Gildersome Park? © Charles Soderlund Oct, 2020

On this page I wish to present certain natural and artificial features in Gildersome and Farnley which, due to their relationship, suggest a purposeful design, possibly as a game reserve, hunting park or both. In addition, certain place names there, which have survived into the 19th and 20th century, such as pale, park etc, add further circumstantial evidence and serve to support the claim. Game and forest reserves as well as deer hunting enclosures, called deer-hays during the Saxon reign and deer parks under the Normans, have been in existence in England since Saxon times, reaching their zenith in the 13th and 14th century under the Normans. In many cases, these parks have been identified by their circular shape, the preferred design that saved time and money. Once built, the park's perimeter became known as the ring and could include many components, most often a pale (fence and ditch), but also natural boundaries such as a cliff face, river and a stream embankment. It's also possible that, if any such park did exist in Gildersome, it came to an end with the discovery and exploitation of accessible iron ore at Harthill. (Note, from this point on the term park or deer park will be used to indicate all reserves, deer hays, deer parks etc.)

|

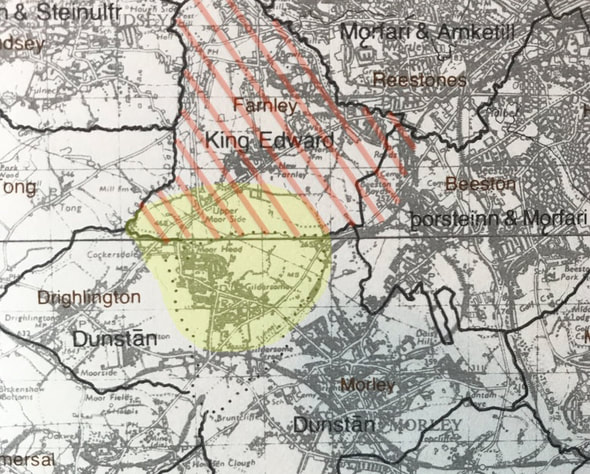

This detail of a map, right, from an archaeological study, shows pre Conquest townships and their borders.(1) A township's name is marked in brown and its tenant in chief in a bolder black. Gildersome is represented by a dotted line which delineates its future border (found mostly within the yellow shaded area). To whom did it belong? It shared three somewhat equal borders with Morley, Drighlington and Farnley. On the map, Farnley is marked by red diagonal lines. As one can see, it has no southern border. The yellow represents most of Gildersome and some of Farnley, and indicates the area of a hypothetical deer park. (click on the map for a larger version)

|

The above mentioned study assumed that, at the time of the Norman Conquest, Gildersome's area belonged to either the township of Morley or Drighlington. However, it's also possible that Gildersome's land was considered Farnley and thus belonged to King Edward prior to the Normans (more on the Farnley connection later).

|

Before discussing the extent and boundaries of a park at Gildersome, let's start with Harthill which coincidentally lies at its centre. By virtue of its prominent position, people have visited and perhaps used Harthill for as long as Britain has been occupied. So it's safe to say, that during that time, it had many different names. But, it's the present name, Harthill, which piques my interest. Possibly the name alludes to some mythic apparition seen wandering about the hill crest, a White Stag perhaps? Should that be the case, the tale of that vision has been lost with the passing of time. The simplest explanation would be to associate the name "Hart" with a medieval hunt, and not just hunting for the masses, rather a hunt set aside exclusively for the king or his nobles, with his permission of course. In his book, Medieval Hunting, Richard Almond (2) says this about the Hart:

|

It was the 'great hart' however, which held the premier position as noble quarry. These beasts, at least six years old with ten points or tines to their rack of antlers, were often described as 'warrantable' in the hunting treatises. 'The Master of the Game' specifies the male red deer as correctly being termed as in 'the fifth [year] a stag: the sixth year a hart of ten and first [year] he is chaseable, for always before shall he be called rascal or folly'. The hart was regarded as royal game, and so belonged to the king or ruler of the country. Hunting the wild hart was thus a royal prerogative and a courtly activity, although special licences to take red deer and other game were granted on occasion by the sovereign to specially favoured courtiers.

