Gildersome’s Kriegsgefangenen by: Andrew Bedford © 2019

Arthur Taylor circa 1920

Arthur Taylor circa 1920

One of my earliest memories concerns a framed, sepia photograph of a soldier in a kilt. This, I was told, was the man I came to know as “uncle Arthur” – in actuality he was my father’s uncle Arthur, my great uncle. The picture of the man in the kilt always fascinated me and the following is my somewhat belated attempt to make sense of how it came to be. It turned out to be an attempt that stumbled upon the tragic tale of two friends who went to war.

In March 1918, the Weekly Casualty List presented an unusually extensive inventory of soldiers missing in action. Two of the soldiers listed were Gildersome men: Hughes 201459 J, and Taylor 201550 A, both of the 4th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders. The 1911 census lists John Hughes living with his parents and sister on Finkle Lane. The same source shows that Arthur Taylor resided at Hudson’s Nook. The close proximity of their addresses suggests that John and Arthur would certainly have known each other. The even closer proximity of their service numbers suggests that they enlisted together.

In March 1918, the Weekly Casualty List presented an unusually extensive inventory of soldiers missing in action. Two of the soldiers listed were Gildersome men: Hughes 201459 J, and Taylor 201550 A, both of the 4th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders. The 1911 census lists John Hughes living with his parents and sister on Finkle Lane. The same source shows that Arthur Taylor resided at Hudson’s Nook. The close proximity of their addresses suggests that John and Arthur would certainly have known each other. The even closer proximity of their service numbers suggests that they enlisted together.

The area within the purple line was known as Hudson’s Nook. Arthur Taylor lived in the cottage circled. As far as can be ascertained from the census, John Hughes lived in one of the houses in the oval.

The area within the purple line was known as Hudson’s Nook. Arthur Taylor lived in the cottage circled. As far as can be ascertained from the census, John Hughes lived in one of the houses in the oval.

In 1911, John and Arthur were both employed in the mining industry. In the census, John, aged 18, is listed as a “trammer” and Arthur, aged 17, as a “hurrier.” If my understanding is correct, both terms refer to the same job: hauling coal from the coalface to the shaft (a job, incidentally, that Arthur’s father had done at the age of 9). It is not beyond reason to surmise that John and Arthur could have worked at the same colliery, although no records exist to confirm this. Before the war, Arthur worked at the Howden Clough Colliery, so it is possible that John worked at the same place. What is certain is that both would have been classified as being in “reserved occupations” so were under no obligation to go to war. Though go to war they did.

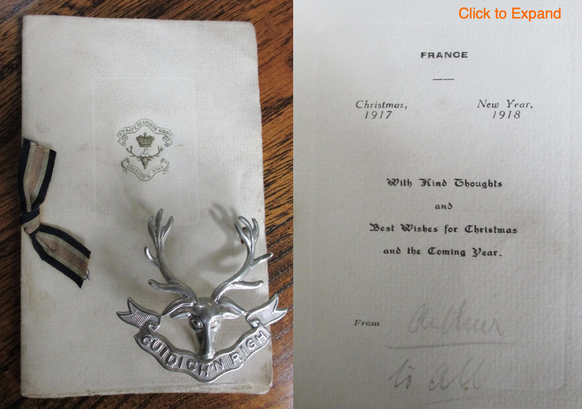

Because a considerable number of World War One service records were destroyed during World War Two, it is impossible to ascertain exactly when John and Arthur enlisted. However, the evidence available confirms that it was certainly prior to March 1918 and a Christmas card that Arthur posted to his sisters in Gildersome confirms that he was in France by December 1917. After their enlistment, John and Arthur would have spent ten week’s basic training at the 4th Seaforth Highlanders Reserve Training Battalion based at Ripon. On completion of which, and following a brief period of home leave, they will have embarked for France and life on the front line with the Seaforth Highlanders.

Because a considerable number of World War One service records were destroyed during World War Two, it is impossible to ascertain exactly when John and Arthur enlisted. However, the evidence available confirms that it was certainly prior to March 1918 and a Christmas card that Arthur posted to his sisters in Gildersome confirms that he was in France by December 1917. After their enlistment, John and Arthur would have spent ten week’s basic training at the 4th Seaforth Highlanders Reserve Training Battalion based at Ripon. On completion of which, and following a brief period of home leave, they will have embarked for France and life on the front line with the Seaforth Highlanders.

