|

⬆︎ Use pull down menus above to navigate the site.

|

|

What you didn’t know about the Old Hall: the Luddite attack, Gildersome’s connection with the Peterloo Massacre, and the man who buried his wife in a field.

by: Andrew Bedford © 2019

by: Andrew Bedford © 2019

Published in May 1812 by Messrs. Walker and Knight, Sweetings Alley, Royal Exchange

Published in May 1812 by Messrs. Walker and Knight, Sweetings Alley, Royal Exchange

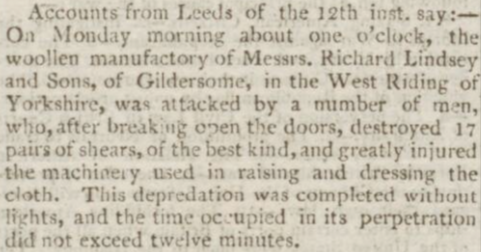

In the early hours of Monday the third of September 1812, the woollen manufactory of Messrs Richard Lindsey and Sons, Old Hall, Gildersome, was attacked. In a raid lasting little more than twelve minutes, seventeen shearing frames were destroyed and the machinery used for raising and dressing the cloth was ‘greatly injured.’1 The attack on Lindsey’s Mill is reputed to be one of the final acts of aggression perpetrated by the Luddites and survives as little more than a footnote to the history of Luddism in West Yorkshire. This article is an attempt to restore this barely remembered episode, along with some of the characters involved, to a position of prominence in the history of Gildersome.

In 1812, Gildersome’s economy was largely driven by the manufacture of woollen cloth. A downturn in demand for woollen products at the time of the Napoleonic wars resulted in legislation protecting the practices of skilled hand workers being repealed (1809). This enabled entrepreneurial opportunities to develop labour saving machinery that could drastically reduce manufacturing costs, thereby (or so it was hoped) giving UK manufacturers an economic advantage in a dwindling global marketplace. Lindsey and Sons was a business that embraced this innovation. The shearing frames set up in the mill premises at Gildersome’s Old Hall were able to finish cloth in a fraction of the time taken by traditional methods.

Lady Ludd (above) made her appearance on the 18th of August, 1812, in Briggate, Leeds, leading a crowd of people protesting about the high price of corn. The rioters progressed to Holbeck, where the premises of one Mr Shackleton, a miller, were badly damaged.

Before the shearing frame had been invented, the process for finishing woollen cloth had been a lengthy and labour-intensive process. The cloth had to be stretched on tenter frames and brushed with teazles. This raised the nap of the cloth, which was then smoothed by skilled craftsmen (croppers) using heavy metal shears. Dependent on the quality of finish required, the cloth may go through the same process several more times before it was ready for market. It becomes evident, then, that the introduction of shearing frames would have been especially problematic for those operatives who made their living by finishing cloth by hand.

Hand cropping, or shearing, was a specialised and arduous task performed by workers who understood the value of their labour. In 1802 Earl Fitzwilliam, Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, described the croppers as ‘the tyrants of the country’ whose ‘power and influence has grown out of their high wages’.2 As early as 1799 a Home Office investigation into union activities had identified a marked correspondence between the activities of the Yorkshire cloth-finishers and the destruction of gig mills.3 (Gig mills were simple machines for raising the nap of the cloth by passing it over teazles.)

In the early 1800s cloth manufacture was very much a cottage industry. As late as 1838 it was estimated that there were still around 120 handloom weavers operating in Gildersome.4 A family chronicle, written some fifty years after the events described, provides a valuable insight into the local situation at the time:

In 1812, Gildersome’s economy was largely driven by the manufacture of woollen cloth. A downturn in demand for woollen products at the time of the Napoleonic wars resulted in legislation protecting the practices of skilled hand workers being repealed (1809). This enabled entrepreneurial opportunities to develop labour saving machinery that could drastically reduce manufacturing costs, thereby (or so it was hoped) giving UK manufacturers an economic advantage in a dwindling global marketplace. Lindsey and Sons was a business that embraced this innovation. The shearing frames set up in the mill premises at Gildersome’s Old Hall were able to finish cloth in a fraction of the time taken by traditional methods.

Lady Ludd (above) made her appearance on the 18th of August, 1812, in Briggate, Leeds, leading a crowd of people protesting about the high price of corn. The rioters progressed to Holbeck, where the premises of one Mr Shackleton, a miller, were badly damaged.