I believe that there's a high probability that Harthill refers to a lord's, or possibly a king's, hunting reserve. Keep that in mind when reading the following analysis of the park-like features of Gildersome. (Note: The intent of this article is not to discuss the activities within a park unless it's necessary to explain a geographic feature.)

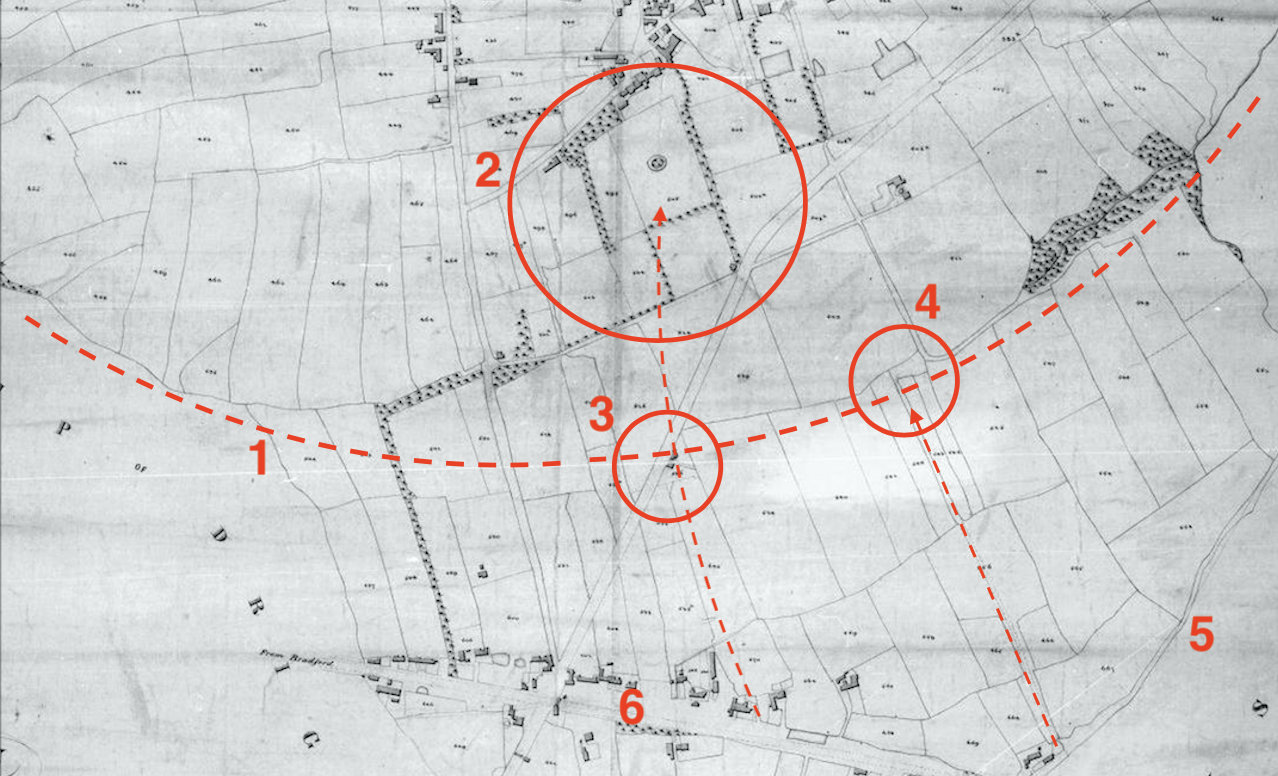

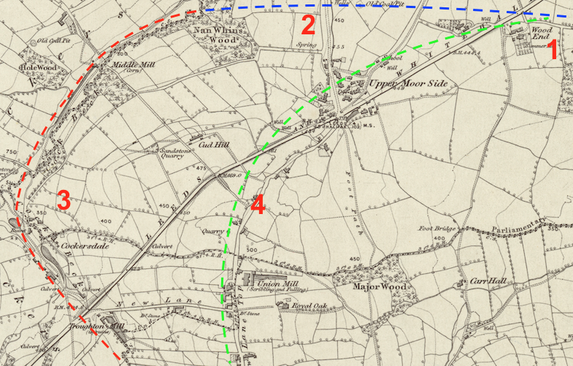

On the map below, the space within the many coloured dotted lines represents the same space shown shaded yellow on the map above. It also indicates the approximate location of a ring fence (pale) which may have encircled a park. In the map, its perimeter has been divided into five sections. Each section, except for section 1 is still in existence today. The larger white dashed line indicates a possible alternative, shortening the perimeter by removing from it sections 4 & 5. Harthill can be found in its centre.

On the map below, the space within the many coloured dotted lines represents the same space shown shaded yellow on the map above. It also indicates the approximate location of a ring fence (pale) which may have encircled a park. In the map, its perimeter has been divided into five sections. Each section, except for section 1 is still in existence today. The larger white dashed line indicates a possible alternative, shortening the perimeter by removing from it sections 4 & 5. Harthill can be found in its centre.

The following is a discussion of each of the five perimeter sections and numbers 6 thru 9 which appear on the map, above. Each section may include further maps that point out details specific to that section. When alluding to the above map, it shall be called "the big map."

Sections 1 thru 5 on the Big Map:

Section 1: On the 1840s Tithe Map for Gildersome, below, the red dashed line (#1) is the same line depicted as the red dotted line marked section 1 in the big map above. The 1840s map reveals that the majority of the boundaries of the enclosed fields along the dashed line conform to the arc of that line, from Andrew Beck in the west (section 5 big map), and Dean Beck in the east (section 2 big map). Across that area, there's no particularly apparent geographic or topographic reason to account for the configuration of those fields. The large red circle below (#2), is an area called the Park, mentioned in a 16th century document; today, the name Park can still be found attached to many of the streets and some of the houses in the area. The smaller circle beneath (#3) is an area called Spike Gate in the map's corresponding apportionments. The name "Gate" is Old Norse in origin meaning a lane, road or a way through and "Spike" suggests a ring fence or pale whose upright posts are tapered to a point at the top. An ancient footpath, portions of which can still be found today, leading from the highroad to Harthill, passed through Spike Gate. Another pathway, Old Stone Pitts Road (#4), leading from Nipshaw Lane (#5) to the town's centre, was demesne land for at least 800 years. As mentioned previously, Farnley was controlled from the King's estate at Wakefield prior to the Conquest. If a park had been located at the southern end of Farnley (Gildersome), it would seem logical that any entrance to that park would be as close to Wakefield as possible, i.e. somewhere along the Wakefield to Bradford Road. As it happens, this proposed park is close to the intersection of two ancient highroads, the Wakefield to Bradford (#6) and the Leeds to Manchester roads (#5). Both Spike Gate and Old Stone Pitts Road are excellent candidates for an entrance, however the Stone Pitts entrance is located precisely at the intersection of those aforementioned highroads, therefore seemingly the best of the two.

Sections 1 thru 5 on the Big Map:

Section 1: On the 1840s Tithe Map for Gildersome, below, the red dashed line (#1) is the same line depicted as the red dotted line marked section 1 in the big map above. The 1840s map reveals that the majority of the boundaries of the enclosed fields along the dashed line conform to the arc of that line, from Andrew Beck in the west (section 5 big map), and Dean Beck in the east (section 2 big map). Across that area, there's no particularly apparent geographic or topographic reason to account for the configuration of those fields. The large red circle below (#2), is an area called the Park, mentioned in a 16th century document; today, the name Park can still be found attached to many of the streets and some of the houses in the area. The smaller circle beneath (#3) is an area called Spike Gate in the map's corresponding apportionments. The name "Gate" is Old Norse in origin meaning a lane, road or a way through and "Spike" suggests a ring fence or pale whose upright posts are tapered to a point at the top. An ancient footpath, portions of which can still be found today, leading from the highroad to Harthill, passed through Spike Gate. Another pathway, Old Stone Pitts Road (#4), leading from Nipshaw Lane (#5) to the town's centre, was demesne land for at least 800 years. As mentioned previously, Farnley was controlled from the King's estate at Wakefield prior to the Conquest. If a park had been located at the southern end of Farnley (Gildersome), it would seem logical that any entrance to that park would be as close to Wakefield as possible, i.e. somewhere along the Wakefield to Bradford Road. As it happens, this proposed park is close to the intersection of two ancient highroads, the Wakefield to Bradford (#6) and the Leeds to Manchester roads (#5). Both Spike Gate and Old Stone Pitts Road are excellent candidates for an entrance, however the Stone Pitts entrance is located precisely at the intersection of those aforementioned highroads, therefore seemingly the best of the two.

|

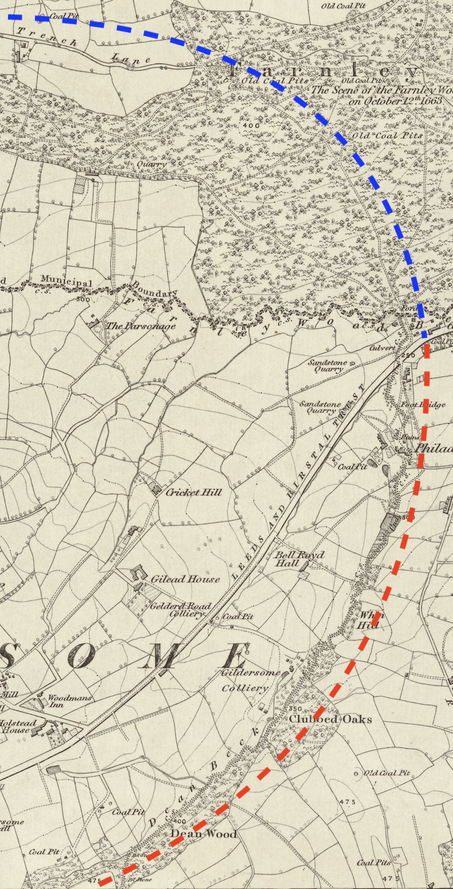

Sections 2 and 3: On the map, right, Dean Beck (section 2) is indicated by the red line and Trench Lane (section 3) by the blue. The Dean Beck section ends where it merges with Trench Lane, at Farnley Wood Beck, and then continues to arc to the west. Despite some inevitable meandering, Dean Beck's channel appears to have been purposefully sculpted as it was sometimes when Medieval parks were built. An archaeological survey of the remaining portions of its east and south east banks might turn up evidence of a pale.

Above, a section of Wood Lane today. (3)