Commenting on his initial impressions of the replacement troops posted to the battalion in February 1918, Lt Col M.M. Haldane stated that ‘the appearance of the Battalion had changed greatly, for most of the new drafts were undersized men. So much was this the case that, on taking over the trenches, it became necessary to build up the fire steps, whereas in the old days they had to be lowered.’(1) Though I am unable to speak for John Hughes, the Arthur I remember would have been nearer to five foot than six (height was of little advantage in a two foot coal seam), so the idea of having to heighten the firing steps certainly has a ring of authenticity in Arthur’s case. This was perhaps symptomatic of a Battalion that had already depleted its traditional recruiting district of Ross and Cromarty and was now enlisting men in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Gaelic-speaking farm hands and crofters being replaced by Broad Yorkshire-speaking mill hands and colliers.

A typical Fire Step (Google)

A typical Fire Step (Google)

Having celebrated Christmas on the front line, John and Arthur unluckily found themselves at the very point at which Ludendorff intended to focus his last ditch attempt to end the war before the impending deployment of the newly arrived American forces was able to swing the balance in favour of the allies. With the war on the Eastern Front all but concluded, the Germans were able to concentrate a massive offensive in the West in what was to become the second battle of the Somme. It was within this context that Lance Corporal John Hughes and Private Arthur Taylor would become “Kriegsgefangenen.” (Prisoners of War)

On the 21st of March 1918, when the Germans launched their major offensive, 4th Seaforth took up positions on the road connecting Doignies and Hermies. Number 1 company, of which John and Arthur were part, was deployed in an advanced position. (2) The attack began at 7.15 on March 23rd and by 10 am number 1 company’s officers had been killed and the positions were being overrun. A contemporary newspaper account describes how the first shock of the enemy’s attack had fallen upon a company of Seaforths. Although heavily outnumbered, the Highlanders had stood firm. According to the report, it was only when their ammunition was gone and the enemy had deployed ”liquid fire” that the Seaforths were forced to leave their positions. However, instead of surrendering, the “Highland heroes” continued to engage the enemy with their bayonets, a few survivors managing to fight their way back through the “Hun positions” and join their comrades.(3)

On the 21st of March 1918, when the Germans launched their major offensive, 4th Seaforth took up positions on the road connecting Doignies and Hermies. Number 1 company, of which John and Arthur were part, was deployed in an advanced position. (2) The attack began at 7.15 on March 23rd and by 10 am number 1 company’s officers had been killed and the positions were being overrun. A contemporary newspaper account describes how the first shock of the enemy’s attack had fallen upon a company of Seaforths. Although heavily outnumbered, the Highlanders had stood firm. According to the report, it was only when their ammunition was gone and the enemy had deployed ”liquid fire” that the Seaforths were forced to leave their positions. However, instead of surrendering, the “Highland heroes” continued to engage the enemy with their bayonets, a few survivors managing to fight their way back through the “Hun positions” and join their comrades.(3)

The Battalion History presents a not quite so florid but no less dramatic account. It concludes by relating how ‘a sacrifice had been made to save [the] division, and the victims of the War God were the 4th Seaforth Highlanders.’(4) The Battalion War Diary, however, written as the battle was taking place, presents a more straightforward account: ‘enemy in overwhelming numbers all around us … about 3pm enemy entered our trench … it was decided to withdraw to supporting troops.’(5) On the 26th of March the Battalion War Diary’s summary of the engagement lists 32 men killed, 134 men wounded, 24 men wounded and missing, and 207 men missing.(6) John Hughes and Arthur Taylor were among the latter.

By some freak of coincidence, just as John and Arthur were being marched off into captivity, Arthur’s elder brother, Sim, had already spent two nights in the “cage.” Private Sim Taylor of the Machine Gun Corps had been taken prisoner less than 5 miles away at Bullecourt. Fortuitously, a local newspaper article printed in December 1918 presents a first hand account of Sim’s captivity and his experiences as a Kriegsgefangener:

By some freak of coincidence, just as John and Arthur were being marched off into captivity, Arthur’s elder brother, Sim, had already spent two nights in the “cage.” Private Sim Taylor of the Machine Gun Corps had been taken prisoner less than 5 miles away at Bullecourt. Fortuitously, a local newspaper article printed in December 1918 presents a first hand account of Sim’s captivity and his experiences as a Kriegsgefangener:

Pte Sim Taylor, of the Machine Gun Corps, 178th Brigade, who has arrived at his home in St Mary’s Square, Morley, after being a prisoner of war in Germany is a son of the late Mr and Mrs Charles Taylor of Gildersome, and was a filler at the Albion Mills, Morley (Messrs R and J Horsfall’s Ltd) when he joined up on the 25th November, 1914. He had been in France about a year when the Germans began their big offensive on the 21st March [1918]. ‘There were twelve of us with two machine guns at an isolated position near Bullecourt on the morning of that day,’ he says ‘and when the Germans came up in dense masses, about eight o’clock we realised that we were up against great odds. We kept them off a few hours during which they killed two of our men and wounded five others. They blew up our guns, smashing them to pieces. I and the other four who had not been hit began to fear the worst, but it seems we were up against a fairly decent lot of Germans. The first question they asked was ‘where are the Americans?’ There were no Americans near. They sent us five to their lines and we were collected among about 2,000 of our men in a big ‘cage’ where we spent three days and nights without anything to eat. Then we were sent on a two day’s march to Marchennes in Northern France and whenever the civilian population offered us food the Germans would knock it out of their hands. After spending a couple of days at Marchennes we were taken to the railhead and put on trucks in which we were kept just 48 hours with nothing more to eat than an ordinary slice of bread each. Finally, we landed at Munster, in Germany. At that place there happened to be a war loan campaign at the time, and they made use of us as an advertisement, marching us round the town to make the people believe, no doubt that they had got the whole of the British Army. The crowds were well conducted, however, and did not molest us in any way. We spent three weeks at Munster and the food was fairly good and plentiful, such as it was. We were afterwards selected in batches of 30 or 40 and put to different kinds of work. I was sent to a place about seven miles from Essen and was employed at the coke ovens and others were sent to work in the coal mine. Here the food was boiled cabbage and water every time and if we wanted any salt we had to buy it at 3d per lb. They paid us one mark a day, which we spent at their canteen, so they got it back again. Cigarettes cost two and a half pence each, so that a mark did not go very far. I may say that there was no soap in the country and tea was 36s per lb. We had coffee made from burnt barley, and when we refused to work after the armistice was signed they said ‘then no work, no more coffee.’ We were offered eight marks a day if we would continue working and they said that if we did not work they would have to stop the works, but we said that 80 marks a day would not keep us there. Then they got rid of us as quickly as possible, sending us into Holland. Most of our men had neither shirts nor socks, and many of them had only one boot or clog on their feet. In Holland we had a great reception, and were supplied with new uniforms, underclothing, boots and socks. After staying in Holland two days we sailed from Rotterdam for Hull and had quite a good reception from the ships, all of which sounded their sirens and hooters. Pte Taylor says that whilst working near Essen they could see our airmen bomb Essen and Cologne. He had no complaints except with regard to the food, and he says that whenever they complained on this score they were told that there was not sufficient food in Germany because of the British blockade.(7)

Sim’s account of his captivity, it seems to me, is remarkably understated and contrasts starkly with depositions given to the War Office by ex prisoners who drew attention to the, often brutal, mistreatment meted out by their captors. From a perspective now distanced by more than a hundred years, it is difficult to understand how men forced into hard labour with nothing to sustain them other than a daily ration of boiled cabbage, some without shirts or socks, and hobbling around on a single boot would be able to overlook these deprivations with such equanimity.

Sim’s understatement is perhaps brought into sharper focus when he goes on to talk about the location in which he was put to work. He states that this was near Essen at ‘the coke ovens’ and that others had been sent to ‘the coal mine.’ Intriguingly, in his discussion of working conditions for PoWs in Germany, John Lewis-Stemple talks about British prisoners being forced to work at what he describes as the ‘infamous Auguste Victoria or K-47 coal mine,’ which was then Europe’s largest colliery. He also talks about a coking plant that was part of the same operation. Lewis-Stemple’s account draws on a statement made by a PoW describing his work at the coking plant:

Sim’s understatement is perhaps brought into sharper focus when he goes on to talk about the location in which he was put to work. He states that this was near Essen at ‘the coke ovens’ and that others had been sent to ‘the coal mine.’ Intriguingly, in his discussion of working conditions for PoWs in Germany, John Lewis-Stemple talks about British prisoners being forced to work at what he describes as the ‘infamous Auguste Victoria or K-47 coal mine,’ which was then Europe’s largest colliery. He also talks about a coking plant that was part of the same operation. Lewis-Stemple’s account draws on a statement made by a PoW describing his work at the coking plant:

‘The men had to do shifts of from half an hour to an hour unless they dropped out before, which they frequently did. The heat was intense and I have seen men with their feet and faces scorched and blistered … The work was shifting 32 tons of coke in 12 hours … and the men simply had to work until it was done.’(8)

Seaforth Highlanders cap badge, along with the regimental Christmas card that Arthur sent to his sisters in December 1917.

Seaforth Highlanders cap badge, along with the regimental Christmas card that Arthur sent to his sisters in December 1917.

This account is markedly different in tone from that provided by Sim. The pit and coking plant described here was situated near Marl. Marl lies some 30 miles west of Munster and 18 miles north of Essen (a good vantage point from which to watch the air raids on that city). While it is impossible to state with certainty that Sim was indeed working at the same Auguste Victoria coking plant described above, the circumstantial evidence suggests a very strong possibility that he could have been. If so, the equanimity of Sim’s description of his time in captivity is all the more remarkable.

With these reservations in mind we might assume that John and Arthur’s experience of captivity would be broadly similar to that recorded in Sim’s interview above. While Sim was registered as a PoW at Munster, John and Arthur had to make a much longer journey to the prison camp at Parchim, some 40km from the Baltic coast. After registration they will also have been allocated to an Arbeitskommando and put to work, possibly at some distance from the main camp. The working conditions varied from place to place, but were generally harsh. Because they had become a critical component of the economic structure of the Kaiser’s Germany, Kriegsgefangenen were fed as little as possible and made to work as hard as possible. Unsurprisingly, the harsh conditions and lack of nutrition often resulted in illness, and illness often resulted in death. During the final year of the war, the death rate of British other ranks on the battlefield ran at 4%, for British prisoners of war the overall death rate was 10.3%.(9) Statistically, it appears that a man was safer in the trenches than in captivity.

After the Armistice was signed in November 1918, thousands of Kriegsgefangenen were repatriated. Sim Taylor, as we have seen above, journeyed through Holland and was shipped to Hull. Surviving records reveal that his brother Arthur landed at Dover on the 30th of November 1918. Sadly, John Hughes never made it home; his death was recorded by the Red Cross on the 23rd of July 1918. He died in a prison hospital facility at Limburg and he was eventually buried at Tournai. Cause of death is listed as pleurisy (Rippenfellentaundung).(10) Under normal circumstances, pleurisy manifests as a complication to a pre-existing viral condition such as influenza, with the very young and very old being most susceptible. That John Hughes contracted pleurisy at the age of 25 suggests that his resistance to the disease had been compromised. When Arthur Taylor arrived back at Gildersome he weighed less than eight stone, a legacy of his experience as a Kriegsgefangener. That level of weight loss is clearly indicative of poor levels of nutrition. It is not unreasonable to speculate, then, that the conditions of John Hughes’s captivity had been a contributing factor to his death.

A vague memory of an old photograph of a soldier in a kilt has eventually contrived to uncover the forgotten narrative of two friends who went to war. It has also revealed something of the desperate hardships endured by prisoners of war (Kriegsgefangenen) during World War One. Held captive in a country that was, by this time, barely able to feed its own population, it is perhaps inevitable that the Kriegsgefangenen would suffer considerable deprivation. The extent of that deprivation is realised in the death of John Hughes, just one of over 12,000 British PoWs who died in captivity, 3,000 of which are estimated to have died of starvation. (11)

With these reservations in mind we might assume that John and Arthur’s experience of captivity would be broadly similar to that recorded in Sim’s interview above. While Sim was registered as a PoW at Munster, John and Arthur had to make a much longer journey to the prison camp at Parchim, some 40km from the Baltic coast. After registration they will also have been allocated to an Arbeitskommando and put to work, possibly at some distance from the main camp. The working conditions varied from place to place, but were generally harsh. Because they had become a critical component of the economic structure of the Kaiser’s Germany, Kriegsgefangenen were fed as little as possible and made to work as hard as possible. Unsurprisingly, the harsh conditions and lack of nutrition often resulted in illness, and illness often resulted in death. During the final year of the war, the death rate of British other ranks on the battlefield ran at 4%, for British prisoners of war the overall death rate was 10.3%.(9) Statistically, it appears that a man was safer in the trenches than in captivity.