Before the shearing frame had been invented, the process for finishing woollen cloth had been a lengthy and labour-intensive process. The cloth had to be stretched on tenter frames and brushed with teazles. This raised the nap of the cloth, which was then smoothed by skilled craftsmen (croppers) using heavy metal shears. Dependent on the quality of finish required, the cloth may go through the same process several more times before it was ready for market. It becomes evident, then, that the introduction of shearing frames would have been especially problematic for those operatives who made their living by finishing cloth by hand.

Hand cropping, or shearing, was a specialised and arduous task performed by workers who understood the value of their labour. In 1802 Earl Fitzwilliam, Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, described the croppers as ‘the tyrants of the country’ whose ‘power and influence has grown out of their high wages’.2 As early as 1799 a Home Office investigation into union activities had identified a marked correspondence between the activities of the Yorkshire cloth-finishers and the destruction of gig mills.3 (Gig mills were simple machines for raising the nap of the cloth by passing it over teazles.)

In the early 1800s cloth manufacture was very much a cottage industry. As late as 1838 it was estimated that there were still around 120 handloom weavers operating in Gildersome.4 A family chronicle, written some fifty years after the events described, provides a valuable insight into the local situation at the time:

In October 1811 Samuel the youngest son of James and Martha Bilbrough came of age. Since he left school he had worked at the loom which stood in the old house [Harthill House]. The family at home consisted of his mother and two sisters, with his brother John and himself. Amongst manufacturers at this time, things were very unsettled, and even in Gildersome where many looms were worked in private houses, men walked round at a certain hour in the evening, and stones were thrown through windows as a warning to stop work and sometimes they heard shouts to put out the light, “the rioters were coming”. They kept guns ready loaded to defend themselves if necessary.5

As well as providing a fascinating account from the manufacturers’ perspective, the document suggests that the grievances of the “rioters” were not exclusively focused on the larger manufacturers; that those operating hand looms in private houses found themselves under threat for working late reveals a wider picture in which cloth production was outstripping demand, with inevitable consequences for everyone involved in the process. It also appears to suggest that what became known as the “Luddite” disturbances were not entirely attributable to the croppers and certainly not to the seventeen unfortunates that would be hanged at York Castle in 1813.

|

This report from the Hereford Journal (1812) reveals that the attack on Lindsey’s mill received nationwide coverage. That the raid lasted less than 12 minutes and in darkness also indicates that the perpetrators may have had some familiarity with their target. It might be suggested, therefore, that at least some of the perpetrators may have been Gildersome men.

|

On September 13th 1812, a Special General Sessions of the Justices of the Peace for the West Riding of Yorkshire identified Gildersome, along with neighbouring townships including Liversedge, Heckmondwike, Batley and Morley, as places in which ‘disturbances prevail or are apprehended.’6 To this end those townships were ordered to ensure that every male ratepayer ‘shall be liable to the duties of watching by night, and warding by day’ to ensure the preservation of the peace.

What became known as the Watch and Ward Act was a response to an escalation of Luddite activity that resulted in machine breaking being made a capital offence. It also came after an attack on Rawfolds Mill, Cleckheaton, in which two rioters were shot and killed by the local militia.7 On the 18th of April, William Cartwright, the owner of Rawfolds Mill, narrowly escaped an attempt on his life. On the 27th of April, William Horsfall, an owner of shearing frames and vociferous critic of the Luddite movement was shot and killed near Huddersfield. In Leeds, food riots led by a character called “Lady Ludd” (see above) broke out as the price of corn increased and, while there is no suggestion of any link with Luddism, the assassination of Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval in May 1812, serves to underline a palpable fear of insurrection in a country that was still waging war against republican France. It was within this context that General Maitland was dispatched to retain order in the North of England and troops deployed to protect the interests of the manufacturers. The seriousness of the situation is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that Wellington’s army in the Peninsula numbered less than the troops (including local militia) deployed to suppress the Luddites in 1812.8 Unsurprisingly, the attack at Gildersome took place just a few weeks after troops detailed to protect Lindsey’s premises had been withdrawn.

The withdrawal of troops from Gildersome becomes of particular interest in light of a letter written by Captain Francis Raynes of the Stirling Militia to his commanding officer, General Acland.9 Summarising the events of the previous few months, Raynes stated that ‘Immediately on the troops being withdrawn, I heard a report that Mr Lindsey of Gildersome intended taking down his shears, and to advertise that he had done so.’ Captain Raynes travelled to Gildersome from his quarters at nearby Mill Bridge, suggesting to Lindsey that removing the shears would ‘show too much fear of the croppers.’ Lindsey, according to Raynes, ‘acknowledged it would be cowardly’ and determined to keep them going.