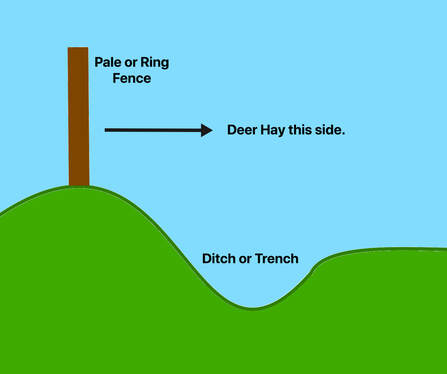

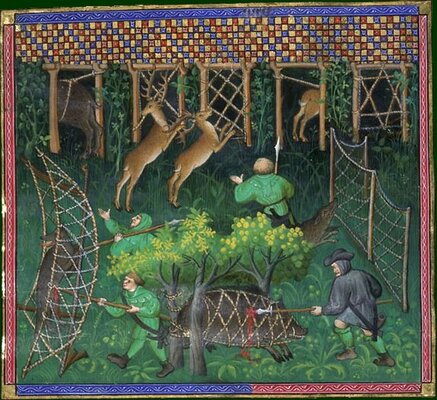

Trench Lane's name had existed for centuries. Today it's called Wood Lane. The lane can be seen in the 1852 O.S. map (right) stretching from Gelderd Rd. to Tong Beck, with only a few short diversions. It was involved in the 1663 failed rebellion's Farnley Wood Plot, and was known to be the meeting place of the conspirators. Many people believe that it was so named because a trench was constructed there during the Battle of Adwalton Moor (1643). However, prior to that battle, I don't believe there was sufficient reason or time to waste men in a wood through which no highroad passed. It's my contention that "trench" refers to a ditch that was dug at the foot of a ring fence (either a hedge or wooden posts). In a typical park some, if not all, of its interior is encircled by a ring fence and ditch, called the Pale. The trench was dug well below ground level and, when combined with the height of a fence, created a distance too high for even the most athletic of deer to jump. Many pales were constructed to allow a deer access into the park, but not to escape once inside. (see right) |

|

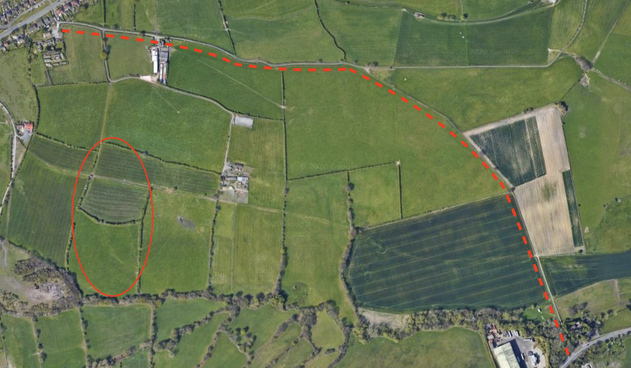

Above is a Google satellite view of old Trench Lane still in existence. The oval is #6 on the big map above, and marks two enclosed fields called in 1843 Bone Field and the Shambles, Old English for butchering site.

|

Below is a mid 1700s map which shows Trench Lane connecting with Rooms Lane. The connection site was somewhere near today's Gelderd Road.

Click on either of these two images to enlarge.

|

|

Section 4: Tong Beck. On the map, left, #1 is the continuation of Trench Lane from the map above, and #2 is the proposed line of a ring fence (both in blue). #3 is Tong Beck that merges with Cock Beck at Cockersdale. At New Lane, where highground separates the streams, Andrew Beck carries on to complete the ring. #4 is an alternate perimeter, bypassing Tong and Andrew becks, making a potential park smaller. Later, during the Middle Ages, Cockersdale and Tong Beck would become a valuable iron working region. Click image to expand.

|

In a part of a 1526 indenture between Christopher Danby of Farnley and Peter Merfeld of Tong concerning "the right title and possession of common pasture for themselves and their tenants in Fernelay and Tong,"(4) Tong Beck is called "Rynghaybeke." This is highly significant because "Ryng" (Ring) is a reference to a park's perimeter and "hey" was the Saxon's term for deer park. The following is an excerpt from that 1526 indenture:

....."as well as the Est part of oon beke or brook callyd Rynghaybeke as also the West part of the same Rynghaybeke, which beke is a dyvysyon and lymet os bownd betwix the lordships of Fernelay and Tong"

(In today's English: "as well as the east part of a beck or brook called Ringheybeck (and) also the west part of the same

Ringheybeck the said beck is a division and limit or boundary between the townships of Farnley and Tong")

There's no doubt that the above quote was referring to today's Tong Beck. Clearly the park had been on the Farnley side since maps from the early 1600s, like the one below left, reveal a park there but none at Tong. "Ryngheybeke" definitely refers to a part of a park's perimeter where the beck's embankment, in this case on the Tong side, was utilised as a ditch and, situated at its crest would have been a hedge or wooden fence. As stated above, parks used natural landscape whenever possible and in some cases they were laboriously altered when the need suited. Interestingly, the term "hay" is of Saxon origin while "park" derives from French, this suggests a Saxon origin for Farnley's park rather than Norman.