After the Armistice was signed in November 1918, thousands of Kriegsgefangenen were repatriated. Sim Taylor, as we have seen above, journeyed through Holland and was shipped to Hull. Surviving records reveal that his brother Arthur landed at Dover on the 30th of November 1918. Sadly, John Hughes never made it home; his death was recorded by the Red Cross on the 23rd of July 1918. He died in a prison hospital facility at Limburg and he was eventually buried at Tournai. Cause of death is listed as pleurisy (Rippenfellentaundung).(10) Under normal circumstances, pleurisy manifests as a complication to a pre-existing viral condition such as influenza, with the very young and very old being most susceptible. That John Hughes contracted pleurisy at the age of 25 suggests that his resistance to the disease had been compromised. When Arthur Taylor arrived back at Gildersome he weighed less than eight stone, a legacy of his experience as a Kriegsgefangener. That level of weight loss is clearly indicative of poor levels of nutrition. It is not unreasonable to speculate, then, that the conditions of John Hughes’s captivity had been a contributing factor to his death.

A vague memory of an old photograph of a soldier in a kilt has eventually contrived to uncover the forgotten narrative of two friends who went to war. It has also revealed something of the desperate hardships endured by prisoners of war (Kriegsgefangenen) during World War One. Held captive in a country that was, by this time, barely able to feed its own population, it is perhaps inevitable that the Kriegsgefangenen would suffer considerable deprivation. The extent of that deprivation is realised in the death of John Hughes, just one of over 12,000 British PoWs who died in captivity, 3,000 of which are estimated to have died of starvation. (11)

World War One recruiting poster: an image that might have persuaded Arthur and his mates to join the Seaforths. It looks like a lot of fun!

World War One recruiting poster: an image that might have persuaded Arthur and his mates to join the Seaforths. It looks like a lot of fun!

Postscript:

John Hughes and the Taylor brothers were not the only Gildersome soldiers who became Kriegsgefangenen during the spring of 1918. Pte David Henry Ward of the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards was taken prisoner at Mervil on April 13th and was registered as a prisoner of war at Friedrichsfeld. Private Ward was repatriated to Hull aboard the SS Archangel on 22nd November, 1918. His address was listed as 15 Birchfield Place, Gildersome. In addition, Pte Walter Abbott, of the York and Lancaster regiment, was captured at Estaires on April 12th and was also registered at Friedrichsfeld PoW camp. Walter was repatriated to Hull on 23rd November 1918. His address was listed as the Junction Inn, Gildersome, just a matter of yards from the cottage that Arthur Taylor shared with his sisters. Walter succeeded his father to become landlord of the Junction from 1930 until 1957.

Along with John Hughes, two other Gildersome men are known to have died in captivity. Percy Scargill of the West Yorkshire Regiment was reported missing on 27th March 1918. German records reveal that he was captured at Hamlincourt and registered at Parchim PoW camp. He was later transferred to the camp at Friedrichsfeld. Percy died on 12th October 1918; the cause of death is unknown. The cause of Fred Thackray’s death, on the other hand, is known. Pte Fred Thackray of the Durham Light Infantry was listed as missing on 26th May 1918. The only evidence of his captivity states that Fred died on 24th July 1918. Cause of death: “Kopfschuss.” Fred was shot in the head. Captured men were often put to work close to the front line. Undertaking tasks such as repairing trenches and relaying communication cables in range of Allied snipers and artillery was especially dangerous (it was also a breach of the Geneva Convention). Because there is no record of him being registered as a PoW it is possible that Fred was killed while working close to the front line and exposed to what is now euphemistically termed “friendly fire.”

Subsequent research has also revealed that John Hughes and Arthur Taylor were not the only local men who enlisted with the Seaforth Highlanders. A regimental document reveals that John Hughes (201459), Arthur Taylor (201550), James William Goor (201551) and James Byrom (201552) were awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal while serving with the Seaforth Highlanders. The sequencing of their serial numbers makes it almost certain that they enlisted at the same time. The 1911 census shows that James Goor was living in nearby Adwalton, though by 1939 he is listed as living in Vicarage Avenue. James Byrom was a Birstall man. All four men were colliers and could well have worked at the same colliery.

