and Gildehus' with the advowson of Ryther church. Covenant. John's right. William and Lucy his wife and the heirs of Lucy's body to hold of the chief lords with remainder to William and reversion after William's death to John and the heirs of his body with remainders to Alexander, John's brother, and the heirs of his body and to William's next heirs. "

1298

Victoria County History, Vol. I., page 440, “Wakefield School.” : “A school at Wakefield existed as early as the 13th century as the following entry from the Court Roll of the Manor of Wakefield for 1298 clearly proves :-‘Alice, daughter of Henry Sampson of Gildusme (Gildersome) broke into the barn of Master John, rector of the School of Wakefield, at Topcliff, and stole 16 fleeces. She is to be arrested."

1300 - 1314

Feet of Fines for the County of York: From 1300 to 1314 - Page 23: "Adam son of Hugh de Gildesum, quer., and John de Brom and Agnes his wife, imped., of a toft, 10 acres of land and a rent of 6d. in Driglynton. Warranty of charter. Adam's right as of the gift of John and Agnes. He and his heirs to hold of the ......" (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1304

Calendar of the Charter Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward I - Edward II AD 1300 - 1326 Vol III 6 Mar 1304 : "Grant to William de Rythre, and his heirs, of free warren in all their demesne lands in Scarthecroft, Hornyton and Gyldusum , co. York."

1315

Court Rolls for the Manor of Wakefield Edward II : "Bailiff - Hugh de Gildesome and Amabilla, his wife, 6d, for withdrawing their suit against Alice del Wro in a plea of trespass. William de Gildesom, surety for the prosecution, and Hugh and Ambilla are amerced."

1323

Yorkshire Deeds Volume 9 : "Grant by Edmond de Nevyll to Richard Samson of Farnelay.................Witnesses: Sir William de Beeston, knt., William de Wyrkelay, Adam, the clerk of Gyldosum, ................."

1351

Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series Vol. 93, Page 41 : "3 June 1351 Ingland, John, de, Gildesham, adm:...." (Taken from a Google search book snippet view.)

1352 - 1362

Yorkshire Deeds: - Volume 8 - Pages 167 thru 169 : A certain 'William de Gildoshome' is witness to four deeds concerning land in 'Wouelay' (Woolley).

1360 - 1370

The Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Journal, Volume 8, Page 28 : "Sir Rob. de Swillington the uncle gives to Sir Wm. de Fincheden and his heirs his manor of Slaghthwayte; No. 7, and acknowledges it to be his by Fine, No. 15; No. 28 and 29 are their warrants of atty. to give and receive, and on Monday in Easter week, 48 Edw. Il.I., Sir Wm. de Fynchedcu gave this manor with the manor of Woodsome and Farnley Tyas and other lands to Sir Robert de Swillington the uncle and Sir Wm. Mirfield, Knts. Sir Wm. Mirfielil parson of Bradford, Sir Ralph Hancock parson of Thurnscoc, Hugh Wombwell, John son of John Amyas, Wm. de Gildersome, and Richard Bulter; N o. 87, they paying yearly to the said donor 200 marks for life. 49 Edw. llI., the above William de Gildersome gives to Robt. de Maunton, Vicar of Eccles, and John Cupper, chaplain, his manor of Slaithwaite with the reversion of the dower of Alice, who was wife of William de Fyncheden, and the reversion of the manor of Woodsome and Farnley Tyas, which the said Alice held for the term of her life."

1392

Papers related to a land grant at The National Archives, Kew, C143/415/33: "Thomas de Woolay, chaplain, to grant messuages, land, and rent in Ardsley, Darfield, Wombwell, Wrangbrook, Skelbrooke, Gildersome and Wath to the prior and convent of Monk Bretton, York."

1401-1402

Inquisitions and assessments relating to feudal aids, with other analogous documents preserved in the Public record office; A.D. 1284-1431; published by authority of H.M. principal secretary of state for the Home department (Volume 6) : "De domino Willelmo de Ryther pro j. f. in Ryther et Gyldesone xx.s."

1404

Yorkshire Deeds 228. Nov 28, Henry IV : " Indenture by which John Daunay demises to Richard Gildersome and Thomas Lowe of Goldale all arable land and pasture which Simon de Hek lately held by by the law of England in the village of Goldale....."

1414 - 1420

Yorkshire Deeds Vol. IX, Page 91 : Concerning the previous "Richard Gildersome" and three transfers of property in Goldale.

1435

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal - Volume 12 - Page 48 : "Fines XXX [voL 106] 30 Between Oliuer Furbishour, Chaplaine, and John Lake of Wakefield, compl‘ and John Oliuer of Cayteby, Agnes his wife and Alice Berlou of Wakefield deforce of 6 messauges, 261 acres and 1 rood of Land, 12 Acres of medow, 20 Acres of pasture, 4 Acres of wood, and 3s 4d rent, with the appurtnances in Wakefield, Stanley, Snaypthorp, Robertthorp, Osset, Pountfreit, Preston Jakelin, Batelay, Bristall, Gildersham, Drightlington, and Chekynley. the right of Oliuer and John and their heires, foreuer."

1461

Testamenta Eboracensia: A Selection of Wills from the Registry at York, Volume 30 : " Testamentum Oliveri Myrfeld Armigeri ..........First I wille that my feffis that air enfeffed in al my lordschippes - in the townes of Mirfeld, Dighton, Egerton, Gleydholte, Heyton, hopton, Batley, Holey, Morley, Gildosome, Bolton, Chekylay, Leede, Newstede, Halyfax, Wakefelde, Westerton, with al theire appurtenaunces, make a state of theim - to William Mirfeld my son and to his eyeres of his body......"

1577

In Barnard’s Survey, under date August 23rd, 1577, reference is made to the “ Hamlet of Gildersom.”

1583

Deed of exchange of land in Gildersome, Transcript of the Popeley Document of 1583:

"This indenture made the xviith day of June in the xxvth yere of the Reygne of oure soverygne Ladie Elizabeth by the grace of god queen of ynglande france & yreland defender of the faith etc Bytwixt Robert popeley of popeley in the Countie of yorke gent of that one partie and Robert appleyerde & George appleyerd of Gildsum in the sayde Countie of that other partie wytnessth that the sayde Robert popeley hath gyvyn granntid & confirmed to the sayde Robert & George appleyerd his two lands of meddo in the yng lete of gildsome aforesayde as they lye nowe at the east syde by the lands of the sayde Robert Appleyerde [& George Appleyerde] in the northen syde of the sayde yng lete nere unto the same these late made by Rodger Strynger To have & to houlde the sayde two lands to the sayde Robert appleyerd & George appleyerd & to theyre heyre[e]s & assiynes of the sayde George for evr in exchange for theyse two lands hereafter gyvyn to the sayde Robert popeley and in like maner the sayde Robert Appleyerde & George Appleyerde have gyvyn granntid & confirmed unto the sayde Robert Popeley theyre two lands of meddo in the sayde yng lete & they now lye theyre at the west syde of lower lands of the sayde Robert Popeley in or about the mydst of the sayde yng lete. To have and to houlde the sayde two lands in or about the mydst of the sayde yng lete to the sayde Robert Popeley his heyres & assynes for evr in exchange for the sayde two lands heretofore gyvyn by the sayde Robert Popeley to the sayde Robert Appleyerde & George in wytness whereof the parties beforesaid to the parties of these indentures interchangably have set theyre sealls given the day & yere of the above wrytten.

syned Robert X Robert syned X 1583"