In addition, the above mention of common pasture implies that, by 1526, any Medieval park had long since contracted though the name Ryngehaybeke had endured.

Right, in this 1610 map of West Yorkshire, Farnley Park can be seen in the centre of the image in a classic circular shape.

In addition, the above mention of common pasture implies that, by 1526, any Medieval park had long since contracted though the name Ryngehaybeke had endured.

Right, in this 1610 map of West Yorkshire, Farnley Park can be seen in the centre of the image in a classic circular shape.

Section 5: Andrew Beck is a channel which, for millennia, has drained the area between the west moors of Gildersome and Drighlington. It has that general crescent shape characteristic of Tong and Dean becks and like them, 800 years ago its channel would have been closer to ground level, though its water volume may have been much greater. The two photos below were shot recently at Andrew Beck.(5) The one on the left was shot from the bottom facing the bank on the Drighlington side. The other was shot in the embankment's west rim and gives one the distinct impression that a hedge or fence once topped its brink. In the hundreds of years which have past, many changes have occurred to the beck's landscape making it difficult for an amateur to interpret any remaining landforms, therefore, an archaeological survey of the remaining portions of its west and southwest banks might prove useful.

Below left: Andrew Beck western embankment. Below right: Andrew Beck embankment top.

Below left: Andrew Beck western embankment. Below right: Andrew Beck embankment top.

Numbers 6 thru 9 on the Big Map:

Number 6, Farnley Wood Beck: During the past 1,000 years, soil from the surrounding high ground filled the once steeper vale of the stream, raising the ground to the marshy level seen today. It's not beyond reason that a natural or artificial pond once occupied the circled area at #6 on the big map. A small lake or pond would have been an asset in any game reserve or park.

Number 7, An Open Air Butchering Site?: As mentioned above, the site contains two enclosed fields whose names in the 1843 Tithe Apportionments are Bone Field and the Shambles. Generally, a Shambles is an Old English name for an open air butchering site usually connected to a market setting. The field next to it, called Bone Field, adds validity to the presence of a butchery. So, the question is, what was going on there, where presumably nothing but agriculture had existed for hundreds of years? The names are old and their meaning has passed from memory, but here are some possibilities........

Number 6, Farnley Wood Beck: During the past 1,000 years, soil from the surrounding high ground filled the once steeper vale of the stream, raising the ground to the marshy level seen today. It's not beyond reason that a natural or artificial pond once occupied the circled area at #6 on the big map. A small lake or pond would have been an asset in any game reserve or park.

Number 7, An Open Air Butchering Site?: As mentioned above, the site contains two enclosed fields whose names in the 1843 Tithe Apportionments are Bone Field and the Shambles. Generally, a Shambles is an Old English name for an open air butchering site usually connected to a market setting. The field next to it, called Bone Field, adds validity to the presence of a butchery. So, the question is, what was going on there, where presumably nothing but agriculture had existed for hundreds of years? The names are old and their meaning has passed from memory, but here are some possibilities........

- A deer park butchering site.

- A cattle slaughtering site.

- A Medieval market, though it seem too far off the beaten track.

- A prehistoric fossil site, mistakenly earning the name Shambles.

|

Number 8, Castle Hill: Legend has it that a castle, from some bygone era, once sat upon the crest of Farnley's heights, thus earning it its name. I would like to draw attention to the strange pattern in the field adjacent to Wood Lane (within the blue circle). The impression resembles the perimeter of a large structure or several structures with a courtyard within. This same pattern appears in other satellite view shots as well. Though it may be nothing at all, there's a possibility it may have some connection to a park.

Number 8, Field Names: On the 1843 Tithe Map and Apportionments for Farnley, the following field names are listed for eight of the enclosed fields surrounding the location to the north and west of the location shown in the image, left.

|

Was Gildersome's land combined with Farnley's prior to and after 1066?