John Hughes and the Taylor brothers were not the only Gildersome soldiers who became Kriegsgefangenen during the spring of 1918. Pte David Henry Ward of the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards was taken prisoner at Mervil on April 13th and was registered as a prisoner of war at Friedrichsfeld. Private Ward was repatriated to Hull aboard the SS Archangel on 22nd November, 1918. His address was listed as 15 Birchfield Place, Gildersome. In addition, Pte Walter Abbott, of the York and Lancaster regiment, was captured at Estaires on April 12th and was also registered at Friedrichsfeld PoW camp. Walter was repatriated to Hull on 23rd November 1918. His address was listed as the Junction Inn, Gildersome, just a matter of yards from the cottage that Arthur Taylor shared with his sisters. Walter succeeded his father to become landlord of the Junction from 1930 until 1957.

Along with John Hughes, two other Gildersome men are known to have died in captivity. Percy Scargill of the West Yorkshire Regiment was reported missing on 27th March 1918. German records reveal that he was captured at Hamlincourt and registered at Parchim PoW camp. He was later transferred to the camp at Friedrichsfeld. Percy died on 12th October 1918; the cause of death is unknown. The cause of Fred Thackray’s death, on the other hand, is known. Pte Fred Thackray of the Durham Light Infantry was listed as missing on 26th May 1918. The only evidence of his captivity states that Fred died on 24th July 1918. Cause of death: “Kopfschuss.” Fred was shot in the head. Captured men were often put to work close to the front line. Undertaking tasks such as repairing trenches and relaying communication cables in range of Allied snipers and artillery was especially dangerous (it was also a breach of the Geneva Convention). Because there is no record of him being registered as a PoW it is possible that Fred was killed while working close to the front line and exposed to what is now euphemistically termed “friendly fire.”

Subsequent research has also revealed that John Hughes and Arthur Taylor were not the only local men who enlisted with the Seaforth Highlanders. A regimental document reveals that John Hughes (201459), Arthur Taylor (201550), James William Goor (201551) and James Byrom (201552) were awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal while serving with the Seaforth Highlanders. The sequencing of their serial numbers makes it almost certain that they enlisted at the same time. The 1911 census shows that James Goor was living in nearby Adwalton, though by 1939 he is listed as living in Vicarage Avenue. James Byrom was a Birstall man. All four men were colliers and could well have worked at the same colliery.

Notes:

1. Haldane MM (1927) A History of the Fourth Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders with some Account of the Military Annals of Ross the Fencibles the Volunteers and of the Home Defence Reserve Battalions 1914-1919. London: HF&G Witherby. p. 264.

2. Ibid. p 270.

3. Daily Record, 28th March 1918.

4. Haldane MM (1927) A History of the Fourth Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders with some Account of the Military Annals of Ross the Fencibles the Volunteers and of the Home Defence Reserve Battalions 1914-1919. London: HF&G Witherby. p. 273.

5. National Archives. WO-95-2888-1918.

6. Ibid

7. Morley Observer, 27th December 1918.

8. Lewis-Stempel S, 2014, The War Behind the Wire: the Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-18. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

9. Ibid.

10. National Archives.

11. Lewis-Stempel S, 2014, The War Behind the Wire: the Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-18. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. P. 94.

1. Haldane MM (1927) A History of the Fourth Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders with some Account of the Military Annals of Ross the Fencibles the Volunteers and of the Home Defence Reserve Battalions 1914-1919. London: HF&G Witherby. p. 264.

2. Ibid. p 270.

3. Daily Record, 28th March 1918.

4. Haldane MM (1927) A History of the Fourth Battalion The Seaforth Highlanders with some Account of the Military Annals of Ross the Fencibles the Volunteers and of the Home Defence Reserve Battalions 1914-1919. London: HF&G Witherby. p. 273.

5. National Archives. WO-95-2888-1918.

6. Ibid

7. Morley Observer, 27th December 1918.

8. Lewis-Stempel S, 2014, The War Behind the Wire: the Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-18. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

9. Ibid.

10. National Archives.

11. Lewis-Stempel S, 2014, The War Behind the Wire: the Life, Death and Glory of British Prisoners of War, 1914-18. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. P. 94.