Lindsey’s apparent willingness to dismantle his own shearing frames in order to avoid the attentions of the rioters presents a clear indication of the threat posed by the Luddites in the area. It also suggests a sense of helplessness. On the 7th of September, the day after the raid on the Old Hall Mill, William Lindsey, in answer to a letter from the Reverend Hammond Roberson, outlined the events of the previous evening. Lindsey concluded his statement by saying that ‘we are now almost at a loss what to do as there are no soldiers in this neighbourhood and it appears evident that nothing but force of arms will secure our property.’10

The fact that Lindsey’s letter was immediately forwarded to General Acland at his headquarters at Wakefield confirms the active role played by Hammond Roberson during the Luddite crisis; he served as chaplain to the Birstall and Batley Militia. Added to which, his address at Healds Hall, Liversedge, placed him within a few hundred yards of Captain Raynes and his troop of militia stationed at Mill Bridge. In his letter, Roberson describes Lindsey as his ‘respected friend’ and there can be little doubt that the two would have been acquainted. Roberson also had strong familial links to Gildersome. His late wife had been a Gildersome girl. Phoebe Roberson, nee Ashworth, had been brought up a Baptist; her father, Thomas Ashworth, had been the minister of Gildersome’s Baptist Chapel. Phoebe’s mother, Mary Priestley, from Fieldhead, Birstall, was a first cousin of Dr Joseph Priestley.

The marriage of a Church of England parson to the daughter of a Baptist minister would have been controversial, to say the least. When we take into account that Hammond Roberson is reputed to have been a sworn enemy of the nonconformists the controversy is considerably enhanced. Roberson was a Norfolk man who took up a curacy at Dewsbury after graduating from Cambridge. Appalled by the apparent weakness of the established church and the ubiquitous presence and influence of the dissenters in and around the Spen Valley, he made it his mission to ‘educate those who could afford no schooling and restore them to the proper established church of the nation’.11 In the pursuit of which, Roberson is credited with establishing the first Sunday school in the North of England.12 His marriage to Phoebe Ashworth, therefore, seems surprising to say the least. P H Booth, in his History of Gildersome and the Booth Family, relates that, despite her marriage to the Liversedge parson, Phoebe insisted on attending the Baptist chapel at Gildersome. It is then alleged that Roberson put an end to his wife’s excursions by shooting her pony in a fit of rage. Following Phoebe’s death in 1810, Roberson compounded his misdemeanour by using his wife’s inheritance to build a church at Liversedge. He had effectively, according to Booth, used nonconformist money to build an Anglican church.13 However, it is not beyond the scope of possibility that Booth’s version of events may be coloured by his own antagonism toward the established church and against a man whose character was already stained in local memory by the events of 1812.14 After the attack on Rawfolds Mill, two wounded prisoners had been taken to the Star Inn at Robert Town for medical assistance. In those days, surgery was carried out with little more than alcohol for anaesthetic. The agonised screams heard from within had lead to suspicions among the onlookers that torture was being used. It was also suggested that Nitric Acid had been used to cauterize the wounds and also (it is alleged) to induce the men to inform on their comrades. Hammond Roberson was certainly present at the event and was assumed to be one of the interrogators.15 It may be the case that Booth’s characterisation of Roberson as a tyrant was widely accepted because he was simply adding to an already tarnished reputation.