Gildersome did not appear in the Domesday Book of 1086. The prevailing theory why is best expressed in this quote from a 1970s archaeological study of West Yorkshire:

Gildersome did not appear in the Domesday Book of 1086. The prevailing theory why is best expressed in this quote from a 1970s archaeological study of West Yorkshire:

"An award of c. 1233 describes Farnley Wood Beck as running 'between the wood of Farneley and the assart of Gildhus, suggesting that Gildersome township, like Longwood, developed from an assart. This would explain its omission from Domesday Book and the Nomina Villarum......Before its emergence as a township, Gildersome must have formed part of either Drighlington or Morley......." (6)

|

The reasonableness of this is beyond fault. Both Morley and Drighlington were existing townships in 1066, and unrecorded Gildersome lay in between. It's a fact that no one really knows how the 1,000 acres of land, that was later to become Gildersome, was allocated. The acreage shared a border with Morley as well as Drighlington, so it's safe to assume that it either belonged to one or the other or that each township controlled a portion. However, the pre- Gildersome territory also shared a long border with Farnley, a fact which seems to have been overlooked. It might be entirely possible that, during the Saxon reign, Gildersome's land had belonged to Farnley. Given the lack of supportable evidence one way or the other, it's as plausible as any other theory. Farnley did make it into the Domesday book as part of the royal estate of Wakefield, and, at least 100 years thereafter, was recorded as containing a Norman park.

|

Above, foresters assisting a hunt catch deer, boar and wolves in nets.

|

At the time just prior to the Norman Conquest (1066), Farnley was attached to the royal estate of Wakefield, the administrative centre of about 40 townships which were spread out all over West Yorkshire. This grand estate had probably been owned by the kings of England since they retook the North from the Danes. In 1066 it was owned by King Edward the Confessor. Farnley, along with Wakefield's other attached holdings, appeared in the Domesday Book (Phillimore Version). However, the only information gleaned from its entry was that it contained three Carucates of tillable land (360 acres). There was no mention of its current value which was usually directly related to the destruction meted out during the Harrying of the North. During this unhappy episode of Northern history, all of Farnley's close neighbours were laid "waste." Was Farnley destroyed too? We know that the township of Wakefield itself escaped the ruin, perhaps because its new owner, King William, ordered his estates exempt from the retribution. That being the case, it's safe to assume that Farnley was spared also.

An estate the size of Wakefied, made up of over 80 Carucates (about 10,000 tillable acres), would undoubtedly have been relatively self supporting, containing, but not limited to, iron mines and smithies, farmed lands, grazed lands, woodlands, textile industries, etc. It would have also contained one, if not several, deer farms or parks to supply fresh venison for the local nobility and, if ever they were to visit, sport for the king and his courtiers. At some point after Domesday, King William decided to reorganise his holdings in West Yorkshire. Farnley was removed from the control of his Wakefield estate and awarded to Ilbert de Lacy, tenant in chief of the Honour of Pontefract. Mr. de Lacy had tenancy of over 150 townships in Yorkshire, among them were each of Farnley's contiguous neighbours. After the Harrying, West Yorkshire was slow to recover. For the next 100 years, few documents exist describing what must have been a slow repopulation and an even slower return to law and order. Any documents, as well as those with living memories, relating to pre-conquest boundaries had disappeared, thus making a resurvey of the entire area inevitable. The less than prime real estate found in the ridges and hills south of the River Aire were probably last on the surveyor's list. That being so, the boundaries between the various townships in Farnley's vicinity probably weren't fully fixed until after 1160. It was sometime during this transitional period that the de Nevile family was awarded the lordship of Farnley under its tenants in chief, the Lacy's.