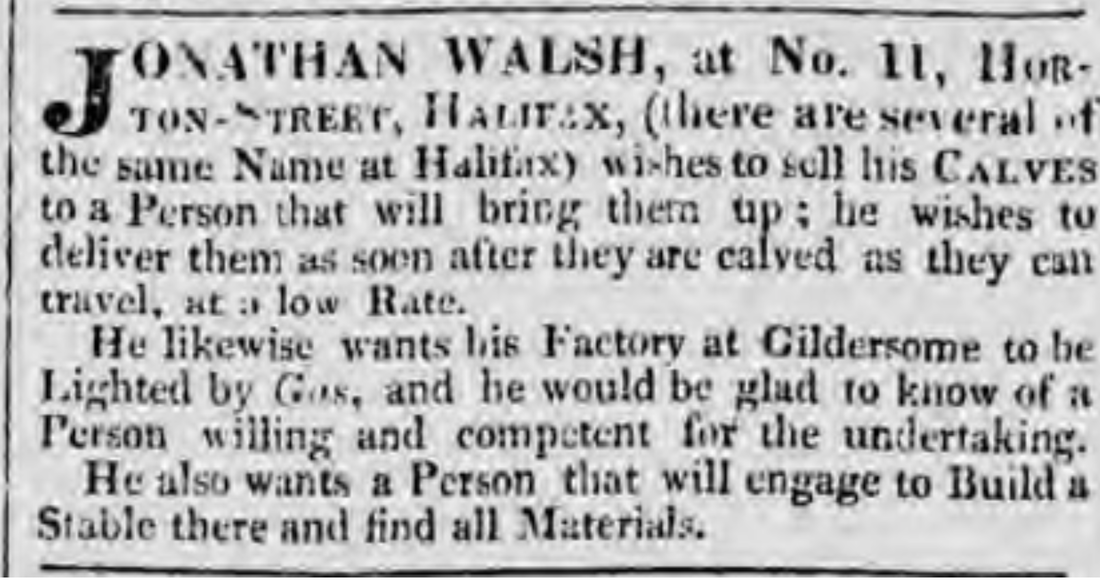

A deed registered at Wakefield in 1807 confirms that at the time of the Luddite attack, the Old Hall estate was owned by Jonathan Walsh of Halifax (Lindsey and Sons were Walsh’s tenants). Walsh has been described as a landowner, moneylender and textile manufacturer. Caroline Walker, a contemporary diarist and near neighbour, described him as an “old usurer” and a man who was “extremely importunate.” From the evidence available, it seems that Walsh was a colourful character, standing well over six feet tall and accustomed to riding from place to place on a donkey. He was also in the habit of carrying a whip and was not averse to using it. Walsh was also notoriously litigious, being reputed to have said that he ‘would rather spend a pound on law than a penny on ale.’ When he died in 1823, despite owning the Old Hall at Gildersome, Dove House at Shibden and Coldwell Hill Farm at Southowram, Walsh was living in a very modest house in a back street in Halifax; his only affectation of luxury being an old silver teapot. According to one newspaper report, Walsh was a miser who ‘in the midst of wealth, … was haunted by the terrors of poverty.’16

What became known as the Watch and Ward Act was a response to an escalation of Luddite activity that resulted in machine breaking being made a capital offence. It also came after an attack on Rawfolds Mill, Cleckheaton, in which two rioters were shot and killed by the local militia.7 On the 18th of April, William Cartwright, the owner of Rawfolds Mill, narrowly escaped an attempt on his life. On the 27th of April, William Horsfall, an owner of shearing frames and vociferous critic of the Luddite movement was shot and killed near Huddersfield. In Leeds, food riots led by a character called “Lady Ludd” (see above) broke out as the price of corn increased and, while there is no suggestion of any link with Luddism, the assassination of Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval in May 1812, serves to underline a palpable fear of insurrection in a country that was still waging war against republican France. It was within this context that General Maitland was dispatched to retain order in the North of England and troops deployed to protect the interests of the manufacturers. The seriousness of the situation is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that Wellington’s army in the Peninsula numbered less than the troops (including local militia) deployed to suppress the Luddites in 1812.8 Unsurprisingly, the attack at Gildersome took place just a few weeks after troops detailed to protect Lindsey’s premises had been withdrawn.

The withdrawal of troops from Gildersome becomes of particular interest in light of a letter written by Captain Francis Raynes of the Stirling Militia to his commanding officer, General Acland.9 Summarising the events of the previous few months, Raynes stated that ‘Immediately on the troops being withdrawn, I heard a report that Mr Lindsey of Gildersome intended taking down his shears, and to advertise that he had done so.’ Captain Raynes travelled to Gildersome from his quarters at nearby Mill Bridge, suggesting to Lindsey that removing the shears would ‘show too much fear of the croppers.’ Lindsey, according to Raynes, ‘acknowledged it would be cowardly’ and determined to keep them going.

Lindsey’s apparent willingness to dismantle his own shearing frames in order to avoid the attentions of the rioters presents a clear indication of the threat posed by the Luddites in the area. It also suggests a sense of helplessness. On the 7th of September, the day after the raid on the Old Hall Mill, William Lindsey, in answer to a letter from the Reverend Hammond Roberson, outlined the events of the previous evening. Lindsey concluded his statement by saying that ‘we are now almost at a loss what to do as there are no soldiers in this neighbourhood and it appears evident that nothing but force of arms will secure our property.’10

The fact that Lindsey’s letter was immediately forwarded to General Acland at his headquarters at Wakefield confirms the active role played by Hammond Roberson during the Luddite crisis; he served as chaplain to the Birstall and Batley Militia. Added to which, his address at Healds Hall, Liversedge, placed him within a few hundred yards of Captain Raynes and his troop of militia stationed at Mill Bridge. In his letter, Roberson describes Lindsey as his ‘respected friend’ and there can be little doubt that the two would have been acquainted. Roberson also had strong familial links to Gildersome. His late wife had been a Gildersome girl. Phoebe Roberson, nee Ashworth, had been brought up a Baptist; her father, Thomas Ashworth, had been the minister of Gildersome’s Baptist Chapel. Phoebe’s mother, Mary Priestley, from Fieldhead, Birstall, was a first cousin of Dr Joseph Priestley.

The marriage of a Church of England parson to the daughter of a Baptist minister would have been controversial, to say the least. When we take into account that Hammond Roberson is reputed to have been a sworn enemy of the nonconformists the controversy is considerably enhanced. Roberson was a Norfolk man who took up a curacy at Dewsbury after graduating from Cambridge. Appalled by the apparent weakness of the established church and the ubiquitous presence and influence of the dissenters in and around the Spen Valley, he made it his mission to ‘educate those who could afford no schooling and restore them to the proper established church of the nation’.11 In the pursuit of which, Roberson is credited with establishing the first Sunday school in the North of England.12 His marriage to Phoebe Ashworth, therefore, seems surprising to say the least. P H Booth, in his History of Gildersome and the Booth Family, relates that, despite her marriage to the Liversedge parson, Phoebe insisted on attending the Baptist chapel at Gildersome. It is then alleged that Roberson put an end to his wife’s excursions by shooting her pony in a fit of rage. Following Phoebe’s death in 1810, Roberson compounded his misdemeanour by using his wife’s inheritance to build a church at Liversedge. He had effectively, according to Booth, used nonconformist money to build an Anglican church.13 However, it is not beyond the scope of possibility that Booth’s version of events may be coloured by his own antagonism toward the established church and against a man whose character was already stained in local memory by the events of 1812.14 After the attack on Rawfolds Mill, two wounded prisoners had been taken to the Star Inn at Robert Town for medical assistance. In those days, surgery was carried out with little more than alcohol for anaesthetic. The agonised screams heard from within had lead to suspicions among the onlookers that torture was being used. It was also suggested that Nitric Acid had been used to cauterize the wounds and also (it is alleged) to induce the men to inform on their comrades. Hammond Roberson was certainly present at the event and was assumed to be one of the interrogators.15 It may be the case that Booth’s characterisation of Roberson as a tyrant was widely accepted because he was simply adding to an already tarnished reputation.

A deed registered at Wakefield in 1807 confirms that at the time of the Luddite attack, the Old Hall estate was owned by Jonathan Walsh of Halifax (Lindsey and Sons were Walsh’s tenants). Walsh has been described as a landowner, moneylender and textile manufacturer. Caroline Walker, a contemporary diarist and near neighbour, described him as an “old usurer” and a man who was “extremely importunate.” From the evidence available, it seems that Walsh was a colourful character, standing well over six feet tall and accustomed to riding from place to place on a donkey. He was also in the habit of carrying a whip and was not averse to using it. Walsh was also notoriously litigious, being reputed to have said that he ‘would rather spend a pound on law than a penny on ale.’ When he died in 1823, despite owning the Old Hall at Gildersome, Dove House at Shibden and Coldwell Hill Farm at Southowram, Walsh was living in a very modest house in a back street in Halifax; his only affectation of luxury being an old silver teapot. According to one newspaper report, Walsh was a miser who ‘in the midst of wealth, … was haunted by the terrors of poverty.’16

|

The first sentence of this advert from 1817 gives an idea of Walsh’s inclination to reduce expenditure wherever possible (and of contemporary attitudes to animal welfare). The second sentence appears to suggest that Walsh was something of an innovator, though his primary objective was likely to have been enabling the operatives to work longer hours.

|

As well as being careful with his money, Walsh was noted for his eccentricity. On the death of his wife, Walsh had her buried in a corner of a field at his farm at Southowram. When he died, he arranged to have his own body interred in the opposite corner of the same field. This was not done simply to avoid the cost of a conventional funeral, or even to maintain a safe distance from his wife. The field in question was close to an old packhorse road. It appears that Walsh had a long-standing dispute with local weavers taking a short cut across his land. In those days it was widely believed that the soul of anyone buried in un-consecrated ground would be doomed to roam the earth in a state of perpetual unrest. It seems that Walsh’s intention was that future trespassers would be deterred by the thought of his spirit haunting the field. While there is no evidence to confirm whether his ploy had worked or not, his body was accidentally discovered in 1896 and placed on public display.17 Unfortunately, the exhibition came to a premature conclusion when the skeleton was kicked to pieces by a group of drunken colliers.