An estate the size of Wakefied, made up of over 80 Carucates (about 10,000 tillable acres), would undoubtedly have been relatively self supporting, containing, but not limited to, iron mines and smithies, farmed lands, grazed lands, woodlands, textile industries, etc. It would have also contained one, if not several, deer farms or parks to supply fresh venison for the local nobility and, if ever they were to visit, sport for the king and his courtiers. At some point after Domesday, King William decided to reorganise his holdings in West Yorkshire. Farnley was removed from the control of his Wakefield estate and awarded to Ilbert de Lacy, tenant in chief of the Honour of Pontefract. Mr. de Lacy had tenancy of over 150 townships in Yorkshire, among them were each of Farnley's contiguous neighbours. After the Harrying, West Yorkshire was slow to recover. For the next 100 years, few documents exist describing what must have been a slow repopulation and an even slower return to law and order. Any documents, as well as those with living memories, relating to pre-conquest boundaries had disappeared, thus making a resurvey of the entire area inevitable. The less than prime real estate found in the ridges and hills south of the River Aire were probably last on the surveyor's list. That being so, the boundaries between the various townships in Farnley's vicinity probably weren't fully fixed until after 1160. It was sometime during this transitional period that the de Nevile family was awarded the lordship of Farnley under its tenants in chief, the Lacy's.

Gildersome, then called Gildhus, didn't appear in any surviving records prior to the 1170s. It was not until 1280, that it was first mentioned in a document as a proper township (manor). By then Gildersome must have had an original charter, which unfortunately appears to have been lost. Between those two dates above, only a few names of its inhabitants (the "de Gildhuses") or small landholders can be found in the record but they contain no facts of any value. A noteworthy exception is in 1233, when the parish boundary was set between Leeds and Batley. The line was fixed at the beck between the "wood of Farnley and the assart of Gildhus" (Gildersome).(8) To me, this demarcation implies that Gildersome had not yet risen to the status of a township, it also makes clear that the assart of Gildhus and Farnley were their own distinct entities. Furthermore, if Gildersome and Farnley had once been consolidated, the date 1233 may represent the year of their separation.

It's been the assertion of this article that certain geographic features around Gildersome and Farnley point to the probability that some sort of deer park had existed there in the past. The likelihood that the park was to be found in the Gildersome area, through the Saxon and the Norman reigns, presupposes a park or game reserve existed in Farnley in the first place. But where better to have one? Under the Saxons, Farnley was King's land, and as the "wood of Farnley and the assart of Gilders" reveals, at the very least the southern half of Farnley combined with Gildersome was forested. The most prominent feature of that southern half was called Harthill, the name of an animal protected by decree, in other words; the king's quarry.

Postscript: After the 1233 parish divide, the lure of abundant iron ore may have resulted in the closure of the park around Harthill, but the remainder of the park, within the redefined borders of Farnley carried on. The vestiges of that park can still be found today on the grounds of Farnley Hall.

It's been the assertion of this article that certain geographic features around Gildersome and Farnley point to the probability that some sort of deer park had existed there in the past. The likelihood that the park was to be found in the Gildersome area, through the Saxon and the Norman reigns, presupposes a park or game reserve existed in Farnley in the first place. But where better to have one? Under the Saxons, Farnley was King's land, and as the "wood of Farnley and the assart of Gilders" reveals, at the very least the southern half of Farnley combined with Gildersome was forested. The most prominent feature of that southern half was called Harthill, the name of an animal protected by decree, in other words; the king's quarry.

Postscript: After the 1233 parish divide, the lure of abundant iron ore may have resulted in the closure of the park around Harthill, but the remainder of the park, within the redefined borders of Farnley carried on. The vestiges of that park can still be found today on the grounds of Farnley Hall.

Notes:

1) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Map Volume

2) Medieval Hunting, Richard Almond (2011 History Press)

3) Google Earth Street View

4) Yorkshire Deeds Vol. 10, page 68

5) Photographs courtesy of Andrew Bedford

(6) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

7) Painting by Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759 to 1817)

8) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

1) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Map Volume

2) Medieval Hunting, Richard Almond (2011 History Press)

3) Google Earth Street View

4) Yorkshire Deeds Vol. 10, page 68

5) Photographs courtesy of Andrew Bedford

(6) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281

7) Painting by Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759 to 1817)

8) West Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council, Wakefield, 1981: West Yorkshire: an Archaeological Survey to A.D. 1500, Volume 2, Pg. 281