In addition to Walsh’s eccentricities, it seems that he was also a champion of free speech. In 1818, the prosecution of the reformist William Hone, for publishing seditious material, instigated a nationwide, public subscription to fund his defence in court. Jonathan Walsh of Halifax appears on the list of subscribers, donating £5 to the cause.18 This would have been a sizeable donation in 1818, particularly from a man with a reputation for being careful with his money.

In addition to Walsh’s eccentricities, it seems that he was also a champion of free speech. In 1818, the prosecution of the reformist William Hone, for publishing seditious material, instigated a nationwide, public subscription to fund his defence in court. Jonathan Walsh of Halifax appears on the list of subscribers, donating £5 to the cause.18 This would have been a sizeable donation in 1818, particularly from a man with a reputation for being careful with his money.

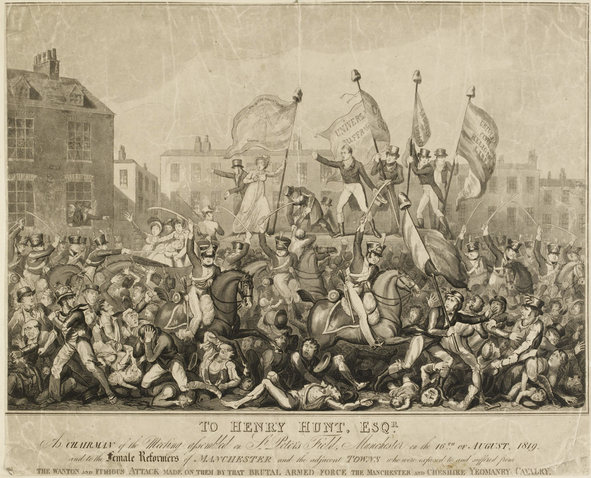

As alluded to above, the Luddite rising of 1812 had been summarily brought to a conclusion by the hanging of seventeen men in 1813. However, it would be wrong to assume that the country’s political and economic landscape had been restored to equanimity. Three years after the Luddite attack on the Old Hall factory, the Bilbrough chronicler writes that one of his relatives living at Bruntcliffe had felt it necessary to ‘remove to a house in “the Town” as they called Gildersome.’19 The writer goes on to say that ‘the introduction of new machinery by the mill owners [continued to] spread dissatisfaction throughout the district and the peace was broken by mobs of people whose work had been taken out of their hands.’ It is interesting to note that Gildersome was perceived to be a safe location, though it should be borne in mind that Bruntcliffe, at that time, was an ‘outlying hamlet’ straddling the intersection of two major highways in the area: the ancient Wakefield to Bradford road and the old coach road connecting Leeds and Manchester. Any “mobs” of dissatisfied workers were likely, therefore, to pass through Bruntcliffe on their way to their various depredations.20 The passage also makes it clear that political agitation continued to be a problem: a problem that would result in national disgrace at a Reformist meeting in Manchester in 1819.

This engraving by Richard Carlile, above, depicts the Reformist meeting at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, being brutally interrupted by the Manchester Yeomanry. Click on image to expand.

This engraving by Richard Carlile, above, depicts the Reformist meeting at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, being brutally interrupted by the Manchester Yeomanry. Click on image to expand.

We have seen above that Jonathan Walsh was something of a political reformer. Curiously, one of his tenants at the Old Hall appears to have shared Walsh’s Reformist inclinations. In the aftermath of what became known as the Peterloo Massacre (1819), Richard Carlile, who had been scheduled to speak at the meeting at St Peters Field was tried and convicted of blasphemy and seditious libel. Carlile’s crime was to have published an open letter to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, entitled “On the Conduct of the Magisterial Yeomanry Assassins of Manchester, on the 16th of August, 1819.” Before the trial was held, Carlile was granted bail. That surety was provided by one Richard Lindsey of Gildersome. Richard Lindsey, along with his brother William and his father Richard senior, had been Walsh’s tenants and proprietors of the Old Hall Mill when the luddites struck in 1812. It is intriguing to see that a man whose livelihood had already suffered at the hands of social unrest remained an active supporter of political reform seven years later.

Lindsey’s involvement also drew a particularly hostile attack from the Leeds Intelligencer (1819) in an article entitled a “Specimen of a Reformer’s Morality.” The writer of which notes that Lindsey ‘assumes the garb of a Quaker.’ It goes on to claim that Lindsey has been disowned by that sect because of his involvement with Reformist politics and with Carlile in particular. However, the newspaper’s claims are thrown into doubt by the fact that Richard Lindsey of Mirfield, formerly of Gildersome, was buried at the Friends’ Burial Ground at Brighouse in February 1835. We must assume that either Lindsey’s exclusion from the Society of Friends had been a temporary measure, or the newspaper’s attack on his character had been mendacious. Given the tone of the article,

I am inclined to side with the latter.

That the owners and occupiers of Gildersome’s Old Hall have been largely forgotten to history should come as no surprise. At the time of writing, Gildersome is a handful of fields away from absorption into the nearby conurbations of Leeds and Bradford and its former inhabitants are of little consequence to the modern consciousness. However, in 1812, the situation was very different. Gildersome, although part of Batley Parish, was a township in its own right, conducting its own affairs in a spirit of independence. That independence might be said to be reflected in those manufacturers who determined to embrace the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution in the face of social upheaval and what many at the time feared might be outright revolution. The ability to think and act independently is reflected in characters willing to take up arms against the rioters, and to do so even while maintaining an active involvement in political reform. It is also evident in those who chose to bury their wives in the corner of a field.

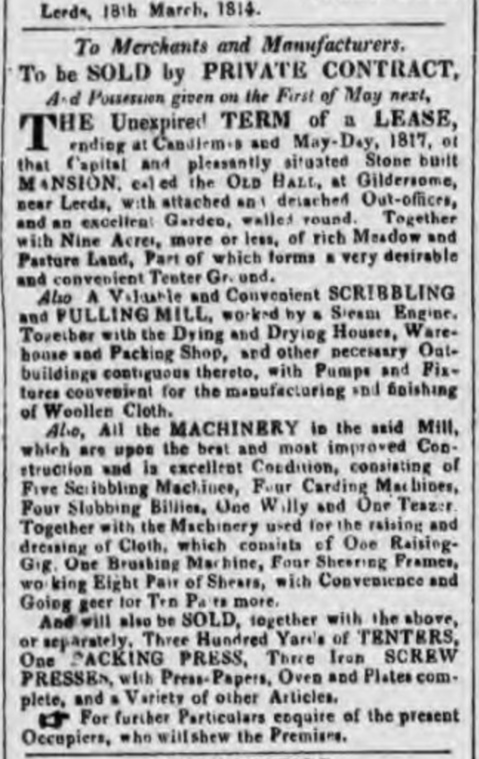

This advert from the Leeds Intelligencer (1809) presents a detailed inventory of the fixtures and fittings at Gildersome’s Old Hall. The factory fittings would have been pretty much the same that would attract the attention of the Luddites in 1812. It is likely that Lindsey and Sons went out of business around 1814, though, whatever the outcome of the proposed sale, records show that Jonathan Walsh remained the owner until his death in 1823.

Lindsey’s involvement also drew a particularly hostile attack from the Leeds Intelligencer (1819) in an article entitled a “Specimen of a Reformer’s Morality.” The writer of which notes that Lindsey ‘assumes the garb of a Quaker.’ It goes on to claim that Lindsey has been disowned by that sect because of his involvement with Reformist politics and with Carlile in particular. However, the newspaper’s claims are thrown into doubt by the fact that Richard Lindsey of Mirfield, formerly of Gildersome, was buried at the Friends’ Burial Ground at Brighouse in February 1835. We must assume that either Lindsey’s exclusion from the Society of Friends had been a temporary measure, or the newspaper’s attack on his character had been mendacious. Given the tone of the article,

I am inclined to side with the latter.

That the owners and occupiers of Gildersome’s Old Hall have been largely forgotten to history should come as no surprise. At the time of writing, Gildersome is a handful of fields away from absorption into the nearby conurbations of Leeds and Bradford and its former inhabitants are of little consequence to the modern consciousness. However, in 1812, the situation was very different. Gildersome, although part of Batley Parish, was a township in its own right, conducting its own affairs in a spirit of independence. That independence might be said to be reflected in those manufacturers who determined to embrace the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution in the face of social upheaval and what many at the time feared might be outright revolution. The ability to think and act independently is reflected in characters willing to take up arms against the rioters, and to do so even while maintaining an active involvement in political reform. It is also evident in those who chose to bury their wives in the corner of a field.

This advert from the Leeds Intelligencer (1809) presents a detailed inventory of the fixtures and fittings at Gildersome’s Old Hall. The factory fittings would have been pretty much the same that would attract the attention of the Luddites in 1812. It is likely that Lindsey and Sons went out of business around 1814, though, whatever the outcome of the proposed sale, records show that Jonathan Walsh remained the owner until his death in 1823.

Footnotes:

1) The incident was widely reported in contemporary newspapers. The information above is taken from the London Courier, September 1812.

2) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.549.

3) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.548.

4) Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales Vol. 2.

5) Chronicles of my Ancestors, William Radford Bilbrough, Bilbrough and Town Collection, WYAS Leeds.

6) WYAS Q01/231/31

7) The attack on Rawfolds Mill was dramatized by Charlotte Bronte in Shirley (1849).

8) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.617.

9) The deployment of the Stirling Militia is corroborated by Frank Peel who notes that they were based at Huddersfield. Peel, F. 1880 The Risings of the Luddites Heckmondwike: TW Senior.

10) HO 40/2/3

11) Reid, R. Land of Lost Content: The Luddite Revolt, 1812. London: Sphere Books. P.13.

12) Ibid

13) Nussey, JTM. Hammond Roberson of Liversedge (1757-1841)- Bully or Gentleman? The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol. 53, 1981. John Nussey has drawn attention to the inconsistencies in Booth’s account and the details of Mary Ashworth’s will which casts doubt on the assumption that nonconformist money was used to build the church at Liversedge. However, Nussey fails to explain how a curate from a modest background in Norfolk actually found the means to purchase Healds Hall and build a new church.

14) Booth family documents reveal that ‘in the Ashworth family it is a well recognised and authenticated fact that there existed a taint of insanity.’ That PH Booth neglects to mention this in his critique of Roberson’s relationship with Phoebe Ashworth may be of significance.

15) Reid, R. Land of Lost Content: The Luddite Revolt, 1812. London: Sphere Books. P.115.

16) Manchester Mercury, March, 1823. An element of journalistic license is revealed when the same article describes the Old Hall as a ’stately mansion’ standing in a ‘handsome estate at Gildersome.’

17) Coldwell Hill Farm was leased to the quarrying firm of Maude and Dyson. When Walsh’s remains were disturbed by their activities, they enterprisingly put his skeleton on display at a charge of two pence per view. It is tempting to think that Walsh might have approved.

18) The Globe, Jan 27, 1818.

19) Chronicles of my Ancestors, William Radford Bilbrough, Bilbrough and Town Collection, WYAS Leeds.

20) Gelderd Road, which replaced the old coach road between Leeds and Manchester thru Morley, was yet to be constructed. When it was, Gildersome would have been more readily exposed to any “disaffected mobs .“

1) The incident was widely reported in contemporary newspapers. The information above is taken from the London Courier, September 1812.

2) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.549.

3) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.548.

4) Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales Vol. 2.

5) Chronicles of my Ancestors, William Radford Bilbrough, Bilbrough and Town Collection, WYAS Leeds.

6) WYAS Q01/231/31

7) The attack on Rawfolds Mill was dramatized by Charlotte Bronte in Shirley (1849).

8) Thompson E.P. 1963 The Making of the English Working Class, Harmondsworth: Penguin p.617.

9) The deployment of the Stirling Militia is corroborated by Frank Peel who notes that they were based at Huddersfield. Peel, F. 1880 The Risings of the Luddites Heckmondwike: TW Senior.

10) HO 40/2/3

11) Reid, R. Land of Lost Content: The Luddite Revolt, 1812. London: Sphere Books. P.13.

12) Ibid

13) Nussey, JTM. Hammond Roberson of Liversedge (1757-1841)- Bully or Gentleman? The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol. 53, 1981. John Nussey has drawn attention to the inconsistencies in Booth’s account and the details of Mary Ashworth’s will which casts doubt on the assumption that nonconformist money was used to build the church at Liversedge. However, Nussey fails to explain how a curate from a modest background in Norfolk actually found the means to purchase Healds Hall and build a new church.

14) Booth family documents reveal that ‘in the Ashworth family it is a well recognised and authenticated fact that there existed a taint of insanity.’ That PH Booth neglects to mention this in his critique of Roberson’s relationship with Phoebe Ashworth may be of significance.

15) Reid, R. Land of Lost Content: The Luddite Revolt, 1812. London: Sphere Books. P.115.

16) Manchester Mercury, March, 1823. An element of journalistic license is revealed when the same article describes the Old Hall as a ’stately mansion’ standing in a ‘handsome estate at Gildersome.’

17) Coldwell Hill Farm was leased to the quarrying firm of Maude and Dyson. When Walsh’s remains were disturbed by their activities, they enterprisingly put his skeleton on display at a charge of two pence per view. It is tempting to think that Walsh might have approved.

18) The Globe, Jan 27, 1818.

19) Chronicles of my Ancestors, William Radford Bilbrough, Bilbrough and Town Collection, WYAS Leeds.

20) Gelderd Road, which replaced the old coach road between Leeds and Manchester thru Morley, was yet to be constructed. When it was, Gildersome would have been more readily exposed to any “disaffected mobs .“